Financial Times, 22 December 2016 By OTAVIANO CANUTO

In recent years Brazil has experienced significant depreciation of its nominal exchange rate. Compared to the 2013 average, the Real lost 38 percent of its value vis-à-vis the USD in 2016. At its weakest, in January 2016, it dipped as low as 47 percent. A year ago, that depreciation was approached here as a silver lining for Brazil in its ongoing recession. However, Brazil’s recent GDP data (particularly the second quarter of 2016) show a negative contribution of net exports to growth.

In order to understand why, one must reckon that the nominal Real to US Dollar exchange rate does not determine the relative competitiveness of Brazilian producers, and this is better gauged by the Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER). The REER corrects for two important factors. First, it takes into account movements of all the nominal exchange rates with a country’s trading partners. Second, the REER corrects for changes in domestic prices in the various economies.

An alternative way of measuring the real exchange rate is the price level of tradable goods vis-à-vis that of non-tradables and services in the economy. If tradable goods become relatively more pricy, this amounts to a real depreciation, incentivizing the production of tradable goods and dis-incentivizing their domestic consumption. Both should result in higher net exports. This second measure of the real exchange rate can be estimated empirically by comparing the relative change in domestic price indices for different categories of goods.

So what has really happened to the Brazilian Real?

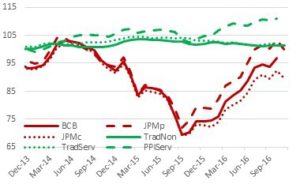

The Chart depicts six different measures for the Brazilian real exchange rate to assess how much real depreciation the currency has experienced in recent years. Three are published REER indices (that of the Brazilian Central Bank, JP Morgan’s REER index using consumer prices and JP Morgan’s REER index using producer prices). The other three are calculated using Brazilian domestic prices: the tradable relative to the non-tradable category in Brazil’s broad consumer price index (IPCA); the tradable category relative to the services category in the same index, and finally the producer price index (IPP), which contains mostly raw materials and other tradable non-final goods, relative to the services index.

Our results are twofold: First, REER indices using exchange rates are much more volatile than domestic price-based indices. Second, according to all six indices the Brazilian Real has depreciated little or not at all relative to its 2013 level.

The REER indices broadly follow the BRL/USD exchange rate, even though at a dampened level, given the weight of other currencies in the index and the inflation differential between Brazil and most trading partners. According to REER measures, the Real did experience real depreciation of up to 30 percent by the end of 2015 but has recovered most of this in 2016 as the currency strengthened vis-à-vis most partners, not just the Dollar but also other currencies such as the Renminbi and the Euro which have weakened this year relative to the Dollar.

The domestic prices-based indices are much less volatile but seem to contain a long-term trend towards appreciation, as non-tradables and especially services become relatively more expensive over time. This is of course in line with the structural transformation of the Brazilian economy, which has become much more services-based in recent decades. Since 2013, these real exchange rate measures are essentially stable, possibly ending the appreciating trend, even though the measure using producer prices shows strong appreciation in 2016 (probably related to weak commodity prices and nominal appreciation).

The low volatility in price-based measures speaks to the relative stability in relative prices compared to exchange rates. In Brazil, it also speaks to the low pass-through of exchange rate depreciation to prices (even those of tradable goods) which is related to the exceptionally low share of trade in GDP. It also speaks to stubborn services inflation in Brazil, which has just fallen below 7 percent after two years of severe recession. Sources: IBGE, BCB, JP Morgan, Haver Analytics, authors’ calculation. All reindexed to 2013 average = 100; a falling index represents depreciation of the Brazilian currency.

Brazil REER and Tradables to Non-tradables (2013 = 100) and BRL/USD (RHS, inverted), since 2002 |

| Six Real Exchange Rates for Brazil over the last 3 years (2013 = 100)

|

Sources: IBGE, BCB, JP Morgan, Haver Analytics, authors’ calculation. All reindexed to 2013 average = 100; a falling index represents depreciation of the Brazilian currency.

What does this mean for Brazil’s real economy?

The Brazilian Real is probably still – or again – overvalued, since it has not depreciated much in real terms two years after the country entered into recession. This assessment appears to be shared by the IMF in its July External Sector Report, according to which the Brazilian Real was overvalued during 2012-2015.

The reversal of the Real’s depreciation over the course of 2016 is likely to have resulted in less support for growth from net exports than the nominal level of the BRL/USD rate might suggest. Hope for a trade-based recovery was premature, given that relative prices in the domestic economy did not change significantly.

Otaviano Canuto is an executive director at the board of the World Bank. All opinions expressed here are his own and do not represent those of the World Bank or of those governments he represents at its Board.