First appeared at Policy Center for the New South

Also at Seeking Alpha and TheStreet.com

In addition to the human toll and damage to the local economy, the war in Ukraine is bringing substantial financial, commodity price, and supply chain shocks to the global economy.

The sanctions established against the Central Bank of the Russian Federation have already restricted its access to international reserves and made it harder to back its currency and financial system. International sanctions on Russia’s banking system and the exclusion of some banks from SWIFT have significantly disrupted Russia’s ability to receive payments for exports, pay for imports and engage in cross-border financial transactions. Sanctions are already having a significant impact on the Russian financial system and its economy. They will also bring some spillovers to other economies.

Price shocks will have a global impact. Energy and commodity prices—including wheat and other grains—have risen, intensifying inflationary pressures from supply chain disruptions and the recovery from the pandemic. As poor households spend a high proportion of income on food and fuel, they will be particularly hurt.

The war also brought a negative shock to both inflation and economic activity in many countries, amid already high inflationary pressures. Central banks were already facing a need to walk on a tightrope between curbing inflation and maintaining financial stability. The war in Ukraine has made such a rope thinner.

The push toward relative deglobalization received from the pandemic will get stronger (Canuto, 2022a). The war in Ukraine may become a turning point in the evolution of international payment systems. By the same token, geopolitics may also come to the fore with respect to access and usage of some key commodities.

The Weaponization of finance

The war will be devastating for Ukraine. The economic sanctions against Russia, in turn, announced by the United States and Europe following the military invasion of Ukraine are having a profound impact on the Russian economy while also having repercussions everywhere. As in a boxing match, the expectation is that blows to the opponent can knock them out, despite the exposure on the punching side.

The United States has applied some sectoral and limited economic sanctions against Russia since the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the military clashes in eastern Ukraine. Nothing comparable, however, to what was announced in the weekend after the entry of Russian troops into Ukraine.

Between February 22nd and 27th, we had announcements by the United States, the 27 members of the European Union and the G7 countries of freezing assets of large Russian banks, some Russian individuals, and controls on the export of technology products. Culminating with removing some Russian banks from the SWIFT system and banning transactions with the Central Bank of Russia.

SWIFT is a messaging network connecting banks worldwide that is considered a backbone of international finance. SWIFT is a consortium managed by employees of member banks, including the USA’s central banks, Europe, Belgium, England, and Japan. Based in Belgium, it is a consortium linking more than 11,000 financial institutions in more than 200 countries and territories, operating as a link that makes international payments possible. To give you an idea, in 2021, the system recorded an average of 42 million messages per day, including requests and confirmations of payments, negotiations and currency exchanges. Over 1% of these messages are believed to have involved Russian payments.

Would there be any alternatives for Russians to transfer and normalize their operations outside of SWIFT? Russia has an alternative network, the System for Transfer of Financial Messages, but it cannot be a replacement. By the end of 2020, the system only included 400 participants from 23 countries. Also, China’s Cross-Border Interbank Payment System could not be a perfect replacement, at least soon, as it does not incorporate SWIFT members.

The banning of transactions with the Russian central bank is the major jab. Besides being the lender of last resort to commercial banks in its domestic currency, it is also the lender of last resort in foreign exchange. Foreign exchange reserves matter not only for avoiding exchange rate crises but also because they prevent runs on banks and make possible payments of the foreign debt of state and private corporations. And there has been an increasing digitalization of international finance.

The bulk of countries’ foreign reserves no longer is made of not physical certificates of government bonds or stocks of cash in dollars, euros, pounds, and yen. They are now electronic book entries on the computer ledgers of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the European Central Bank, European national central banks, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, and Swiss commercial banks.

Digitalization creates a wedge between ownership and control of foreign exchange reserves, as western issuers and computerized holders of these assets control access to assets despite Russia’s owning them. The closure of Russia’s access to these assets, freezing them, and prohibiting all private transactions with the Russian central bank suddenly halted any possible sale of securities and cash withdrawal from western banks. As well summarized by Michael Bernstam (Financial Times, March 22):

“In less than one day, the Russian central bank and Russians lost access to 60 per cent of .X.F.X. reserves, $388bn out of a total $643bn. They lost access to entire arrays of assets: securities and deposits in western central banks ($285bn) and in western commercial banks and brokerages ($103bn). The Russian central bank is left with $135bn worth of gold in its vaults, $84bn of Chinese securities denominated in renminbi, a $5bn position in the IMF and a residual $30bn in actual cash, dollars and euros. (These are my calculations from central bank data).

With 60 per cent of .X.F.X. reserves out of commission, Russia has to rely on the remaining 40 per cent, but there is no freedom to operate there either. The central bank cannot sell gold for dollars and euros because all transactions with it are prohibited and foreign bankers and dealers do not want to invite western wrath. The IMF reserve position is untouchable. Some $84bn in Chinese securities could, hypothetically, have been sold back to China, with a discount, to be paid in dollars, cut to $50bn, but China’s state banks have already refused financial deals with Russia. Which leaves only $30bn in cash — too little to prevent financial and economic ruin.”

Sanctions are already having a significant impact on the Russian financial system and its economy. The Ruble’s value collapsed, losing over 30% of its value in the following week. The Central Bank of Russia was led to put interest rates up high to limit the transmission of currency devaluation to inflation. The bank run by the population began over the weekend through ATMs. Restrictive capital controls and bank holidays have become are the new normal.

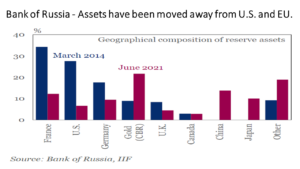

Despite the strategy of reducing exposure since the beginning of sanctions in 2014, via geographic relocation of reserves and acquisition of gold, and changing currencies in commercial transactions – a kind of “de-dollarization” – Russia has not become invulnerable and the impact will be significant – Figure 1. The GDP contraction will not be light, given the tightening of financial conditions accompanying ultra-high interest rates and banks without access to foreign currency.

Figure 1

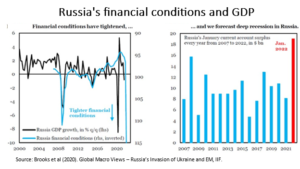

Figure 2 shows the impact on Russia’s financial conditions – as measured by a composite of the falling Ruble, the stock market collapse, rising bond yields plus credit spreads – and on GDP. JPMorgan is forecasting a GDP downfall by 35% in the year’s second quarter. A government debt default in March is expected.

Figure 2

The sanctions were tentatively designed to minimize their effect on Russian gas imports into Europe. The sanctions announced on February 26 were more limited in scope than the broader targeting advocated by other countries to win Germany’s support. They do not impact ‘Russia’s energy sector transactions, and the .U.E.U. has not sanctioned some of Russia’s largest banks. Consequently, euro- and dollar-denominated payments can continue to flow through Russia’s energy exports.

.S.Europe and the U.S. seem to be reluctant to implement such measures. That could change with additional rounds of sanctions, and Russian firms are widely disconnected from SWIFT. And even if Russia’s banking sector is primarily unplugged from SWIFT, Beijing and some in Europe may use alternative payments channels to keep euro and renminbi payments flowing to Russia; already, more than half of Russian exports are exports are not dollar denominated.

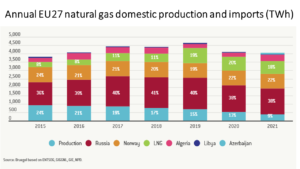

The Bruegel Institute, a Brussels-based think tank, tackles scenarios of how Europe would suffer from a halt in the flow of Russian gas (Figure 3). Despite the self-inflicting pain, halting gas imports immediately would still be possible.

Figure 3

With some collateral damage

And outside Russia? Of course, the receiving side of payments – creditors, asset investors – will also be impacted. Russian defaults are practically inevitable. The consequences of that will only be extended if the devaluation of the corresponding assets leads to some contagion effect – for example, withdrawal of funds by investors in mutual funds forcing their managers to liquidate other assets in their portfolios to pay for the withdrawal of funds.

How about fears and risk aversion in financial markets? In fixed-income markets, the week after sanctions, U.S. government-bond yields started trading around 25 basis points lower than before the invasion. While half of this drop could be attributed to uncertainties generated by Russia’s invasion, the other half has been taken as due to a downward movement of expectations about the Fed’s speed of monetary tightening ahead. The Fed is expected to raise its basic rate only by 0.25% in March 15-16, rather than 0,5% as previously expected. Also, the number of expected interest rate hikes this year has declined to 5 instead of 7.

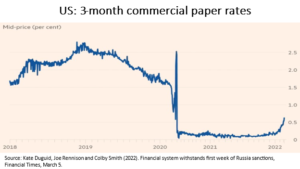

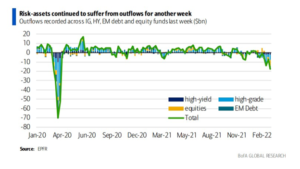

Levels of short-term borrowing stress have gone up. Figure 4 exhibits rates on three-month commercial papers, and there is nothing comparable so far to moments of crises in the past. The Federal Reserve facilities boosted during the pandemic to support foreign central banks have not been used. At least in the first week after sanctions on Russia, there has been no fear of illiquidity and “dash for cash”. It is worth noticing, on the other hand, an uptick on the exit from risk assets that had been in the course before the invasion and sanctions (Figure 5)

Figure 4

Figure 5

It is too early to make any definitive call – among other reasons because massive defaults in payments from Russia have not kicked in yet, with corresponding effects on chains of securities that depend on Russian assets. But one may acknowledge that there has been a big blow to the system of global payments. The precedent of targeting a major country’s foreign reserves tends to have long-term enduring impacts.

Most likely, China – and Russia – will accelerate any plans it may have on disconnecting from U.S.- and EU-led payments channels. Beijing is poised to search for boosting a China-led, renminbi-denominated payments channels across Asia—including in Russia—that are mainly out of reach of U.S. sanctions and less dependent on SWIFT.

Still on the sanctions on Russia, one relevant issue will be to define how and when sanctions would be reversed. To work effectively as a means of pressure, sanctions need to be integrated into a clear pathway indicating what Russia would have to do for sanctions to be lifted (Greene, 2022).

Commodity price shocks

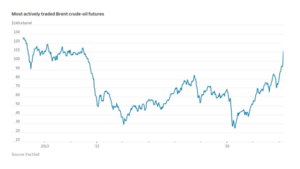

In the week after the invasion, commodity prices rose at a pace without precedent in the last 50 years. Oil prices rose to $120 a barrel, the highest level since 2012, while wheat prices climbed by almost 50%.

The sanctions package announced on February 26 was designed to spare oil and gas payments to Russia. However, with traders now afraid of the risks associated with dealing with any Russian counterparties, many have chosen not to purchase Russian oil this week, leading to a new rise in oil prices.

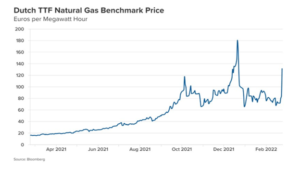

Through the rise in energy commodity prices – in addition to possible restrictions on the logistics of Russian products – the war in Ukraine will affect most economies in the rest of the world. Figure 6 displays the recent evolutions of the Dutch TTF natural gas price, and Figure 7 depicts the recent evolution of oil prices.

Figure 6

Figure 7

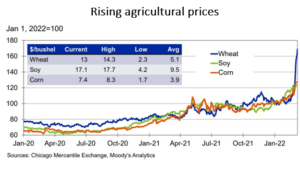

Furthermore, there is a statistically proven asymmetry: what happens in the subgroup of energy commodities affects the others, such as food and metals (Yang et al., 2021). Food prices have been going up (Figure 8).

Figure 8

A particular food commodity to feel the impact of the war will be wheat – which is particularly impactful in some regions, such as North Africa and the Middle East, as seen in Figure 8. Russia and Ukraine are sources of almost a third of the worldly traded wheat.

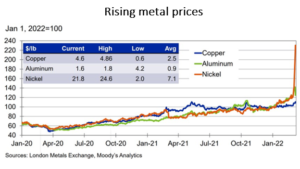

Russia is also a significant supplier of fertilizers, palladium, aluminum, and other products which may be affected by logistic “supply chain restrictions” provoked by military conflict, sanctions, and voluntary restrictions to trade. The aluminum and steel produced by Russia is used in a wide range of manufactured goods, from beverage cans to smartphones to cars. Ukraine and Russia are substantial sources of palladium and platinum, and both used to manufacture catalytic converters for the auto industry. Platinum, copper, and nickel are critical inputs for electric vehicles’ batteries. Ukraine is also the source of 50% of the world’s neon gas, which is used for lasers employed in manufacturing semiconductor chips – one may guess that the global semiconductor chip shortage is unlikely to end soon.

Belarus, a close Russian ally, is a great producer of potash, a key fertilizer input. Sanctions on the country will negatively affect its availability. Food commodity exporters may accrue a gain— if they do not depend on Belarusian potash — but importers that rely on buying essential food and fuel on international markets could face dire conditions.

Market prices (Figure 9) are reflecting a belief that a supply reduction for some time can be taken for granted time, and damage may already have been done to potential yields. Prices are reflecting a geopolitical risk premium. The impact of the war on commodities tends to stay for some time, even if it occasionally eases slightly.

Figure 9

Supply chain disruptions

Those supply shocks intermingle with the supply chain disruptions that have affected macroeconomic performance and inflation during the pandemic (Canuto, 2021a). Military conflicts are bound to bring additional challenges.

Transportation and logistics industries are being affected: flight cancellations, higher pressure on cargo capacity because of re-routings, closure of Ukrainian ports, the banishment of Russian ships from U.K. ports, and the suspension of Russian cargo bookings by the world’s most prominent shipping groups (Moody’s, 2022). Already long delivery times and shipping and producer costs are rising.

Furthermore, the military conflict and sanctions on Russia also impact the global supply of those commodities exported by Russia and Ukraine previously mentioned. Energy and commodities trade with Russia has not been sanctioned yet, but trade with Ukraine has paralyzed.

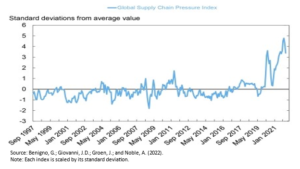

The supply chain disruptions were yet a significant challenge before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Figure 10 exhibits an index of global supply chain pressure developed by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York through February 2022, pointing to an easing since December 2021, even though remaining at historically high levels with numbers (Benigno et al., 2022). The next figures will likely bring index hikes.

Figure 10

Like in the case of finance, the war in Ukraine has raised attention to the way that many raw materials have the potential to be used as weapons of foreign policy — mainly if a new cold war develops that divides Russia, and potentially China, from the west. Geopolitics will bring commodities to its center. To some extent, this brings some echoes from the era of Imperialism.

Risks of Stagflation

In most advanced economies, inflationary acceleration has been taking place. Japan was an exception. Consumer price inflation ended 2021 at annualized rates of 6,7% in the U.S., 4.6% in the Euro area, 4.9% in U.K., and 5.1% as an average of developed economies.

This has already led monetary authorities to issue signs of shifting towards less accommodative policies. More gradually in the Euro area, while bets among analysts on the U.S. Federal Reserve’s future decisions even included, before the war in Ukraine, 6 or 7 increases in its base rates this year, perhaps including even the beginning of the shrinkage of the asset portfolio on its balance sheet – a “quantitative tightening (Q.T.)” following the end of “quantitative easing (Q.E.)”. A rise in March – 25 or 50 basis points – became taken for granted.

To varying degrees across countries, this rise in inflation rates has reflected an unexpectedly strong recovery in demand, particularly in the case of advanced economies that have been able to resort to generous fiscal programs to support households and businesses. This isin a context of restricted access to cheap energy goods and inputs. The inflationary shock coming from higher commodity prices and new restrictions on supply chains as a result of war in Ukraine will accentuate the current dilemma faced by central banks on both sides of the Atlantic. How quickly and intensively to tighten financial conditions in the face of inflation that can no longer be seen as simply temporary and reversible while seeking not to bring down the pace of economic activity or trigger financial shocks (Canuto, 2021a). As we have remarked, the deteriorating macroeconomic outlook has prompted analysts to predict that the Federal Reserve will not decide on a 50-basis point hike at its March meeting, opting instead for 25 basis points.

There is a fear that these economies returned to conditions like those of the early 1980s when the second oil shock occurred while inflation was already high. The bet is that Jerome Powell and his colleagues are not like Paul Volcker, chairman of the Federal Reserve at the time, whose option was to bring down inflation at any cost.

Rising inflation has been broad-based in the U.S. and Germany (Brooks, Fortun & Pingle, 2022). And this was before the war in Ukraine, and the shocks approached heretofore. The rise in U.S. inflation has been broad-based to an extent unprecedented in recent history.. Though this doesn’t address how persistent high inflation would tend to be, it does lean away from its view as reflecting relative price changes in favor of broad, demand-led inflation. Eurozone inflation also looked generalized, though primarily due to Germany.

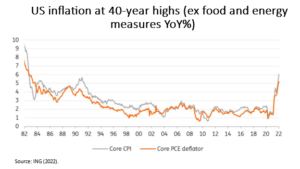

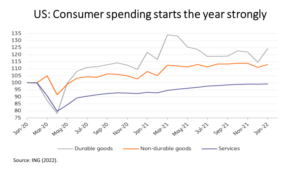

.U.S. inflation has been at 40-year highs, reaching an annual rate of 7.9% in February (Figure 11). The strength of consumer spending at the beginning of the year (Figure 12) favors the perception that inflation reflects a combination of supply shocks and overheating demand, rising above potential GDP growth. It has become hard to argue that inflation is transitory and reversible after the unwinding of supply chain disruptions without necessary tightening of monetary conditions. The point of discussion became the speed and intensity of tightening financial conditions ahead.

Figure 11

Figure 12

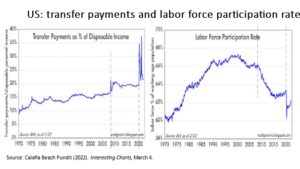

The U.S. February jobs report came strong, also signaling that the “great resignation” has been succeeded by higher labor force participation rates after the decline in transfer payments (see Figure 13).

Figure 13

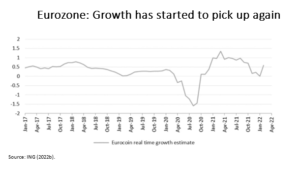

In Europe, an IMF Working Paper released in February estimated that supply shocks accounted for half of the rise in European producer prices in 2021, with the rest linked to sharp increases in demand (Celasun et al., 2022). While growth momentum looked picking up more recently (Figure 14), inflation has been on the rise (Figure 15). Then comes the war in Ukraine and the further round of price and supply chain shocks highlighted.

Figure 14

Figure 15

Although the U.S. job performance and (at least until recently) Europe’s growth prospects looked bright, the International Monetary Fund (IMF, 2022) note to the G20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meetings of February 17–18 highlighted a slowdown in the pace of the global economic recovery. Having revised its forecast for global economic growth this year downwards (4.4%) in January, the IMF cited indicators pointing to the continued weakening of the recovery. Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, not by chance forecasts for the U.S. economic growth this year have been slightly downgraded, as a consequence of worsening financial conditions, higher oil prices, and lower consumer sentiment.

According to the IMF note, the main downside risks suggested earlier have materialized, affecting the recovery prospects. Mismatches between demand and supply availability in multiple sectors, bottlenecks in freight transport, and increases in energy and food prices pushed inflation up.

In several economies, this price increase extended to all categories of consumption. While supply-side shocks could be considered temporary and gradually reversible throughout the year, the perception became that the mismatches between supply and demand would also be reflecting excesses in aggregate demand.

The IMF surveillance note remarked that fiscal support against the pandemic crisis is gradually being withdrawn. It even talked about prospects for a fiscal package in the United States that would be smaller than previously envisioned.

It could not be expected that the unprecedented pace of global growth last year, after the drop in 2020, could be replicated in 2022. However, the note highlights that much of the responsibility for the downward revision of projections in January stemmed from slower growth estimates for the United States and China. In the case of China, they listed the continuity of stress in the real estate market, the low dynamism in private consumption, and the restrictive character of the “COVID-zero” policy.

Well then. How quickly reversible will these shocks be? And what about the level of attribution to give to excess demand regarding the mismatch between demand and supply, even under conditions of normalization of the second? Which variable to look at to see if “temporary” inflation will leave consequences that will require a monetary tightening greater than that then signaled by central banks?

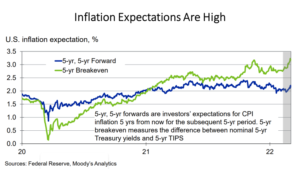

Attention must be paid to two key variables. First, expectations of inflation by private agents. The U.S. inflation forecast for 2022, compiled by Consensus Economics, has shown an increase this year from 2% to 3.7%, slightly above the inflation that serves as an average target for the Federal Reserve. The likely hikes of gasoline and food prices as a result of war in Ukraine will likely lift those inflation expectations – at least according to simulations made by Moody’s (2022). Figure 16 displays U.S. inflation expectations going up.

Figure 16

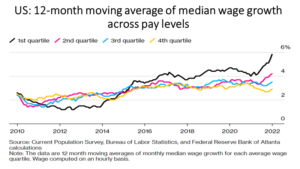

The other variable to watch out for is how prices and wages begin to be readjusted based on previous inflation (Figure 17). The combination of unanchored inflationary expectations and a race between prices and wages would reveal the “transient” as becoming “permanent”. Otherwise, it makes sense for the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank not to accelerate their monetary tightening.

Figure 17

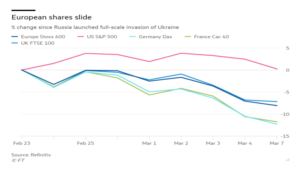

The open question is how over-leveraged financial markets would receive an abrupt or severe change in financial conditions. Central banks will need to balance between curbing inflation and maintaining financial stability. And the war in Ukraine has made such a rope thinner by downgrading economic growth and lifting inflation in Europe and the U.S. Shares on both sides of the Atlantic have shown some sensitivity to such a scenario (Figures 18 and 19).

Figure 18

Figure 19

Emerging market and developing economies (EMDE)

Inflation has also risen in emerging and developing economies, although in most cases not because of excess demand. Its fiscal and monetary stimulus in response to the pandemic did not have the scale achieved in advanced countries, and the recovery of emerging and developing economies in 2021 lagged well behind that of advanced ones. Lower capital inflows and, in some cases, sovereign debt rating downgrades resulted in currency devaluation and domestic import price shocks. On the other hand, they shared with the advanced companies the impacts of supply chain disruptions, and higher prices of energy and food commodities. In large part of the group, the increase in domestic interest rates already started last year, as in Brazil.

It is also worth noting the slower pace of recovery in emerging and developing countries and the increase in the distance between their per capita incomes and those of advanced countries as part of the permanent losses in GDP with the pandemic (Canuto, 2021b). According to the World Bank (2022)’s “Global Economic Outlook” report in January, in 2023 only one of its regions – Europe and Central Asia – is expected to come close to the level of GDP that was projected before the pandemic. Latin America and the Caribbean, the Middle East and North Africa, and Sub-Saharan Africa, will all be at least 4% below what would be the corresponding level. The drama is expected to be even more significant in South Asia, with 8% less.

Both the World Bank and the IMF highlight significant disparities in vaccination rates between countries as a major factor in uneven recoveries. They also highlight the more profound and more extended character of the scars left by the pandemic on the labor markets of non-advanced economies.

The commodity price shocks, and supply chain disruptions brought by the war in Ukraine will bring differentiated impacts on emerging markets and developing economies. Even commodity exporters that might benefit from higher prices will have to pay attention to their impact on poor domestic households and local inflation.

Eastern and Western Europe will be hit via their export exposure to Russia. Rising commodity prices hurt some EMs and benefit others. They may be good news for most of Latin America, because of the corresponding gains of terms of trade of commodity exporters in the region. On the other hand, the already high inflation and the weight of household fuels and food in poor people’s budgets will become a major concern. A major differentiating factor will be whether the EMDE is an energy exporter or importer.

The same applies in the case of African economies (Ali et al, 2022). Food importers in the region will be hit, while exporters of food and vegetable and fish may have an opportunity to increase their share in both Russia and Europe as a result of sanctions and geopolitical dispute. Morocco’s exports of fertilizers may rise, while at the same time the country’s imports of more expensive cereals and oil tend to impact negatively its economy.

How about external finance? Given the small size of Russia’s economy and its efforts to isolate itself from global financial markets, as we approached, a broad contagion to emerging markets is not expected. However, emerging markets that might dream of global relative portfolio reallocation of funds in their favor must recall that overall risk aversion may run against leverage and total volumes of resources. Furthermore, high levels of public and private sector indebtedness increase vulnerabilities and expose them to the risk of some significant tightening of global financial conditions (Canuto, 2022b) – a possible scenario as highlighted above.

Bottom Line

The challenge lies ahead for central banks to find their balanced paths between tightening financial conditions and slowing growth to avoid a subsequent recession. The time lag between monetary policy decisions and their effects is a complicating factor. Central banks will have to cross the river one stone at a time…

Global financial conditions are still relatively accommodative, while vulnerabilities remain high. It is hard to assume that asset prices and the corporate financial situation will emerge unscathed from more drastic adjustments in the face of the reorientation of monetary policies, particularly as the shocks caused by the war in Ukraine will make the policy trade-offs between curbing inflation and avoiding financial instability even more complex. Additional layers of complexity will come in a longer horizon, as geopolitics may become a factor of reshaping international payment systems and supply and demand of commodities.

References

Ali, A.A.; Azaroual, F.; Bourhriba, O.; and Dadush, U. (2022). The Economic Implications of the War in Ukraine for Africa and Morocco, Policy Center for the New South, PB-11/22, February.

Benigno, G.; Giovanni, J.D.; Groen, J.; and Noble, A. (2022). Global Supply Chain Pressure Index: March 2022 Update. Liberty Street Economic, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, March 3.

Brooks, R,; Ribakova, E.; Fortun, J.; and Hilgenstock, B. (2022). Global Macro Views – Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine and EM, Institute of International Finance, March 10.

Brooks, R.; Fortun, J.; and Pingle, J. (2022). Global Macro Views – Where is Rising Inflation Most Broad-Based? Institute of International Finance – IIF, February 17.

Canuto, O. (2021a). Supply Chain Disruptions and Bottlenecks Dampen the Global Economic Recovery, Policy Center for the New South, November 2.

Canuto, O. (2021b). Permanent Output Losses from the Pandemic, Policy Center for the New South, October 21.

Canuto, O. (2022a). Economic Recovery and the Great Reset, In Atlantic Currents: The Wider Atlantic in a Challenging Recovery, Policy Center for the New South, February.

Canuto, O. (2022b). Will emerging economies face a hard landing? Policy Center for the New South, January 26.

Celasun, O.; Hansen, N-J. H.; Mineshima, A.; Spector, M.; Zhou, J. (2022). Supply Bottlenecks: Where, Why, How Much, and What Next? IMF Working Papers W.P./22/31, February 17.

Greene, R. (2022). How Sanctions on Russia Will Alter Global Payments Flows, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 4.

IMF (2022). G-20 Surveillance Note, G‐20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors’ Meetings, February 17-18.

ING (2022a). US Economy Remains Resilient, But There Are Risks Ahead, March 3.

ING (2022b). Stagflation risk increases in the eurozone, March 3.

Moody’s (2022). Geopolitical Risk Rattles Markets, March 4.

World Bank (2022). Global Economic Prospects, January.

Yang, J.; Li, Z.; and Miao, H. (2021). Volatility spillovers in commodity futures markets: A network approach, J Futures Markets, 41:1959–1987.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil.