Policy Center for the New South, Policy Paper PP-24-21

Also at Seeking Alpha, TheStreet.com, and Affluent Society

Abstract

The decade after the Great Financial Crisis of 2007–09 brought significant changes in the volume and composition of capital flows in the global economy. Portfolio investments and other non-bank financial intermediaries are responsible for an increasing share of foreign capital flows, while banking flows have shrunk in relative terms. This paper considers the implications of such a metamorphosis of finance for capital flows to emerging market economies (EMEs). After examining capital flows from the global financial crisis to the 2020-21 pandemic crisis, we analyze the extent to which a normalization of monetary policies in advanced economies may lead to shocks in those flows, as well as why exchange rate fluctuations between the U.S. dollar and other major currencies can affect capital flows to EMEs. Finally, we assess the range of policy instruments that EME policymakers tend to resort to manage risks derived from capital-flow volatility.

The decade after the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007–09 saw significant changes in the volume and composition of capital flows in the global economy. Portfolio investments and other non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs) are behind an increasing share of foreign capital flows, while banking flows have shrunk in relative terms. This policy paper studies the implications of such a metamorphosis of finance for capital flows to emerging market economies (EMEs).

Changes in capital flows accompanied structural shifts in financial intermediation in capital-source countries, with NBFIs increasingly shaping the demand for and supply of liquidity in financial markets. The channels of systemic risk propagation have changed with the higher profile acquired by NBFIs, with leverage fluctuations through changes in margins rising in weight.

Risks associated with capital flows to EMEs have changed accordingly. Foreign capital potentially brings benefits to emerging market economies (EMEs). However, wide swings in capital flows carry high risks to macroeconomic and financial stability, including the adverse effects of sudden stops to capital inflows and challenges faced by economies with weaker institutions and less-developed financial markets.

Capital inflows in emerging market economies are driven by both global and country-specific drivers. The abundance of global liquidity since the GFC has pushed investors to search for yield, with shifts in risk appetite becoming a source of fluctuations. On the other hand, changes in the macroeconomic fundamentals and institutional frameworks of EMEs have made investors more selective.

The weight of global factors came to the fore in the first half of 2020, when the financial shock in advanced economies caused by coronavirus outbreaks led to a substantive wave of capital outflows from emerging markets, with unprecedented speed and magnitude. The shock was mitigated subsequently by central banks’ counter-shock policy moves in source countries, as well as by EME policy tools in managing the risks associated with extreme shifts in capital flows.

This policy paper first examines the metamorphosis of finance and of capital flows after the GFC, up to the shock to capital flows to EMEs during the 2020-21 coronavirus crisis. Then we analyze the extent to which a normalization of monetary policies in advanced economies may lead to shocks in those flows, as well as why exchange rate fluctuations between the U.S. dollar and other major currencies can affect capital flows to EMEs. Finally, we assess the range of policy instruments that EME policymakers tend to resort to when managing risks derived from capital-flow volatility.

- The Metamorphosis of Finance

1.1 Global Capital Flows After the GFC

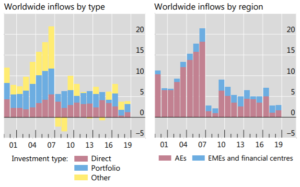

After a strong rising tide starting in the 1990s, gross capital flows reached a peak with the GFC. Figure 1 (left panel) shows how inflows rose rapidly between 2002 and 2007, reaching US$12 trillion (close to 22% of global GDP). After falling steeply during the GFC, flows have trended sideways, never recovering their pre-GFC upward momentum.

Figure 1: Capital Flows by Type and Region (as % of world GDP)

Source: BIS (2021).

As detailed in Canuto (2017) and BIS (2021), the decade after the GFC (2007–09) brought substantial changes both in the volume and composition of global capital flows. When one excludes the significant flows to China, the volume declined globally.

The overall stabilization at lower flow levels has taken place alongside a deep reshaping of cross-border financial flows, featuring de-banking and an increasing weight of non-banking cross-border financial transactions. Sources of potential instability and long-term funding challenges have morphed accordingly.

The post-GFC descent in flows was pronounced for bank loans, which are classified among ‘other’ investment flows in Figure 1 (left panel). Portfolio debt and equity flows were also lower in the post-GFC period, while foreign direct investment (FDI) maintained its strength. Market-based sources of funding replaced banks, while foreign participation in the local markets of EMEs grew. On the borrowers’ side, banks were also substituted by corporates and public-sector entities.

The U.S. dollar has remained the dominant currency for cross-border operations and investments, but the currency composition of flows has become more diversified. As we will discuss later, that has consequences for EMEs.

Another change in composition accompanied the decline in global flows after the GFC, namely, a substantial decline in flows between advanced economies, while EMEs became more prominent as destinations. Financial globalization had mainly happened among advanced economies (AEs). Rising cross-border movements of financial assets from the mid-1990s was remarkable among AEs. Levels of financial openness (the sum of foreign assets and liabilities as a proportion of GDP) relative to trade openness (the sum of exports and imports as a proportion of GDP) were similar for both AEs and EMEs until the mid-1980s, when they shifted upward in the case of AEs, rising rapidly particularly after the mid-1990s (Canuto, 2017). Cross-border financial assets and liabilities went from 135% to above 570% of GDP after mid-1990s for AEs, whereas they moved from approximately 100% to 180% of GDP for EMEs.

The post-GFC global trend mainly reflects changes in flows to AEs, which corresponded to 18% of world GDP in 2007, and then moved down to below 7% after the GFC (Figure 1, right panel). Flows to financial centers comprised part of the trend increase before 2007 but became more volatile between 2009 and 2019. Although the share of world GDP of assets located in financial centers declined, they have remained ascendant over the past decade.

Such flows to financial centers have reflected the financial and tax strategies of multinational enterprises, aimed at minimizing costs and the tax burden. BIS (2021) called it the “financialization of foreign direct investment (FDI).”

Also worthy of mention is the deeper regional integration among EMEs. That is the case particularly of EMEs as FDI and portfolio investors in other EMEs, even though AEs remain the most important funding sources in EMEs across all types of investment.

Some features of “the new dynamics of financial globalization” may bring greater stability (McKinsey, 2017). Higher capital buffers and minimum amounts of liquid assets have reduced the weight of bank lending and the intrinsic features of mismatch and volatility of banks’ balance sheets. The larger share of equity and FDI, in turn, may carry longer-term return horizons and closer alignment of risks between asset purchasers and originators. The unwinding of huge debt-financed current-account imbalances characteristic of the global economy in the run-up to the GFC has also contributed to such a view of global finance entering a more stable phase (Canuto, 2021b, ch.7).

On the other hand, as previously noted, flows of FDI partially correspond to disguised debt flows and/or transfers motivated by tax arbitrage or regulatory evasion. Cross-border debt flows—including securities—in turn, are also sensitive to global factors, besides being highly sensitive and procyclical with respect to monetary-financial conditions in either source and/or destination countries.

There are also ‘blind spots’ left by de-banking, hitherto not preempted by non-banking financial transactions. For instance, cross-border de-risking by global banks has entailed closure of correspondent banking relations in many countries, in which the paucity of alternatives has led to negative consequences for local financial dynamics (Canuto and Ramcharan, 2015). Furthermore, the arms-length distance between asset holders and liability issuers intrinsic to debt securities and portfolio equity, in the absence of the project-finance role played in the past by international investment banks, often constrains the cross-border financing of greenfield investment projects.

Additionally, as we will see below, the rise of NBFIs and market-based intermediation has brought a greater likelihood of, at times of stress, liquidity/maturity transformation and leverage procyclicality, leading NBFIs to a heightened ‘dash for cash’ and sudden increases in demand for liquidity.

1.2. European Banks at the Core of Both Surge and Pause of the Wave of Financial Globalization Since the 1990s

European banks have been at the core of both surge and pause of the wave of financial globalization since the 1990s. The substantial piling up of European banks’ foreign claims in the run up to the GFC was followed by an equally substantial retrenchment (McKinsey, 2017).

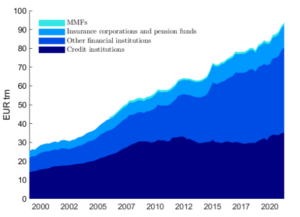

Figure 2 (left panel) shows this. From 2007 to 2016, Eurozone banks reduced their foreign claims by US$7.3 trillion, and other Western European banks reduced their foreign claims by US$2.1 trillion.

Figure 2: Eurozone Banks’ Foreign Claims (2000-2016)

Source: McKinsey (2017).

Lending by European banks was behind two of the major contributing factors to the rising wave of financial globalization. First, the inauguration of the euro, which was followed by markets initially converging their assessments of risk premiums across the zone downward toward German levels, boosted cross-border transactions. According to BIS (2017):

“Between 2001 and 2007, 23 percentage points of the increase of the ratio of advanced economies’ external liabilities to GDP was due to intra-euro area financial transactions and another 14 percentage points to non-euro area countries’ financial claims on the area (p.102).”

European banks also played an active role in the asset bubble-blowing process in the U.S. financial system that preceded the GFC. European banks used U.S. wholesale funding markets to sustain exposures to U.S. borrowers through the shadow banking system. Despite their small presence in the domestic U.S. commercial banking sector, their weight in overall credit conditions was magnified through the shadow banking system in the United States that relies on capital market-based financial intermediaries, which intermediate funds through securitization of claims (Shin, 2012).

From the standpoint of the balance-of-payments between the U.S. and Europe, those transactions netted out. Nonetheless, in an accounting sense they represented short-term borrowing combined with long-term lending by European banks, with a corresponding double counting as cross-border financial transactions.

The retrenchment of European banks’ foreign claims followed both the U.S. asset-bubble burst starting in 2007 and the Eurozone crisis from 2009 onward. Alongside business-driven reasons—losses, decisions to deleverage balance sheets—tighter banking regulation and the orientation toward domestic assets assumed by post-crisis unconventional monetary policies also weighed. These factors have also led to deleveraging, balance-sheet shrinking, and domestic reorientation by banks in the other crisis-affected AEs. Although some banks from outside the latter have expanded their foreign lending, levels of global financial openness have been maintained, thanks to growing flows of non-lending instruments (debt securities, portfolio equity, and FDI).

1.3. Morphing Financial Intermediation in Advanced Economies Behind the Metamorphosis of Capital Flows

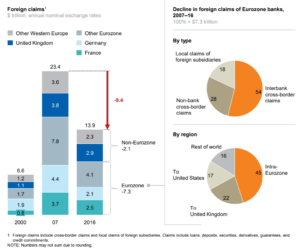

The metamorphosis of global capital flows accompanied the evolution of market-based intermediation in advanced economies, after the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, when the weight of NBFIs in the financial system has risen. Banks—and their affiliated broker-dealers—remain an important component of the mosaic, but they are now part of a broader set of institutions that route the flow of funds and facilitate trading. NBFIs have become more important in debt intermediation, with implications for risk sharing in the financial system.

According to the Financial Stability Board, NBFIs accounted in 2020 for about 50% of global financing activities (FSB, 2020). Figure 3 displays the rise of NBFIs in financing U.S. corporate debt. While, in the 1980s, banks funded about 30% of non-mortgage debt through loans, their share has fallen to 10%; market-based finance (bonds and commercial paper) now comprises 65% of corporate debt. Mutual funds, insurance companies, and pension funds held almost 80% of corporate and foreign bonds as of 2020, with a substantial increase for mutual funds (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Holders of Corporate and Foreign Bonds Among U.S. Financial Institutions

Source: Aramonte et al (2021).

Similar trends have also appeared internationally. Figure 4 shows the rising role played by NBFIs in Europe, particularly by asset managers.

Figure 4: Growth in Bank vs Non-Bank Assets in the Eurozone

Source: Aramonte et al (2021).

The bond holdings of broker-dealers—which are often part of banking groups—diminished after the GFC, even as the overall market expanded (Figure 3). This is quite different from the dynamics pre-GFC, when broker-dealers played a major role in driving the shift from a bank-centric financial system towards a market-based one, and their balance sheets saw a ten-fold expansion between 1990 and 2008, with a corresponding increase in leverage. The role played by European banks that we previously highlighted illustrates that. Since the GFC, regulatory tightening over the activities of banks and their affiliated broker-dealers, demographic changes, and a greater weight of capital markets in providing for retirement, as well as technological change and the pursuit of operational efficiencies, have led to a rising role of market intermediation and NBFIs (Aramonte et al, 2021).

How do stability properties tend to change with such a metamorphosis? NBFIs bring a range of attributes to the financial system and the economy, such as greater diversity in the ecosystem, and the advantage of less-correlated trading motives among intermediaries. NBFIs may fill the gap when banks retreat from certain intermediation activities.

On the other hand, like banks, NBFIs can also feed systemic risk, i.e. disruptions to the activity of a financial intermediary generating substantial costs—particularly as externalities—for other financial institutions or non-financial firms. At times of stress, liquidity/maturity transformation and leverage procyclicality may lead NBFIs to a heightened ‘dash for cash’, suddenly increasing demand for liquidity.

The roles of market prices and of balance sheet management by NBFIs raise new issues. The debt capacity of an investor is increasingly dependent on the debt capacity of other investors in the system, so that leverage enables greater leverage, and spikes in margins can lead to system-wide deleveraging. Deleveraging and ‘dash for cash’ scenarios become two sides of the same coin, rather than being two distinct channels of stress propagation (Aramonte et al, 2021).

The greater weight of NBFIs means that risk exposures are increasingly intermediated and held outside the banking system. Instead of banks warehousing liquidity and credit risks on their balance sheets, such risks are increasingly outsourced to NBFIs. Such structural changes have mitigated counterparty credit risk but have led to a financial system more sensitive to large swings in liquidity imbalances. After all, the business models of NBFIs are typically built around exploiting liquidity mismatches, and tend to, on net terms, provide liquidity in good times. During periods of financial turmoil, however, NBFIs often retrench, and their liquidity supply can suddenly turn into substantial liquidity demand.

We saw such an intense ‘dash for cash’ turmoil in March 2020, at the apex of the pandemic financial shock, when investors shifted away abruptly and massively from risky assets to cash-like assets, thereby making explicit such structural NBFI vulnerabilities with spillovers that impacted other participants in the financial system. Ultimately, it was the central banks’ flexible use of their balance sheets, including the crossing into areas previously considered outside their territory, that stopped the adverse feedback loops and helped to restore market functioning.

Such features of NBFI-based, market-based financial intermediation have been carried over to global capital flows, as the latter have accompanied the former.

- Capital Flows to EMEs

2.1 Capital Flows to EMEs From the GFC to the Pandemic Shock

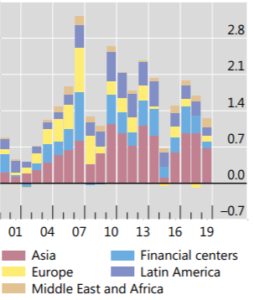

Capital inflows to EMEs held up well after the GFC, even if occasionally passing through high turbulence (Figure 5). They slowed sharply in some years (Canuto, 2013a; 2016; 2018; 2021a):

Figure 5: Capital Inflows to EME regions

Source: BIS (2021).

In June 2013, then-Fed Chair Ben Bernanke suggested that the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) might soon start to slow down its bond purchases. With that one statement, made in passing, Bernanke unwittingly triggered a wave of interest-rate hikes and capital flight from emerging markets.

At the time, the ‘fragile five’—South Africa, Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Turkey—had high current-account deficits and were strongly dependent on inflows of foreign capital. For years, they experienced the spillover effects of ultra-loose U.S. monetary policies, which sent investors seeking higher yields towards emerging markets. When Bernanke raised the possibility of gradual monetary-policy tightening, investors briefly panicked.

Market jitters also happened in 2015 when commodity prices fell and the economic outlook for China deteriorated.

Another bout of capital outflows from emerging markets occurred in May 2018, when the Fed really did start to reduce its asset holdings. But this tapering—followed by a sell-off in U.S. bond markets and dollar appreciation—was halted in 2019. This time, the ‘fragile five’ had been reduced to the fragile two of Turkey and Argentina, both with high current-account deficits and acute vulnerability to exchange-rate fluctuations, owing to their large volumes of foreign-currency debt. Figure 5 shows those years when shocks took place.

Emerging Asia stands out as the one region that saw a sustained increase in capital flows after the GFC. Boosted by China, inflows to emerging Asia doubled between the 2000–07 period and the 2009-19 period, from around 0.4% of global GDP to an average of 0.8%.

2.2. The Pandemic Shock to Capital Flows to EMEs

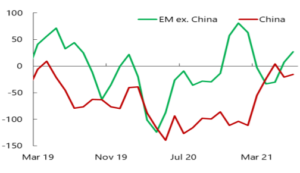

During periods of heightened uncertainty, the typical response of markets is a flight to safety because of risk aversion. Capital flows to EMEs faced such a deep shock at the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis. Although short-lived, capital outflows were larger than at any point during the GFC (Canuto, 2021b, ch.23). While banks’ broker-dealers were in the epicenter of the GFC shock, this time the new features of global capital flows led to a dramatic shock to capital flows to EMEs.

The extraordinary monetary and financial support in major economies stabilized flows to EMEs in the months after May 2021. Overall, the net capital flows have diverged significantly between China and EMEs excluding China (Figure 6). That reflects the simultaneous presence of both common-to-EMEs and country-specific capital-flow drivers, including some substitution effect of capital flows between China and other EMEs.

Figure 6: Net Capital Flows (USD Billions; Monthly)

Source: IMF (2021).

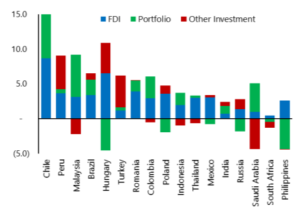

International bond issuance has partially compensated for the outflows from local equities and bonds. In fact, the diversity in the composition of the non-resident flows to EMEs excluding China in 2021 illustrates the diversity of country-specific determinants of capital flows (Figure 7).

Figure 7: EMEs excluding China: Composition of the Non-Resident Flow

(Percent of GDP; 2021 flows)

Source: IMF (2021).

Overall flows to EMEs have performed better than initially expected, particularly considering the severity of the shock, even if the recovery was uneven and incomplete in some market segments. The loss by the governments of several countries of foreign funding in local currency did not reverse. Capital flows to EMEs in 2021 have not maintained the strong pace of the second half of 2020 (IIF, 2021). As attention has shifted to possible implications of reorientation of monetary policies of major AEs to capital flows to EMEs, we consider next what the likelihood is of new capital outflows once it happens.

2.3 Will Another Taper Tantrum Hit Emerging Markets?

Market movements in mid-2021 led to renewed fears that changes in U.S. financial and monetary conditions would trigger a painful wave of capital flight from emerging markets, as happened in 2013. But times have changed, and the greatest risks to emerging markets are now elsewhere (Canuto, 2021a).

In early July 2021, the yield on U.S. ten-year Treasury bonds fell to its lowest level in four months, and stock markets dipped because of fears that the year’s rosy projections for economic growth would not be borne out. Still, as we write, the prevailing view is that the 2021 spike in inflation will be temporary, allowing the U.S. Federal Reserve to pursue a smooth unwinding of its balance sheet at some point in the future.

The July 2021 market episode could be partly traced back to February and March 2021, when U.S. long-term rates rose in anticipation that the Fed might soon start tightening its monetary policy. With U.S. President Joe Biden’s large fiscal packages came new fears about inflation and economic overheating. Ten-year Treasury yields duly increased from below 1.2% to close to 1.8%, before stabilizing and falling back to previous levels. And ten-year Treasury yields started to rise substantially in September and October as it became clear that the U.S. Fed would start tapering its QE before the end of the year and basic interest rate hikes would probably come in 2022.

Though there were some jitters following the June meeting of the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee, when some FOMC members assumed a more hawkish attitude, the Fed nonetheless managed to keep markets cool by promising to give plenty of advance notice before beginning to taper its monthly bond purchases. Since then, interest rates have declined at a notable pace.

But uncertainties remain for emerging markets, most of which suffered capital flight as a result of the February-March tantrum and the attendant hike in U.S. market interest rates. Although these outflows have since reversed, there is always a possibility that the Fed will feel obliged to change tack, leaving open the question of whether we are heading for another ‘taper tantrum’ of the kind that shook global markets in 2013 (see section 2.1).

The February-March market tantrum was enough to generate a significant reduction in non-resident portfolio flows to emerging markets. Although these losses were partly recovered over the following three months, worries of a ‘taper tantrum 2.0’ will remain over the next two years, especially if it starts to look like the Fed will tighten faster than it is currently projecting.

But it is important to remember that we are no longer in 2013. Back then, the fragile five’s (South Africa, Brazil, India, Indonesia, and Turkey; section 2.1) current-account deficits averaged around 4.4% of GDP, compared to just 0.4% in 2021(Canuto, 2021a). Moreover, the flow of external resources into emerging markets in recent years has been nowhere close to as large as in the years before the 2013 tantrum. Nor are real exchange rates as overvalued as they were then. Except for Turkey, the fragile five’s gross external financing needs as a proportion of foreign reserves have fallen substantially.

Two additional mitigating factors are also worth considering. First, if stronger economic growth drives up U.S. interest rates, positive trade linkages for some emerging markets might help to offset any negative financial spillover. Second, it is reasonable to assume that the Fed will offer more appropriate ‘signaling’ this time around, thereby minimizing the risk of another panic episode.

What about the problem of “twin deficits” in many emerging economies? One cannot dismiss the fact that emerging markets suffered large capital outflows last year just as their fiscal deficits were rising in response to the pandemic. But despite the COVID-19 crisis, emerging markets generally have been able to finance their larger fiscal deficits by relying on domestic investors and, in some cases, their central banks (Canuto, 2020). And starting in the second half of 2020, purchases of government securities by non-residents in some emerging markets started to pick up again.

True, because some issuance of foreign-currency-denominated securities may still be necessary, the risks associated with changing foreign-exchange flows have not been eliminated entirely. Countries such as Colombia and Chile still have relatively high levels of dollar-denominated debt, and in some emerging markets, portfolio inflows will remain crucial to financing fiscal deficits.

But, ultimately, the bigger risks facing emerging markets lie elsewhere. Rather than worrying about another taper tantrum, we should be more concerned with the slow pace of COVID-19 immunizations leading to an anemic post-pandemic recovery; commodity price hikes generating inflation; and economic strategies that merely restore the low growth rates of the pre-pandemic era.

2.4. Why a Weakening Dollar Tends to be Good for EMEs

After peaking against other currencies in March 2020, the dollar fell by almost 15% by the end of that year. Asset portfolio managers have been taking ‘short’ positions against the dollar, that is, betting on its future fall. The dollar is expected to end 2021 much more devalued against the euro, the yen, and the Chinese RMB.

The peak during the coronavirus financial shock reflected the search for a safe haven in short-term U.S. bonds or cash that happens in times of heightened global aversion to risk. The dollar rose almost 10% in the first quarter of the year. The mood improvement in the subsequent months reduced the search for safety. There is currently a convergence of views that, gradually or not, U.S. current account deficits and insufficient domestic savings tend to slide down the relative value of the dollar (see, for example, Roach, 2020, and Rogoff, 2020).

This is good news for emerging economies in 2021, judging from an essay by Hofmann and Park (2020), included in the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) Quarterly Report of December 2020. Loose financial conditions and sustained expansion of global credit favor growth on the real side of emerging economies, with the presence of the dollar as an influential factor in this transmission. According to the authors’ estimates, a shock of 1% appreciation of the dollar against a wide basket of other currencies reduces by 0.3 percentage points the economic growth of a group of 21 emerging countries that they consider. One may expect an impact in the opposite direction in the event of a devaluation of the dollar.

The authors highlight four “channels of dollar transmission” to explain the negative correlation between the dollar’s strength and the growth of the global economy. First, the demand for the currency reflects, as a barometer, the global appetite for risk by investors. When the latter collapses, the search for refuge raises the price of the dollar, at the same time as capital outflows and worsening financial conditions at the origins are witnessed, in addition to retraction with respect to higher-risk assets and clients. The dollar rises, while the level of economic activity tends to fall.

Second, there is a mismatch between currencies on the sides of liabilities and assets in global credit in dollars outside the United States, the magnitude of which is considerable. When the dollar falls, balance sheets in which liabilities decline relative to assets in other currencies get stronger. The supply of credit, in turn, increases due to the improvement in risk assessment. This tends to happen even with short-term trade finance.

Third, something in the same direction occurs in the markets for government bonds in local currencies, not least because global investors who carry securities from various countries adjust their portfolios according to the risk conditions of the group as a whole. It is interesting to note that Hofmann and Park (2020) mention a study showing that changes in the dollar against a broad set of currencies weigh more, for securities markets in local currency individually, than changes in the value of the country’s own currency against the dollar.

The fourth channel of dollar transmission is foreign trade. A devaluation of the dollar tends, of course, to negatively affect competitiveness in relation to dollarized economies on the part of those whose currencies appreciate. However, particularly in cases in which invoices are in dollars, there is price rigidity in the short term.

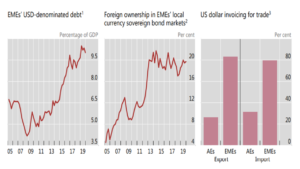

Now, these four channels are particularly relevant in the case of emerging economies. Despite the ‘deepening’ and development of the financial systems of these countries in recent decades, including the expansion of local-currency securities markets, their financial systems still do not have the density of those in advanced economies and are dependent on external financing. It is not by chance that they have relatively high dollar-denominated debt (Figure 8, left panel) and a significant presence of foreign investors as holders of local currency sovereign bonds (Figure 8, center panel). When the availability of sources of foreign exchange hedge is not adequate, local borrowers of dollar funds and external buyers of local currency securities tend to be exposed in relation to exchange rate variations. Finally, dollar trade invoicing is more widespread in emerging market economies than in advanced economies (Figure 8, right panel).

Figure 8: Dollar Debt, Foreign Investors, and Dollar Trade Invoicing in EMEs

(median values)

Notes: 1. Non-banks’ total cross-border USD-denominated liabilities (bank loans and debt securities). 2 Excluding Singapore, Hong Kong and Czech Republic due to lack of data availability. For Korea, data are based on all listed bonds. 3 Latest available data.

Source: Hofmann & Park (2020).

As long as a future downward shift in the dollar is not abrupt, while low interest rates in advanced economies and abundance of global liquidity continue, its transmission via financial channels to emerging economies in general tends to be favorable in the near future.

The weights of the four channels differ by country. For instance, while the trade relationship with the United States and the fourth channel matters a lot to Mexico, the financial transmission channels are more powerful in the case of Brazil. Overall, the estimates of Hofmann and Park (2020) point to a gain.

This is consistent with a previous paper by Samer Shousha, from the Federal Reserve Board, showing that the transmission of dollar movements to emerging economies takes place mainly through financial conditions rather than net exports, and that (Shousha, 2019):

“… the central role of the U.S. dollar in global trade invoicing and financing – the dominant currency paradigm – and the increased integration of EMEs into international supply chains weaken the traditional trade channel. Finally, as expected if financial vulnerabilities are prominent, EMEs with higher exposure to credit denominated in dollars and lower monetary policy credibility experience greater contractions during dollar appreciations.”

It is worth keeping in sight the weight of domestic, country-specific factors. In the experience of the negative financial effect of the appreciation of the dollar in May 2018, it was not by chance that Argentina and Turkey were captured by the storm, because of their particular vulnerability to dollar fluctuations. In Brazil, the possibly favorable tide from abroad will only be taken advantage of if the domestic fiscal mooring is firm. In any case, most EMEs tend to welcome dollar depreciation against a wide basket of currencies.

3. A Policy Toolkit to Deal With Capital Flow Volatility in EMEs

Major risks accompany the benefits of financial development and international financial integration for EMEs (Canuto and Ghosh, 2013). There is the inherent pro-cyclicality of the financial system, amplifying business cycles. Positive shocks tend to lead financial institutions and markets to move in the same direction, feeding asset price and credit booms, and boosting a generalized expansion of economic activity. When the cyclical tide changes, asset prices decline, credit shrinks, and the economic slowdown tends to be deeper because of the enthusiasm during the upside phase. At the extreme, financial crises with major real sector dislocations and large fiscal costs can happen.

Such pro-cyclicality and the accompanying risks of financial crises are also present in international financial integration, and capital flows often have volatile features. But the evolution of financial intermediation in the last few decades, as we have discussed, has accentuated such features as a ‘downside’ accompanying its ‘upside’ consequences.

In AEs, the buildup of banking systems’ vulnerabilities prior to the GFC occurred through complex chains of credit intermediation and related to large gross capital flows, as we have noted. After the GFC, countries undertook measures to strengthen the resilience of their financial systems, including against risks originating abroad. A key component has been to attempt to curb the propensity of financial systems to behave pro-cyclically. Cross-border spillovers have also been tentatively dealt with in the financial architecture.

However, EMEs face greater challenges in dealing with international financial integration and cross-border flows (Claessens and Ghosh, 2013). First, capital flows to EMEs, even in net terms, are often large relative to their domestic economies and overall absorptive capacity—especially relative to the size and depth of their financial systems. Financial flows correspond to much larger shares of the domestic capital markets of EMEs than of AEs.

A second challenge comes from the fact that EMEs are more likely to undergo larger shocks. Their economies are smaller and less diversified, and negative shocks—domestic or from abroad—tend to be exacerbated and propagated more easily in EMEs because of structural and institutional features (such as weaker enforcement of property rights and deficient information infrastructures). Large capital inflows tend to interact with and amplify the domestic financial and real business cycles in EMEs to a greater extent than in AEs.

The challenges to economic and financial sector stability in EMEs brought by international financial integration are significant. Business cycles and financial cycles are more volatile in EMEs than in AEs (Canuto and Ghosh, 2013). Adverse financial cycles combined with recessions, although not necessarily more frequent or longer, tend to lead to worse and deeper losses in EMEs than in AEs. Conversely, recoveries combined with favorable financial cycles tend to be stronger (and faster) in EMEs than in AEs. Capital flow surges and sudden capital outflows are associated with the greatest amplification in business cycles in EMEs.

To manage these risks, as argued by Canuto and Cavallari (2013), EMEs must use a different and broad set of policies, including macroprudential tools, in addition to monetary, fiscal, and micro prudential policies. EMEs are also subject to tighter constraints than AEs on fiscal and monetary policies, and relatedly, more limited headroom. EMEs are likely to have to use a more heterodox mix of policy tools, notably including macroprudential policies, but also capital-flow management (CFM) tools.

Global financial integration has challenged the belief that floating exchange rates would suffice as a response to the ‘Mundell trilemma’, i.e. that free capital mobility, pegged exchange rates, and independent monetary policies are incompatible (Obstfeld and Taylor, 2004). As argued by Rey (2013):

“The most appropriate policies are those aiming directly at the main source of concern (excessive leverage and credit growth). This requires a convex combination of macroprudential policies guided by aggressive stress-testing and tougher leverage ratios. Depending on the source of financial instability and institutional settings, the use of capital controls as a partial substitute for macroprudential measures should not be discarded.”

The IMF’s integrated policy framework designed to help policymakers to face frequent difficult tradeoffs in pursuing domestic and external stabilization objectives, recognizes that, under some circumstances, independent monetary policies are possible if and only if the capital account is managed, directly or indirectly.

A strong macroprudential structure was erected after the GFC but dealing with the pandemic emergency led to the relaxation of regulations in 2020-2021. As discussed by Edwards (2021), in every country regulatory forbearance was given a key role in the response to COVID-19. Rebuilding the macroprudential fabric—including capital-flows management (CFM) controls as macroprudential instruments—will be key to reducing the costs of future systemic shocks.

4. Bottom Line

The transformation of global finance has not suppressed the need for policies to monitor and cope with risks. The greater weight of NBFIs and market-based intermediation has brought changes to the risk landscape.

On the side of recipients of net capital inflows, domestic strategies of institutional strengthening to reinforce alignment of risks between investors and countries, together with regulatory vigilance against excess financial euphoria or depression, remain necessary. The bar in terms of domestic institutional quality—corporate governance standards, business environment—has been raised in the new phase of global finance.

To finalize, it is also worth referring to the potential transformative impact—and corresponding need for regulatory adaptation—of digital technologies on cross-border finance. We may well be on the brink of an additional metamorphosis of global finance, and the instability that could bring.

References

Aramonte, S.; Schrimpf, A.; and Shin, H.Y. (2021). Non-bank financial intermediaries and financial stability, BIS Working Papers No 972, October.

BIS – Bank for International Settlements (2017). Annual report, July.

BIS – Bank for International Settlements (2021). CGFS Papers No 66 – Changing patterns of capital flows.

Canuto, O. (2013a). “QE tapering as a wake-up call for emerging markets”, Capital Finance International, Fall issue.

Canuto, O. (2013b). Currency War and Peace. Project Syndicate, March 12.

Canuto, O. (2016). “China’s spill-overs on Latin America and the Caribbean”, Capital Finance International, Summer issue.

Canuto, O. (2017). The metamorphosis of financial globalization, Policy Center for the New South, September 15.

Canuto, O. (2018). Argentina, Turkey and the May Storm in Emerging Markets, Policy Center for the New South, June 6.

Canuto, O. (2020). Quantitative Easing in Emerging Market Economies, Policy Center for the New South, November 19.

Canuto, O. (2021a). Will another taper tantrum hit emerging markets? Project Syndicate, July 14.

Canuto, O. (2021b). Climbing a high ladder: development in the global economy. Policy Center for the New South, June 6.

Canuto, O. and Ghosh, S.R. (eds.) (2013). Dealing with the Challenges of Macro Financial Linkages in Emerging Markets, World Bank: Washington, DC.

Canuto, O. and Cavallari, M. (2013). “Monetary Policy and Macro Prudential Regulation: Whither Emerging Markets”, In Canuto and Ghosh (2013), p. 119-154.

Canuto, O. and Ramcharan, V. (2015). De-Risking Is De-linking Small States from Global Finance, Nasdaq.com, October 23.

Claessens, S. and Ghosh, S.R. (2013). “Capital flow volatility and systemic risk in emerging markets: the policy toolkit”, In Canuto and Ghosh (2013), p. 91-118.

Edwards, S. (2021). Macroprudential policies and the Covid-19 pandemic: risks and challenges for emerging markets, NBER Working Paper No. 2944, October.

FSB – Financial Stability Board (2020), Global Monitoring Report on Non-Bank Financial Intermediation, Financial Stability Board Report, December 16.

Hofmann, B. and Park, T. (2020). “The broad dollar exchange rate as an EME risk factor”, BIS Quarterly Review, December.

IMF – International Monetary Fund (2020). Toward an Integrated Policy Framework, October 8.

IMF – International Monetary Fund (2021). EM capital flows monitor, September 13.

IIF – Institute of International Finance (2021). Capital Flows Tracker – September 2021 Bond Issuance Saves the Day, October.

McKinsey Global Institute (2017). The new dynamics of financial globalization. August.

Obstfeld, M and Taylor, A.M. (2004). Global capital markets: integration, crisis and growth, Cambridge University Press.

Rey, H. (2013). Dilemma not Trilemma: The global financial cycle and monetary policy independence, VoxEU, August 13.

Roach, S. (2020). “The end of the dollar’s exorbitant privilege”, Financial Times, October 5.

Rogoff, K. (2020). The calm before the exchange-rate storm? Project Syndicate, November 10.

Shin, H. S. (2012). “Global Banking Glut and Loan Risk Premium. 2011 Mundell-Fleming Lecture”, IMF Economic Review, 60 (July), p. 155–92.

Shousha, S. (2019). The dollar and emerging market economies: financial vulnerabilities meet the international trade system. Federal reserve System, October.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil.