Policy Center for the New South

Seeking Alpha

TheStreet.com

The pandemic has hit Latin America hard, and its economic recovery has been slower than in other regions. In addition to the legacy of higher public indebtedness, the pandemic left scars on the labor market and the human capital formation of future workers.

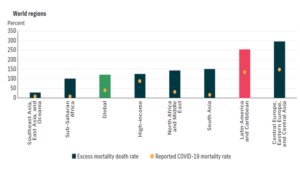

The COVID-19 crisis has receded in Latin America but has left a significant toll. Reported deaths from the pandemic are currently low and converging to global levels. The average excess mortality during the pandemic was among the highest in the world: double the worldwide average and second only to Central Europe, Eastern Europe, and Central Asia, according to the latest World Bank’s Latin America and the Caribbean Economic Review (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020–21 (percent)

Source: World Bank (2022).

Economic growth is not expected to exceed the pace of the 2010s. In most countries, employment and GDP have already returned to pre-pandemic levels. On the other hand, as the World Bank report states, growth forecasts for the next few years suggest they be “resiliently mediocre”.

The post-pandemic recovery partially reversed the 2020-21 poverty increase. But neither the permanent losses of gross domestic product (GDP) during the pandemic will be recovered, nor have the long-term scars on health, education, and future inequality been erased.

The Russian invasion and the war in Ukraine also had an economic impact on the region, mainly through the shock of commodity prices and consequent increases in domestic inflation rates. While commodity exporters (importers) had positive (adverse) effects on their GDPs, through terms of trade, they all had to face higher food and energy inflation, affecting mainly the bottom of the income pyramid income, given the weight of these items in their consumption basket.

This year’s growth rate forecasts for the region have steadily increased since January – in contrast to downgrades for the rest of the world because of the war in Ukraine. The GDPs of net food and fuel importers, such as the Caribbean and Central American countries, were negatively affected. Rising prices for these goods have also affected households across the region. On the other hand, the general increase in commodity prices has been a boon in terms of GDP for regional exporters such as Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru.

For commodities as a group, 2022 has been a very volatile year. After rising dramatically in the first half, prices retreated in the third quarter, reflecting China’s slowdown growth and the appreciation of the US dollar. A shock followed the supply shock arising from the war in Ukraine in declining demand.

According to the IMF’s World Economic Outlook released two weeks ago, tailwinds from commodity prices should change course. In the case of oil prices, futures markets point to a fall in the coming years after rising 41% in 2022. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has raised base metal prices, but they are expected to end 2022 at levels 5.5 % lower on average and to decline by a further 12.0% in 2023. The IMF report predicts that precious metals prices will fall more moderately: 0.9% in 2022 and an additional 0.6% in 2023.

Food commodity prices, which also surged after Russia invaded Ukraine, fell to pre-war levels this summer, ending a two-year rally. Not before adding 5 percentage points to the country’s average food price inflation in 2021, plus an estimate of 6 percentage points in 2022 and 2 percentage points in 2023.

The asymmetric effects of higher commodity prices on the region’s population, mainly undermining the purchasing power of the bottom of the pyramid, have been – to varying degrees – accompanied by social transfer policies and other types of support. The absence of readily available fiscal space for such use has been a constraint.

The increased frequency and coverage of adverse weather events, likely already reflecting climate change, has also been another food and energy price shock source. In recent years, more frequent floods and droughts have affected food and energy supplies in China, India, Europe, the US, Africa, and Latin America. Climate change, a plague (pandemic), war, and the higher risks of hunger constituted a “perfect storm”.

In addition to the effects of these three shocks, a fourth shock has come with the tightening of global financial conditions. Central banks in advanced economies have met high global inflation with tighter monetary policies.

Growth dynamics surprised most of the region positively, favored by the return of the services and employment sectors to pre-pandemic levels, as well as external conditions that remained favorable until recently – including still high commodity prices, still strong external demand, and remittances, in addition to the return of tourism. These were the explanatory factors behind the upward revisions to growth forecasts from January onwards.

But tightening global financial conditions are pushing in the opposite direction now. The availability and costs of domestic finance have become less friendly as the region’s major central banks have raised their interest rates to control domestic inflation. Capital inflows decreased, and external borrowing costs increased due to lower risk appetite on the part of investors.

The region is generally more resilient to an ongoing monetary-financial shock like this than in previous times. Banking systems are healthier, and public balance sheets are usually not as fragile as at times in the past. The cushion in foreign exchange reserves also makes a difference in many cases.

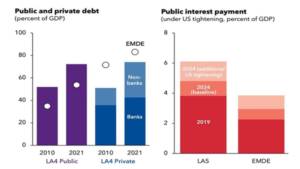

However, corporate debt outside the banking system is a point that deserves attention. Higher domestic interest rates will also tighten conditions for rolling over public debt (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – High Debt

Source: Acosta-Ormaechea et al (2022).

Note: LA4 = Brazil, Chile, Colombia, and Mexico; LA5 = LA4 plus Peru; EMDE = Emerging Market and Developing Economies.

After the upward surprises in GDP growth in 2022, the expected performance for next year is weaker. While the IMF and World Bank expect the average GDP growth rate to reach 3.5% and 3% in 2022, their forecasts go down to 1.7% and 1.6% in 2023.

Latin America’s recovery after the perfect storm should not be limited to a simple return to pre-pandemic “mediocre” levels of output growth. Investments in green infrastructure, exploring areas of digital connectivity opened by the pandemic, and improving the business environment and education can lead to more resilient, inclusive, and dynamic growth patterns.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil.

This Post Has 2 Comments

Fine study

Thanks

Comments are closed.