Policy Center for the New South

TheStreet.com, Seeking Alpha

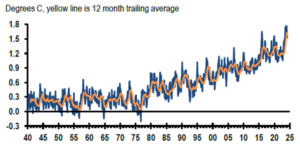

The earth’s average surface temperature in May 2024 was higher than any other May on record, marking the twelfth consecutive such record-breaking month. According to the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, May’s temperature was 1.52 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial average, while temperatures over the past twelve months have averaged 1.63°C above (Figure 1). Global sea surface temperatures have also set records over the past fourteen months.

Figure 1: Global Surface Temperature Increase Over Pre-industrial Temperatures

Source: Malcolm Barr (2024), The pushback on policy to limit climate change, in JPMorgan, Global Data Watch, June 21 (with data from Copernicus Climate Change Service).

Consider the extreme weather event of the floods in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, in April and May 2024. A World Weather Attribution study has already estimated that the likelihood of this phenomenon happening has been more than doubled by climate change, in combination with El Niño, the intensity of which has increased by 6% to 9%.

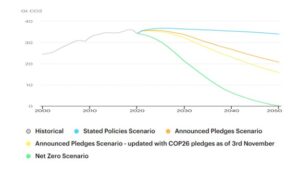

Not surprisingly, scientists point out that actions taken in the remainder this decade will be critical if the world is to to achieve the goal of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which is to limit human-caused climate change to below 2°C, with the hope of not exceeding 1.5°C. In the wake of the COP26 Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in 2021, the International Energy Agency updated its CO2 emissions scenarios in its World Energy Outlook (IEA, 2021), taking into account the country pledges then made. Despite a steeper decline in emissions, the world still remains far from reaching the dreamed-of net-zero emissions scenario by 2050 (Figure 2). Whatever happens in the current decade in terms of emissions will have consequences in terms of climate change in the future (Canuto, 2021).

Figure 2: CO2 Emissions Scenarios Over Time, 2000-2050

Source: IEA (2021).

As well reported by Malcolm Barr in a JP Morgan Global Data Watch report issued on June 21, 2024, the assessment discussed at COP28 in Dubai last year concluded that the world is not on track to meet these goals. There are doubts about whether countries’ nationally determined contributions (NDCs) will add up to deliver sufficient reductions in greenhouse gas emissions globally to limit global warming, or whether countries will individually take the necessary actions to implement their individual plans.

There are also doubts about whether financial flows from developed countries to developing economies, promised to help the latter transition to green energy and production, and to mitigate the ongoing climate effects, will be large enough.

COP30, in 2025 in Belém, Brazil, is expected to bring a new complete set of NDCs, covering at least the period up to 2035. Nothing similar is scheduled for COP29 in November this year, in Baku, Azerbaijan. The proof that COPs are helping deliver more effective commitments by countries to limiting climate change will be seen if countries cut their emissions much faster, and if more resources for developing countries are secured.

Unfortunately, recent political developments have signaled that efforts to limit climate change face risks and delay.

For example, popular support is rising for right-wing politicians in Europe. Although the European Union (EU) has long positioned itself as a leader in efforts to tackle climate change, it has become increasingly common for its right-wing parties to question the speed and necessity of its environmental policy. This has already led to the dilution of parts of the EU’s European Green Deal package.

This is not uniform across the region, considering, for example, that in the United Kingdom, polls suggest that the Conservative Party, which has diluted climate commitments, is expected to lose elections to the more carbon-neutrality-committed Labour Party. On the other hand, the gains for the political right in recent European parliamentary elections, as well as—based on current polls—its likely ascent in French parliamentary elections in July, are challenging the previous consensus around environmental policy.

In the United States, the possibility of a Trump return to the presidency does not bode well for the carbon-emissions reduction agenda. During his previous term, Trump withdrew from the Paris Agreement, a move reversed by his successor Biden. Trump’s climate change skepticism was evident during his first term, but the candidate has nonetheless referenced his disagreement with Democrats’ commitment to US climate policy.

Trade tensions over electric vehicles (EVs) also do not help. China has prioritized industries associated with the green transition as part of its multi-year strategic policy, as a means of addressing its structural growth challenges. It has taken market leadership positions in various related sectors, including batteries and EVs.

The EU recently announced tariffs on EV imports from Chinese manufacturers, arguing that they have benefited from unfair state support compared to EU producers. In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act has subsidies and incentives for the green transition primarily tied to value added within the U.S. Objectives of ensuring that jobs and activities within their own borders are prioritized as the green transition occurs, make this transition more costly and likely less effective.

In summary: the evidence that the damage from climate change has already arrived and will increase is irrefutable. The situation will only get worse if the world fails to reduce carbon emissions—which will depend on countries establishing and fulfilling appropriate NDCs. Recent political developments in countries with significant influence on this trajectory do not seem promising. We can only hope that this evolution does not bring greater consequences for the ‘road to decarbonization’.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a former vice president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil. Currently, he is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development