Policy Center for the New South, Seeking Alpha, TheStreet.com

China’s economy grew by 4.7% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2024, after 5.3% in the first quarter of the year (Figure 1). As in 2023, the official target has been set at 5% for 2024 (Figure 2)..

Figure 1

Figure 2

Naturally, great attention has been paid to the decisions of the Third Plenum of the 20th Communist Party of China Party Congress on July 15-18, a four-day meeting in which the country’s leadership sets out the direction of economic policy. The last such event was held in 2018. Do the conclusions of the Third Plenum point out policy actions that will address China’s current economic growth challenges?

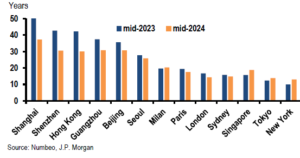

Four major challenges can be identified for Chinese economic growth in the coming years. First is the exhaustion of the real-estate sector as a growth factor, after having reached up to a quarter of the country’s GDP. The restrictions established in 2021 by the Chinese government on access to cheap credit for developers, because of concerns about the size of the real estate bubble—see Figure 3—curtailed the boom but also exposed the fragility of developers’ assets. Since then, there has been a sharp drop in home sales, new construction, and investment in the sector.

Figure 3 – Housing price to income ratio

In this regard, any comprehensive solution to the challenge must include creation of a new source of housing demand. Migrant housing demand may constitute such a source, but that will require a reform of the Hukou system (delinking immigrants and their families from their place of origin and thereby giving them access to public health and education facilities in their place of work). It would also require permitting collectively owned land to be used as collateral for mortgage loans.

The Third Plenum’s decisions refer to such Hukou and rural land reforms. Housing will likely remain a drag on growth in 2024, stabilizing gradually in 2025, but the proposed reforms indicate a political willingness to proceed with a comprehensive new housing strategy.

Local government debt is the second major challenge for the Chinese economy. This debt is linked to shrinking local government revenues from the sale of land to real-estate developers. The degree of exposure of Chinese banks to both, with possible consequences in terms of loan losses, could negatively affect the supply of credit in the economy.

The Third Plenum decisions stressed the need for fiscal policy reform, with the establishment of a fiscal structure under which revenues and expenditures of central and local governments are more precisely defined and better aligned. The decision lacks details on stricter discipline underlying fiscal expenditure, including prevention of new increases in local government hidden debt. In the near term, it will be worth watching whether the government will roll out new measures to mitigate the fiscal difficulties faced by local governments.

The third challenge for growth is a problem with domestic demand by families. Chinese families took on large debts to buy real estate during the boom, and domestic spending cuts have accompanied the housing turbulence. Even though it increased after the end of ‘Covid zero’ last year, consumption remains on a trajectory below that before the pandemic. Measures of consumer confidence point to this. Private investments for the domestic market, as well as hiring, have fallen, accompanying this retraction of domestic consumer demand.

What about the external sector as a form of compensation for the weakness of domestic demand? A fourth challenge to Chinese growth is the external resistance to such an increase in exports as an alternative to domestic demand. This resistance that has followed on from the intensification of geopolitical rivalry abroad, especially between China and the United States and other advanced economies.

The Chinese lead in clean energy technology has, in fact, been accompanied by a strong expansion, for example, in sales of electric vehicles abroad. Chinese passenger car exports have surpassed Japan’s, while Chinese companies are seeking to strengthen their investment positions abroad.

Chinese exports show no sign of slowing, despite new tariffs and extensions to trade restrictions abroad (Figure 4). But the risks that exports will be subject to additional market access restrictions are high..

Figure 4

The Third Plenum showed no change in the Chinese leadership’s approach of stimulating the supply-side of the economy rather than the demand side, and insulating the economy from external threats. Supporting consumption received very little attention. Idle capacity is high in many sectors, reflecting the excess investments relative to levels of demand.

To understand how these four challenges intertwine, it is worth going back to the beginning of the last decade. In December 2011, when I was one of the vice-presidents of the World Bank, I attended a ceremony in Beijing at which then-president Hu Jintao made a major statement about the need for an inevitable “rebalancing” of the Chinese economy. There would have to be a gradual redirection towards a new growth pattern, no longer associated with investment rates of close to 50% of GDP, and in which domestic consumption would increase in relation to investments and exports.

Also, President Hu Jintao said, an effort would be needed to consolidate local insertion in the highest rungs of the added-value ladder in global value chains, something that was effectively sought. Services should also increase their weight in GDP relative to manufacturing. There would no longer be the double-digit GDP growth rates of previous decades, but growth would no longer be, as then-premier Wen Jiabao said in 2007, “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable”.

Given the low level of domestic consumption in GDP (which persists) and, therefore, the dependence on investments and trade balances, the transition would run the risk of experiencing an abrupt drop in the pace of growth. To allay fears of an abrupt slowdown, waves of credit-driven overinvestment in infrastructure and housing followed in later years. A second round was implemented in 2015–2017 in response to a housing slowdown and stock market decline. This was in addition, of course, to the expansion policies adopted during the pandemic crisis in 2020.

In effect, the decline in Chinese GDP growth rates occurred only gradually, to 6% in 2019. Now, however, the lever of overinvestment in real estate and infrastructure has run out. Not only because of the debt levels that accompanied its extensive use, but also because, at the margin, its returns in terms of GDP growth have started to yield a declining contribution.

Two reforms would have a strong effect on growth. First, social protection should be reinforced to convince Chinese people to save less. Furthermore, the proposal made by President Hu Jintao in 2011 to “rebalance” public and private companies should be revived, with a consequent gain in productivity given higher levels of productivity in the case of private companies.

Ahead of the Third Plenum, such reforms did not seem likely to be prioritized, and indeed they did not appear in the conclusions of the Third Plenum. A radical change in the mood of foreign investors since the third quarter of 2023, as well as demographic dynamics in the form of an ageing population, also constitute economic growth challenges for China.

However, even though China’s economic growth path remained steady in the first half of 2024—with exports, manufacturing investment, and travel-related consumer spending compensating for the drag from the property sector—rebalancing demand dependency from abroad to domestic consumers was a glaring absence at the Third Plenum.

Otaviano Canuto is a former vice president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil. Currently, he is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South and a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution.