Policy Center for the New South, Seeking Alpha, INTERFIMA, and Roubini EconoMonitor

The Trump government has been imposing restrictions on access to technologies by Chinese telecommunications firms. Why and what are the consequences?

The Federal Communications Commission is about to ban carriers from using government funds to buy equipment from Huawei and ZTE. Other government agencies are expected to take similar measures.

This is just the latest episode of a gradual squeeze that the Trump government has been giving over China’s telecommunications giant Huawei, today the world’s largest telecommunications equipment provider and the second largest phone maker. They only lose to Samsung and even win over Apple.

Over the past four years, parts of the US government, including the executive branch and Congress, have ramped up policy actions against Chinese tech firms on a variety of fronts. These measures have included foreign investment reviews, including Chinese companies on the Commerce Department’s entity list, and more recently, a Congress-led push to examine the role of Chinese tech firms in US financial markets and pension funds.

The concern announced by the US government, shared by other countries, would be the possibility of China’s use of such equipment for espionage, given bed-and-breakfast relations that Huawei has with the Chinese Communist Party. Bed, breakfast and bank account, as the Chinese government has put a few tens of billions of dollars into the company. That attitude has also pleased the “hawks” in the US establishment who dream of a technological containment of rival China.

The tightening includes market access restrictions and technology for all Huawei Group subsidiaries, as well as ZTE. Huawei executives recently admitted that US sanctions are negatively impacting the company as the group has succeeded in replacing US equipment, but not Google’s digital services. The company has been developing its own operating system – “Harmony” – but it is far from getting there.

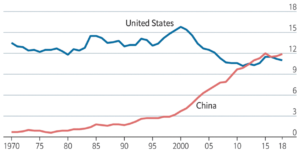

Huawei’s challenges are emblematic of those that China faces at its current stage of development (Canuto, 2019). China’s exuberant history of economic rise in recent decades is that of a climb on the value-added ladder, on the technological scale, in value chains. Access to foreign markets for its products and to available technologies have been key elements of such rise. Chart 1 depicts the evolution of the shares of global merchandise trade by the US and China.

Chart 1 – Global Merchandise Trade (% of total)

Source: UNCTAD

In the beginning, there was the phase of cheap labor-intensive production, employing fully accessible standardized technologies brought by direct investment from outside firms. Investment rates above 50% of GDP were possible due to the absorption of Chinese exports from the rest of the world (Canuto, 2017).

Then came the stage of climbing more technologically sophisticated stairs, for which China resorted to forced transfers by those who wanted to invest there or the use of technologies without recognition of intellectual property. It is important to note that China has also done its homework in terms of investments in education, infrastructure, etc. to creatively absorb this technology (Canuto, 2018).

It has now reached the top of the ladder, where a tacit and idiosyncratic technology content has to be locally developed, as it is not available simply by adapting existing technologies.

This present moment had already been foreseen by the Chinese. In 2011, I was at the Great Hall of People in Beijing when I was one of the World Bank vice presidents and was sent as a representative to celebrate the 10th anniversary of China’s entry into the WTO (Canuto, 2011). I remember then-Chinese President Hu Jintao giving a speech highlighting precisely those challenges for China to reach the top of the ladder. The technological rise would take place as part of a “rebalancing” of the Chinese economy, with domestic consumption and services rising relative to investment and export of manufactures.

The closure of markets and technological access by the US adds to tariffs on purchases of Chinese products, and their combined effect has been the acceleration of the transformation envisaged in President Hu Jintao’s speech. Even before the Trump administration, a trend toward shifting various labor-intensive segments out of China was already in place, toward other countries now with cheaper less-skilled labor, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, Ethiopia, and others.

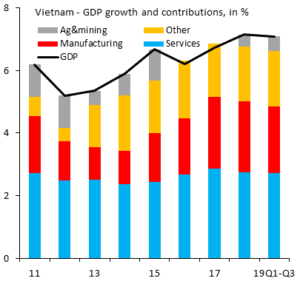

Over the past two years, with the US-initiated war, investors from Taiwan, Japan and the US have already accelerated the transfer of assembly lines and supply contracts in their ITC value chains from China to Vietnam, Thailand, Indonesia and, to a lesser extent, Mexico. Chart 2 illustrates this with Vietnam’s recent high performance in terms of GDP growth led by manufacturing.

Chart 2 – Vietnam: manufacturing-led GDP growth

Source: IIF.

On the other hand, the leap to the top of the technology ladder is what seems to be required long before the expected time…

It is noteworthy that President Hu Jintao, in his 2011 speech, also mentioned the need for a rebalancing between the private sector and the public sector, with the former taking the lead in areas formerly dominated by the latter. Overall, this rebalancing has been set aside by his successor, President Xi Jinping.

This means that the current US government grip on Huawei and others is just a chapter of a soap opera that will take its time to unfold. China’s economic rebalancing, in turn, is speeding up as a result of the trade war.

Otaviano Canuto is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, and principal at the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice president and executive director at the World Bank, executive director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank.