T20

TF7: Infrastructure Investment and Financing

Risk mitigation tools to crowd in private investment in green technologies

Mahmoud Arbouch, Policy Center for the New South

Otaviano Canuto, Policy Center for the New South

Raffaele Della Croce, Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

Karim El Aynaoui, Policy Center for the New South

Youssef El Jai, Policy Center for the New South

Miguel Vazquez, SDA School of Management, Bocconi University

Abstract:

In order to close the financing gap in green technologies, finding new mechanisms to enhance the participation of the private sector, combined with that of the public sector, in financing sustainable and climate-resilient infrastructure is a must. In this context, some unlisted instruments are going to be needed to enhance financing of green infrastructures. Besides, the development of properly structured projects, with risks and returns in line with the preferences of the different types of investors and financial agents that make up the ecosystem of financing sources, would also help to close the private financing gap in infrastructure.

Challenge:

The Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) report (2012) highlighted the pressing infrastructure needs of African countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Sustainable infrastructure in Africa are still today the missing link towards deeper integration of the African continent. The lack of physical and social integration costs the continent 2% in annual growth. For example, back then, the energy sector needed around $30 billion in investments per year, in order to match by 2040 a projected six folds increases in energy demand. As things stand today, the first step of the PIDA program failed to achieve the needed interim objectives. The selection process faced many hurdles but the most important aspect is that the quantity of projects considered under the first phase came at the expense of quality (African Union, 2020). In particular, some projects failed to align with the goals set by the 2063 Agenda of the African Union and this lack of efficiency in the selection process hindered the full participation of the private sector.

Consequently, there is an urgent need to find new mechanisms to enhance the participation of the private sector in financing sustainable, climate-resilient infrastructure in the African continent, combined with the participation of the public sector. Indeed, according to the latest Global Infrastructure Hub (GI Hub) outlook, risks that are contingent to infrastructure projects peak during the construction phase. During that phase, the private sector is very reluctant to engage in a project without the appropriate guarantees. Furthermore, climate risks associated with climate change have both a direct and an indirect impact on the sustainability of existing infrastructure. On the one hand, the probability of fat-tail events (e.g. natural disasters) increases. On the other hand, climate risks can lead to an increase in the total cost of projects including an increase in the share of the capex that accrue to the private sector.

Developing countries’ rising demand for energy has mostly been met with fossil fuels. Today, in order to move forward in their decarbonization plans and meet the climate agendas, these countries most work on shifting their infrastructure investments to green infrastructure, by developing more low-carbon, and climate-resilient infrastructure, especially in the energy field. Such a shift, can strongly enhance a structural change in infrastructure investment, and be a trigger for a sound economic development, spurred by a green growth. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), every additional dollar invested today in clean energy can generate three dollars in future fuel savings by 2050[1].

In this context, governments have a key role to play in strengthening the enabling environment for green infrastructure investment. By doing so, the public sector will mitigate the inherent risks to the investment in infrastructure projects in general – and to green ones in particular – and allow the private sector to invest in green infrastructure projects. In particular, what can the private sector exactly bring in green infrastructure investment?

- Avoiding the lock-in to carbon-intensive development pathways.

- Reducing fossil-fuel reliance for energy importing countries.

- Creating domestic jobs by including national SMEs in the investment process.

- For green energy infrastructure, the private sector expertise can facilitate cost-effective access to energy in rural and remote areas.

- The private sector know-how may foster innovation.

Given the current strains on public finances, because of the huge spending to face the Covid-19 crisis, and the considerable infrastructure (and particularly green infrastructure) gaps, achieving this green transition will entail leveraging both international and domestic private financing. Private investment in green infrastructure however remains seriously constrained by some investment barriers, such as high upfront costs, high perceived risks, and long investment timelines compared to fossil-fuel based alternatives.

Our analysis builds on the idea that unlisted instruments are going to be needed to enhance financing of climate-resilient projects. We analyze the role of the public sector in mobilizing finance (public and/or private) to facilitate investment in green infrastructure. We organize the analysis around two broad dimensions: i) measures to facilitate financial challenges, and ii) measures to facilitate market regulation/contract design.

Proposal:

Dimension #1: Financial measures to facilitate investment

There is a big gap between the needs for investment in infrastructure in a substantial part of the world economy and the abundance of financial resources in search of investment opportunities with returns greater than those of low-risk assets. With rare exceptions, such as China, investment in infrastructure has remained below what is necessary to expand the countries’ potential growth[2].

While financial resources in world markets are facing low long-term rates of return, opportunities for greater potential returns with infrastructure assets are being lost. The development of properly structured projects, with risks and returns in line with the preferences of the different types of investors and financial agents that make up the ecosystem of financing sources, would help to close the private financing gap in infrastructure.

Investors and financial agents have different mandates and their own competences regarding the management of risks associated with types of projects and phases of investment project cycles. They demand coverage of risks whose exposure is not adequate or permitted by regulation. The absence of complementary instruments or investors is one of the causes most often pointed to failure in the financial completion of projects.

Defining attractive investment opportunities for different types of investors and combining these perspectives more systematically around specific projects or sets of assets is a promising way to bridge the infrastructure financing gap. The planning and integrated issuance – with different time profiles – of fixed income securities, bank loans, credit insurance and others for the different moments from the preparation to the operation of projects make that combination possible.

Additionally, as observed in multiple consultations with stakeholders, they highlight the relevance of having financeable project pipelines with homogeneity, quantity and comparability that stimulates them to create technical analysis capacity and to invest in financial intermediation.

Lately, the interest with respect to infrastructure finance has turned to climate-resilient projects (which we will call generically “green”). They represent a particularly important subset of infrastructure projects, because green projects are unlisted investments makes data gathering very difficult. In that sense, improving project data disclosure would be helpful for financial institutions. Moreover, regulated requirements on disclosure (transparency) may accelerate the creation of international benchmarks.

Moreover, with the aim of facilitating the creation of a pipeline of projects, clarifying the meaning of “green infrastructure” seems necessary. To that end, a standard taxonomy of green investment needs to be created (as globally as possible). Correspondingly, this taxonomy requires the institutional architecture to define it. When considering Africa’ infrastructure projects, the definition of the above taxonomy requires to strike a balance between climate resiliency and social relevance.

On the other hand, all of the above measure are oriented fundamentally to facilitate financing of long-term contracts. However, market environments that impose the development of infrastructure under the same framework of traditional projects may create undesired constraints. This challenges the adequacy of a convergence to a pure infrastructure-like market design. In particular, mitigating risk implies that investors are not facing the risk that technology may be substituted (or become obsolete), even if it exists. The counterpart of the long-term contract, who is typically a regulated consumer, absorbs this risk. Furthermore, if the riskier contracts are discouraged, technological flows channeled through utilities will face barriers to be developed[3].

In summary, interesting lines of action are:

- Risk mitigation instruments must adapt to the financial ecosystem – Financial instruments offered to the private sector may not be adapted to potential consumers (those who aim to lend). For example, offering relatively short-term debentures has, in theory, the logic of structuring investments that enhance the main loan (“base facility”). However, due to the short-term characteristics of the product, the buyer will not (normally) be an institutional investor. Potential buyers, typically banks, would normally prefer a loan, as it is a more liquid instrument.

- Avoid “crowding out” – Any long-term loans from the private sector must compete with public loans. In this sense, there is a risk of creating barriers to entry into the private sector. Note that it is not enough to just reduce the volume of public sector loans (ie when the public sector loan runs out, SPEs would use the most expensive instrument), as the profitability of projects when they enter into concessions is often calculated in relation to this loan. More expensive loans make projects unfeasible

- Changing the role of public financing – Optimizing the role of public financing implies acting on the risks in which the private sector perceives more difficulties. One of the potential objectives would be subordinated debt (in general, “mezzanine” financing): an instrument that absorbs credit loss before senior debt, which increases the quality of that senior debt. In this sense, subordinated debt can be designed with different risk / return rates, constituting a bridge between traditional debt and equity[4].

- In relation to “green investment”, relevant measures would be: i) disclosure of climate change risks for infrastructure assets, and ii) standardization, taxonomy and green definitions.

Dimension #2: Market design measures

As noted by Arbouch & Bourhriba (2020) and Hausmann (2018), long-term contracting has been systematically used as a tool to coordinate public and private forces to deliver crucial infrastructure. Traditionally, governments often choose to bare the risks related to the construction phase and some risks related to the operation in order to ensure the full compliance of the private operators. This allows countries with limited fiscal space to build green infrastructure and reduce their funding gap. Moreover, new investments in crucial infrastructure can have strong spillover effects on job creation and the creation of peripheral activities. However, while these mechanisms are particularly useful, they do not come without drawbacks. Perhaps, the most important one is the challenge of moral hazard that comes with risk mitigation by the public sector (Mann, 2018). Excessive risk-taking by the private operator sometimes leads to the accumulation of liabilities on the governments’ balance sheet. Another important aspect relates to the contracts per se, which are systematically renegotiated, often to the benefit of the private contractor.

A well-designed contract to finance green infrastructure starting point should be the fact that, green infrastructure projects are sufficiently similar to other infrastructure projects and should rely on proven project financing approaches. The key difference is that many green infrastructure investments require financial support to mitigate externalities, which private sector stakeholders alone have no ability to afford.

Second, many green infrastructure investments require subsidy support, but this is not different from any other infrastructure projects. In many green infrastructure projects, blended finance is used, and this schemes are more common as projects become more complex and not viable by relying only on a private sector financing.

Finally, a well-designed contract to finance green infrastructure will accelerate investment in green technologies by resolving their financing challenges. As such, the focus should be on obstacles that have impeded the financial closure of green infrastructure investments. Moreover, the successful financial closure of low-emission projects will improve their contribution to the climate change mitigation by locking new investments into clean technology over their lifetime, while displacing low-cost polluting alternatives. This is significant as carbon mitigation initiatives often deal with emissions of pre-existing assets rather than introducing new clean investments.

African case studies

As stressed in the challenges, Africa is today the continent where the investment needs in infrastructure are more pressing. Also, according to the latest projections by the IPCC, it is more exposed to global warming. This calls a novel approach to finance resilient and sustainable green infrastructure. Previous studies have shown the importance of sound infrastructure in enhancing growth. For example, Agénor et al. (2008) study the link between foreign aid, public investment in infrastructure, growth and poverty. They find that aid, coupled with reforms, has a positive impact on growth and poverty.

- Morocco:

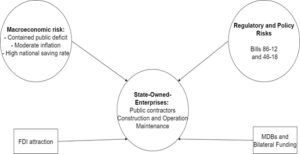

In light of the recent advances made by Morocco in modernizing its infrastructure, this country offers an interesting perspective on how other African countries can rely on the public sector with the participation of the private sector in building sustainable green infrastructure, capitalizing on a strong involvement of the government and state-owned enterprises, in special Public Private Partnerships (PPP) schemes.

First, to ensure the consistency of the decisions with the legislative cycles and avoid discretionary changes, the parliament has adopted a framework for PPP implementation through the bill n°86-12 that was voted in 2014 and amended in 2020, through the bill n°46-18. Both bills insisted on the importance of PPPs as mechanisms that would help the country achieve long term goals of sound and sustainable infrastructure that can help achieve social inclusion and improve the quality of the offer of public services. Also, the initial bill came with a standardized definition of a PPP contract with its different clauses, while the amendment bill cleared the way for private sector participation in structural projects, with significant social returns. Both emphasized the importance of transparency in the process of procurement and the importance of information disclosure.

Second, throughout the last two decades, and with the exception of cyclical events, Morocco has kept a sound macroeconomic framework, based on strong fundamentals and a moderate but sustained growth rate. This helped the country improve its overall business climate and its attraction of foreign direct investment in crucial areas like renewable energy, port infrastructure, or the new industrial zones, giving the much needed visibility to the private investors to correctly assess the returns of infrastructure projects. For example, between 2014 and 2018, the statistics of the foreign exchange office of Morocco show an increase of two folds of the total stock of investment in the Energy and Extraction sector.

The last ingredient of the Moroccan model, and perhaps the most fundamental, is its reliance on state-owned enterprises who are the main operators of infrastructure in the country (e.g. Autoroutes du Maroc, Tanger Med etc.). State-Owned enterprises sign the contracts on behalf of the government which, in theory, should ensure the sustainability of the long term relationship between the private and the public contractors and prevent political and bureaucratic interference in the operational decisions. State as the main (only) shareholder, acts as an underwriter for its enterprises, providing guarantees to the private partners. In practice, problems of coordination and suboptimal governance of some of these SOEs prevail. This has led the country to reform the governance of the public enterprises through the creation of the Mohammed VI fund and the new agency of state’s participation, that will be in charge of transforming the public enterprises. One particular expected advance is the integration of the infrastructure operated by these entities in their balance sheet as a proper asset.

Figure 1 The Moroccan Model of Infrastructure Development, authors.

Thanks to this model, Morocco has been able throughout the last two decades to strengthen its infrastructure assets and enlarge the coverage in basic infrastructure such as roads, water and electricity to a large share of the population. Three specific programs have been fundamental in that course.

First, Le Programme d’Electrification Rurale Globale (PERG) which has enabled the country to enlarge its coverage of electricity in the rural areas. The program was run and partly financed by the National Office for Electricity, with Multilateral as well as private funding, based on a collaborative approach with the rural households. A major component of that program was its reliance on renewable energy technologies, through a pilot phase then a generalization through a fee-for-service scheme that opened the way to private provision.

Second, Programme d’Approvisionnement Groupé en Eau potable des populations Rurales (PAGER) for access to drinking water run and financed by the National Office for Drinking Water (ONEP), another public entity, in partnerships with the local communities, the beneficiaries as well as concessional loans from MDBs. This program has helped more than double access drinking water in rural areas throughout the last two decades. It also had indirect effects on the overall enrollment in basic educations as rural children.

Finally, the Programme Nationale des Routes Rurales (PNRR), launched in 1995 has helped expand the network of rural roads. The coverage in rural roads went from 54% in 2005 to 80 in 2017. This project was piloted by the Moroccan Ministry for Equipment and Transportation, and financed by MDBs, especially the World Bank. A survey held by the latter institution showed that the project helped increase the girls’ access to basic education by 7,4%.

2. Sub-Saharan Africa:

Private participation to infrastructure investment is hampered by the poor quality of local legal and regulatory environments, weak project preparation capacity, and underdeveloped or untested public/private partnership arrangements. These challenges are compounded by weaknesses in institutional and funding arrangements, including for the setting up of special purpose vehicles, the process of issuance of project bonds and as regards arranging private placements and syndications, all of which would normally be precursors to or accompany the process of issuing listed securities.

As we observe in many jurisdictions over the world, long-term finance for infrastructure is largely dependent on unlisted products. As we pointed out in the general analysis, one of the main challenges for the creation of more organized markets providing long-term funding is the lack of more standardized projects. This likely limits the development of deeper markets for corporate finance, thus making larger developers to face the need of relying on the banking system, which normally has a strong preference for short-term contra challenging for infrastructure investment.

Several reforms in SSA countries have created growing private pension systems[5]:

“The Nigerian pension industry grew from USD 7 billion in 2008 to USD 25 billion in 2013; total assets under management in 10 African countries in 2015 reached close to USD 380 billion, with South African pension funds managing a commanding share of 85% of these assets (USD 322 billion).”

These institutional investors, on the other hand, represent a small fraction of project funding. An alternative could be to consider domestic capital markets in SSA There are some emerging hubs, such as Nairobi and Lagos[6], but short-term liquidity is still limited. In that view, except South Africa, the depth of equity markets in SSA relatively low in terms of capitalization and liquidity of equity markets. In that context, we observe that funding of infrastructure projects largely relies on government funding, donors and foreign direct investment.

Concluding remarks:

We may identify two elementary business models associated with green investment: i) The “utility business model” is based on a firm that undertakes long-term investments and recover them by selling the output through 1-2 year contracts; ii) The “infrastructure business model” is based on selling the output of an infrastructure through long-term contracts.

Financial structures in both types of business models are considerably different.

We may summarize the requirements of each model as: short-term contracting requires liquid capital markets; long-term contracting requires planning. Although there are no silver bullets, the market design needs to be coherent in order to attract private investment for green infrastructure projects. Hence, measures to facilitate them will differ depending on the requirements of the green infrastructure considered.

The challenge today is how to get to take the collaboration of the private and the public sectors to the next step. In other words, how can we assess and mitigate the risks that are inherent to green infrastructure projects? The momentum given by the on-going ecological transition and the risks stemming from climate change call for a comprehensive and global approach to infrastructure and for an extended reliance on digital infrastructure as well, fully embracing green technologies, in all phases of the projects. It also calls for the production of a proper taxonomy of green infrastructure in Africa and in producing standardized tools and time-consistent contracts, in order to align public and private incentives.

References:

African Union –NEPAD. 2012. Study on Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA).

African Union. 2020. L’Approche du Corridor Intégré – « Un cadre holistique de planification de l’infrastructure pour établir le PIDA-PAP 2 ».

Agénor, Pierre-Richard & Bayraktar, Nihal & El Aynaoui, Karim, 2008. “Roads out of poverty? Assessing the links between aid, public investment, growth, and poverty reduction,” Journal of Development Economics, Elsevier, vol. 86(2), pages 277-295, June.

Arbouch. M, Bourhriba. O, 2020. “African Infrastructure Development: What should be done to win the next decade?” Globsec Policy Institute

Arbouch. M, Canuto. O, Vazquez. M, 2020. “Africa’s infrastructure finance”, Policy Brief for the T20’s TF3: Infrastructure Investment and Financing.

Canuto. O, Liaplina. A, 2017. “Matchmaking Finance and Infrastructure.” Policy Brief PB 17/23. Rabat: Policy Center for the New South.

Della Croce. R, Fuchs. M, Witte. M, 2016. “Long-Term Financing in sub-Saharan Africa.” Banking in sub-Saharan Africa Recent Trends and Digital Financial Inclusion (2016): 143.

Hausmann, R. “The PPP Concerto”, appeared on Project Syndicate on April 30th 2018.

Mann, H. “The High Cost of “De-Risking” Infrastructure Finance”, appeared on Project Syndicate on December 26th, 2018.

OECD/IEA. 2012. “Energy Technology Perspectives : Pathways to a Clean Energy System. ”

Vazquez, M., 2018. “Financing the transition to renewable energy in the European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean”, Policy Brief, 2018/12, Florence School of Regulation.

[1] Energy Technology Perspectives 2012: Pathways to a Clean Energy System, OECD/IEA

[2] Canuto, Otaviano, and Aleksandra Liaplina. “Matchmaking Finance and Infrastructure.” (2017).

[3] Arbouch, Canuto, Vazquez, “Africa’s infrastructure finance”, Policy Brief for the T20’s TF3: Infrastructure Investment and Financing, 2020.

[4] Vazquez, M., “Financing the transition to renewable energy in the European Union, Latin America and the Caribbean”, Policy Brief, 2018/12, Florence School of Regulation.

[5] See Della Croce, Raffaele, Michael Fuchs, and Makaio Witte. “6. Long-Term Financing in sub-Saharan Africa.” Banking in sub-Saharan Africa Recent Trends and Digital Financial Inclusion (2016): 143.

[6] Ibid.