Policy Center for the New South

Seeking Alpha, and TheStreet.com

In November, U.S. voters will decide who will take control of the White House, the Senate, and the House of Representatives. Kamala Harris, Donald Trump, and their political parties differ significantly on key economic policy proposals that will heavily impact the economy of the country and, therefore, the world. Here, we examine examples in the fields of trade, tax, energy, and immigration.

On trade, although the Democrat administration of President Joe Biden has not been a bastion of free trade—retaining Trump’s tariffs on Chinese imports and recently further selectively increasing tariffs on some Chinese products—a second Trump administration would likely be much more protectionist than a Harris administration.

Among other measures, Trump has already mentioned two possible policies: a 60% tariff on all Chinese imports, and a universal 10% tariff on all imports. While the Biden administration has pursued a ‘derisking’ of exposure to the Chinese economy—alluding to national security reasons—through protectionist policies, blocking access to technology, and subsidizing local production in semiconductors and clean energy, it can be said that Trump’s announcements point towards a complete ‘decoupling’ between the two economies.

As with all mercantilist policies, based on the belief that the adversary loses and local production wins, there is always an underestimation of the negative impacts on all sides, including third countries. Trump’s tariffs on imports from China reduced U.S. manufacturing jobs, as found by Federal Reserve Bank economists in 2019. In addition, U.S. agricultural producers lost share to Brazil on the Chinese market. For those who believe third countries can benefit as ‘connectors’ between the U.S. and China—as Mexico, Vietnam, Malaysia, and others have done since that trade war—it should be noted that a decoupling pursued by the U.S. administration would not leave such connections untouched.

Trump has compared trade wars to boxing matches. An increase in the cost of living for American citizens as a result of tariffs would be part of the impact. Harris has correctly called Trump’s tariff proposal a tax on U.S. consumers, suggesting she is less likely to go further than selective protection.

In the tax field, while the corporate income tax cuts approved by Congress in 2017 were permanent, cuts in individual income and estate taxes expire at the end of 2025. Trump wants to make them permanent for everyone. Harris wants to increase taxes on those earning more than $400,000 a year. Harris’s campaign has endorsed various Biden proposals to tax the wealthy.

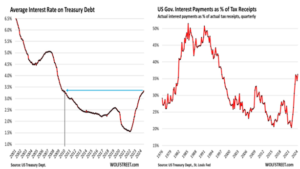

In tax matters, the bipartisan composition of Congress after the elections will be crucial, as ultimately it will determine the success of the tax plans of whoever is president. Both candidates promise to pay for their tax benefit proposals with some form of tax increase: on corporations and the wealthy by Harris, and on imports by Trump. No one believes it will be possible to rebalance lost tax revenue through import tariffs! The taxation issue is becoming more pressing as the fiscal evolution and interest-rate costs are starting to matter more in the U.S. (Figure 1).

Figure 1

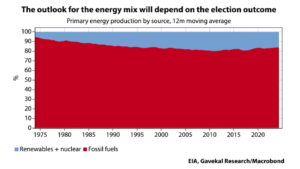

In relation to energy, there are also significant differences between Trump and Harris, with consequences for the battle between fossil fuels and renewables. Regardless of the election outcome, U.S. electricity demand will increase because, among other reasons, of the voracious energy needs of data centers, driven by artificial intelligence.

Republicans, led by Trump, are focused on fossil fuels, promising to ‘drill and drill’. In contrast, Democrats are promising to scale up solar, wind, and geothermal projects. The elections will therefore have implications for the energy transition in the U.S. and thus for the world. Figure 2 shows the recent evolution of the U.S. energy mix and what is at stake.

Figure 2

It’s no surprise that industrial metal prices are shifting depending on electoral probabilities as measured by voter intention polls. Metal prices are sensitive to the election outcome since meeting the growing energy demand with solar and wind energy will put more pressure on the power grid (the response of which will be copper- and aluminum-intensive) than if demand is met with fossil fuels.

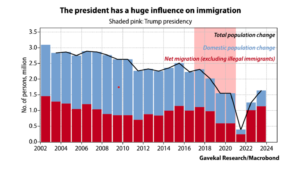

The election outcome is also expected to significantly impact U.S. immigration policy. Harris and Trump 2.0 point to very different immigration policies.

Trump proposes actions such as ending birthright citizenship for people born in the U.S. whose parents are in the country illegally. He has also alluded to the forced deportation of illegal immigrants—something considered difficult to implement according to legal experts. If Trump wins, expect less immigration, as was the case during his first term in 2016-2020 (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Harris, on the other hand, has endorsed policies such as finding pathways to citizenship for immigrants without legal status, especially children. Both Harris and Trump have announced their intention to restrict illegal immigration, but Trump would likely do so more aggressively.

It’s worth noting the role immigration has played in the U.S. labor market. Without the recent return of immigration, the U.S. would not have shown extraordinary performance compared to its advanced peers over the last two years. The increase in labor supply and immigrant demand for goods and services boosted GDP growth, according to a report from the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. Figure 4, taken from this report, shows the recent rise in the U.S. foreign-born population.

Figure 4

For the rest of the world, the differences between Trump’s and Harris’s trade and energy policies also mean significant differences in impact. It is, therefore, no wonder that the rest of the world is closely monitoring the evolution of the U.S. electoral process. If you believe that ongoing global warming is due to carbon emissions and you desire a transition to renewable energy worldwide, and if you believe that trade between countries is not a zero-sum game, you already know who you will be rooting for.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a former vice president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil. Currently, he is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development.