Pathways for Reconciling New Industrial Policy and International Cooperation for Global Goods

T20 Policy Brief (2024 Brazil) – Trade and investment for sustainable and inclusive growth

Otaviano Canuto, PCNS, Morocco

Sandra Rios, Cindes, Brazil

Renato Baumann, IPEA, Brazil

Abdelaaziz Ait Ali, PCNS, Morocco

Mahmoud Arbouch, PCNS, Morocco

(download PDF)

Abstract:

The resurgence of Neo protectionism as a reality is creating a pressing need to establish New Industrial Policies (NIPs) capable of striking a balance between Global Value Chains (GVC) managers’ quest for efficiency and policy makers’ need for more increasing resilience or national security in a turmoiled geopolitical landscape. Furthermore, although NIPs might pursue legitimate non-economic objectives, they are often captured by vested interests, resulting in protectionist measures. These policies produce negative spillovers, jeopardizing other countries’ development perspectives. This policy brief posits that countries embracing industrial policies with trade diversion components must allocate efforts to implement additional trade liberalization in sectors where the affected exporting countries have comparative advantages as compensation for the negative spillovers their unilateral domestic policies impose on third countries. This highlights the need to establish a structured system that penalizes protectionist countries for exceeding predetermined limits on subsidies and distortive measures. This policy brief also recommends that advanced economies implementing industrial policies with high amounts of embodied subsidies contribute to an international fund dedicated to financing developing economies’ access to new green technologies. This approach acknowledges the undeniable push towards aggressive industrial policies, yet simultaneously strives to establish a framework to temper this emerging trend. This mechanism aligns with the principles of economic fairness and encourages nations to adopt less distortive behaviors in their pursuit of economic security or resilience to shocks.

Keywords: Neo protectionism, NIPs, GVC, Trade liberalization

Diagnosis of the issue:

The foundational questions surrounding the efficacy of our current economic system have taken on a renewed urgency, revealing some flaws -though exaggerated- in its ability to drive broad-based growth and share its dividends across the population. These concerns have gained momentum at least in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and have been further exacerbated by successive challenges—from the COVID-19 pandemic to the war in Ukraine and the looming climate crisis. The rise of China has also “disrupted” the current equilibrium and ushered likely a new era. As a result, we find ourselves at the precipice of a paradigm shift in the global economic landscape. This transformative context has paved the way for populist and nationalist ideology to climb the ladder of power and deploy its classic strategy. Policymakers were tempted to rethink traditional approaches and take shortcuts to fix the system by pivoting from market-centric resource allocation instruments or at least soft-instruments to more proactive, aggressive, and, most notably, self-assured industrial policies.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the global economy was already experiencing stagnation due to the enduring impact of the GFC. This crisis not only slowed economic activity but also fundamentally altered the economy’s trajectory, severely affecting long-term growth. The underlying causes of this trend are well documented, highlighting the GFC’s long-term effects on the global economy’s supply capacity. A significant factor in this downturn is the deceleration in labor productivity (Graeme B. Littler, 2020). Additionally, the lack of investment following the GFC further compromised the recovery, leading to weakened economic prospects and maintaining the global economy at a diminished equilibrium. Despite originating in the USA and predominantly affecting developed economies, emerging and low-income countries also suffered post-GFC losses. A decade after the crisis, the output in over 60% of global economies remained below their pre-crisis trends, indicating that for many, the GFC marked the end of a period of rising productivity growth and ushered in a prolonged period of stagnation.

Additionally, the GFC has exacerbated economic inequalities, posing a significant hurdle to achieving a more inclusive economy. While opinions vary on the extent of the crisis’s impact on inequality, evidence suggests that the most vulnerable segments of the population, particularly in developed countries like the United States, bore the brunt of its adverse effects. Nations experiencing the most substantial reductions in output relative to their pre-GFC levels also saw the most severe deterioration in income equality (IMF, 2018). The economic recovery that followed favored the wealthiest, further exacerbating hardships for the poorest groups. This disparity is particularly pronounced in the USA, where, ten years post-crisis, the bottom 50% of the population continues to face significant challenges in regaining lost ground (Blanchet et al., 2019).

In the meantime, emerging economies, with China at the forefront, have begun to solidify their role as the main drivers of economic growth. The global financial crisis primarily impacted developed economies, allowing emerging Asian economies to demonstrate resilience and perform relatively well during this period (Park et al., 2018). Consequently, economic activity in Asian markets has become a primary contributor to global economic growth. This shift represents a significant realignment in the global economic landscape, with the epicenter of growth moving from the West to the East (Phakawa, 2015). This development sheds light on the potential role China could aspire to in the global economic arena and the possible frictions that might arise with the current hegemon, the United States.

The seeds of a new, or at least revised, economic system had already been laid, awaiting further development and revelation. This process was catalyzed by recent global events. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, the conflict in Ukraine, and the escalating climate crisis have all highlighted and accelerated certain underlying trends. Globalization, increasingly viewed as failing to yield equitable results, has sparked a demand for the establishment of new guidelines and a more inclusive, growth-oriented framework.

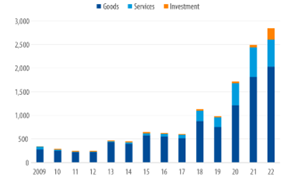

Furthermore, the strategic use of economic power and the growing belief that global interdependence could undermine national economies and hinder the pursuit of prosperity have gained widespread attention. For example, prioritizing the resilience of global value chains, even at the cost of efficiency, has emerged as a key focus for policymakers worldwide. Both developed and developing nations have become acutely sensitive to the potential exposition of their economies to external pressures and the risks of weaponization of foreign leverage and have taken, thereby, comprehensive steps to protect their economic sovereignty. This shift towards caution regarding globalization’s benefits has paved the way for an era dominated by nationalist policies and the extensive application of industrial strategies, often with distortive outcomes. A prominent example of this trend is the significant rise in trade protectionism observed since the COVID-19 pandemic began (Bolhuis, 2023). Moreover, the strategy of employing subsidies to bolster local businesses has seen a dramatic increase; the frequency of such measures has surged by 1.5 times, reaching unprecedented levels (Figure 1). Specifically, the number of subsidy announcements escalated from 760 in 2009 to approximately 3000 in 2021 (Rotunno & Ruta, 2024). This surge is particularly notable in the context of global trade alert announcements, where the proportion of subsidy-related actions jumped from 29% to 60% during the same period (Figure 2). The COVID-19 crisis intensified an already strong trend toward increased reliance on subsidies as a policy tool.

| Figure (1): Number of Subsidies and subsidy share in all Global Trade alert policies over time |

|

| Source : Rotunno & Ruta, 2024

|

| Figure (2): Number of trade restrictions imposed annually worldwide. |

|

| Source : Bolhuis, Chen & Kett (2023) |

In this new normal “permacrisis’ environment, where the economy does not surpass one shock before receiving a second, we are witnessing a strong comeback of industrial policy as a miracle cure for economic but also non-economic issues. If the economic rationale behind the use of industrial policy is addressing market and coordination failures, as well as the provision of public goods, recent crises have shed light on the need to use industrial policy for non-economic concerns, such as the interference of geopolitical conflicts in shaping delocalization and sourcing policies (Ait Ali et al., 2022). Correspondingly, sovereignty considerations have taken precedence over the pursuit of efficiency, generating, hence, some rent-seeking behaviors that may exacerbate the already existing market imperfections. Moreover, pushed to its extreme, a fierce use of industrial policy may result in an escalation of protectionist measures among global economies, wiping out all the benefits of free trade policies.

In this regard, industrial policy is presenting a multifaceted impact on economies with its “good,” “bad,” and “ugly” aspects. On the “good” side, it holds the potential to mitigate market failures, pave the way for a green economy, and reduce inequalities, addressing key areas where market mechanisms fall short. However, the “bad” elements surface when sovereignty concerns override efficiency objectives (Canuto et al, 2023), leading to rent-seeking behaviors, particularly in nations with weak governance. The “ugly” aspect reveals itself in the uncooperative and globally distortive nature of trade protectionism ingrained in industrial policy, risking a detrimental race to the bottom among countries. Critics argue that these downsides may render industrial policy’s remedy more harmful than the economic ailments it aims to cure, sparking a debate on its overall efficacy.

Recommendations:

Legitimizing the use of “distortive policies” at a certain scale and coverage

The increasing prominence of non-economic objectives as a motivation for adopting industrial policy mechanisms poses a major challenge to sustaining multilateral trade cooperation (Hoekman et al., 2023), particularly in the context of growing geopolitical fragmentation.

Evenett et al. (2023), using data for China, the European Union, and the United States, estimate that there is a 73.8% probability that a subsidy granted by a large economy for a specific sector is met with a subsidy for the same product in another large economy.

To date, no formal inventory of industrial policy measures has been collected by international organizations. The Global Trade Alert (GTA)[1] New Industrial Policy Observatory (NIPO) database is an alternative approach to filling this gap. After twelve months of collecting data, they have recorded 2,500 NIPs worldwide, out of which 71% are considered trade-distorting.

One of the most relevant findings of this initiative is that advanced economies (AEs) were more active than emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) in using industrial policy in 2023. Corporate subsidies have been the most common type of trade-distorting instrument (Evenett et al., 2024). Motivations related to climate change account for 28 percent.

Subsidies are the preferred instrument being used by AEs to cope with non-economic objectives. Considering that EMDEs have no fiscal capacity to deploy comparable amounts, subsidies should be a priority of the G20’s cooperation initiatives to face the challenges posed by this NIP wave.

Among the several non-economic objectives of NIP, climate change is a candidate for special attention since it involves a global externality (Bown, 2023). Even so, it does not mean that any instrument of industrial policy deployed with the motivation of mitigation or adaptation to climate change should be legitimized. There is a need for global limits to subsidy races, not least in the interest of lower-income economies that depend on large producers (Posen, 2023).

WTO regulations focus on disciplining the use of unilateral trade policy instruments and mitigating their distortive impacts on other member countries. The Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (SCM) introduced the concept of “serious prejudice” – meaning the economic harm resulting from the deployment of new subsidies affecting competition in third markets. The SCM Agreement regulates specific subsidies – those granted to specific sectors – considered actionable and prohibits subsidies contingent on export performance and local content.

The current wave of NIPs has incorporated elements incompatible with the SCM Agreement, such as those contingent on local content. Due to the WTO’s current fragility, the G20 members should set a cooperation mechanism to curb the distortions created by the surge of subsidies in NIPs.

The G20 should focus on green subsidies, recognizing that climate change is the only non-economic motivation for NIPs with a global impact. This initiative should involve setting ceilings for the amounts of subsidies granted and compensation mechanisms for the distorting effects these policies cause to third countries, especially on medium and low-income economies.

Setting the principle of “there is no free lunch”

To address the issue of setting ceilings for trade-distorting subsidies, the first step should be to improve data on subsidies. Although WTO members have committed to notifying implemented subsidies, most countries have been underreporting. International organizations such as the IMF, World Bank, and OECD have cooperated with the WTO to build a website providing information on agriculture subsidies, fossil fuels, fisheries, industrial sectors, and cross-sectoral and economy-wide activities (Hoekman et al, 2023). Merging these databases under the umbrella of a cooperation mechanism involving international institutions with the technical support of the WTO Secretariat (perhaps they could constitute an Advisory Technical Committee) could provide the necessary solid information base for the design of compensatory mechanisms as follows:

- Classify the subsidies according to their degree of potential harm to third countries, considering how trade-distortive they are. This could be done by adopting the model set in the WTO Agreement on Agriculture that labels subsidies as (i) trade-distorting (amber box), (ii) minimally trade-distorting (green box), and (iii) production-limiting programs (blue box).

- The G20 countries should agree to cap total spending on amber box subsidies while all countries should be allowed to provide de minimis levels of support. Limits could vary according to product sectors or supply chains, considering their contribution to climate change mitigation or adaptation objectives. The group could agree to create a list of green-box subsidies not subject to limits or compensation mechanisms. See Hillman and Munak (2024) for a similar proposal.

- Create a platform for dialogue and compensation negotiations with the technical support of international institutions. Building on the experience of the WTO consultation process called Specific Trade Concerns (STC) under the Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) and Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS) agreements, the G20 could create a platform where countries harmed by subsidies classified under the amber box would negotiate with implementing jurisdictions, replacing the WTO dispute settlement mechanism for a more cooperative approach. The result could be (i) the redesign of the subsidy program to eliminate its distorting features, (ii) compensation through non-discriminatory trade liberalization in products of interest of the exporting country, and (iii) engaging in countermeasures as a remedy. (See Hoekman et al, 2023, for a similar proposal).

- Contribute with a small proportion of the subsidies deployed for domestic production to an international fund that would finance the diffusion of green technologies to middle and low-income economies (See Posen, 2023).

Scenario of outcomes:

Unlike the main motivations of industrial policies of the last century, current industrial policies involve non-economic objectives, such as dealing with geopolitical conflicts, security concerns, the resilience of value chains to unforeseen shocks, access to medicines and equipment in the case of a pandemic, and, overlaying all these, climate change mitigation.

Another essential difference is that large economies are deploying vast amounts of subsidies to promote localization of industrial production, regardless of efficiency or productivity considerations. Emerging and least-developed economies, with smaller or no fiscal space to implement industrial policies, are already suffering the negative impacts of this NIP wave on their exports’ competitiveness or increased competition in their domestic markets with subsidized imports. This is a challenging scenario for low and middle-income economies.

Adopting the recommendations to legitimize the use of “distortive policies” within defined limits and to assert the principle that “there is no free lunch” would lead to a nuanced scenario of outcomes for G20 countries and the global economy. On the one hand, by establishing a framework that legitimizes certain trade-distorting subsidies, particularly for climate change mitigation, the G20 could foster innovation and green technology adoption. This would create a more sustainable global economy, aligning economic policies with environmental objectives. Advanced economies would be able to continue supporting their strategic industries while emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) receive targeted assistance, narrowing the development gap and potentially leading to a more equitable global economic landscape.

The creation of ceilings and compensation mechanisms, while intended to curb the excesses of subsidy races, might inadvertently solidify the advantages of wealthier nations that can afford to allocate significant resources towards “green box” subsidies. Furthermore, the reliance on a cooperative mechanism to address disputes could strain international relations, especially if countries perceive the negotiations as unfair or biased.

In essence, the proposed initiatives aim to balance the urgent need for environmental action with the realities of economic competition and national interests.

References:

Ait Ali, A., M. Arbouch, and O. Canuto. 2022. “Pandemic, War, and Global Value Chains.” Policy Center for the New South. Policy Paper.

Blanchet, Thomas, Lucas Chancel, and Armory Gethin. 2019. “How Unequal is Europe? Evidence from Distributional National Accounts, 1980–2017.” Working Paper 2019/06. World Inequality Lab: World Inequality Database.

Bolhuis, Chen, and Kett. 2023. “The High Cost of Global Economic Fragmentation.” IMF.

Bown, Chad P. 2023. “Modern Industrial Policy and the WTO.” PIIE Working Paper 23–15. Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Canuto, O., M. Arbouch, P. Zhang, and A. Ait Ali. 2023. “GVCs, Resilience, and Efficiency Considerations: Improving Trade and Industrial Policy Design and Coordination.” T20 India Policy Brief.

Park, Donghyn, Arief RamaYandi, and Kwanho Shin. 2013. “Why did Asia fare better during the global financial crisis than during the Asian financial crisis.”

Evenett, Simon, Adam Jakubik, Fernando Martín, and Michele Ruta. 2024. “The Return of Industrial Policy in Data.” International Monetary Fund. WP/24/1.

Hillman, Jennifer, and Inu Manak. 2023. “Rethinking International Rules on Subsidies.” Council Special Report No. 96. September 2023. Council on Foreign Relations.

Hoekman, Bernard, Petros C. Mavroidis, and Douglas R. Nelson. 2023. “Non-economic Objectives, Globalisation and Multilateral Trade Cooperation.” CEPR London.

IMF. 2018. “The Global Recovery 10 Years after the 2008 Financial Meltdown.” World Economic Outlook.

Littler, Graeme B. “Global-Productivity-Chapter-1.” World Bank. July 2020.

Jeasakul, Phakawa. 2015. “Is Asia Still Resilient?” IMF.

Posen, Adam. 2023. “Re-globazing subsidies for a sooner, fairer green future.” Opinion Piece. In World Trade Report 2023. Re-globalization for a secure, inclusive and sustainable future. World Trade Organization. Geneva.

Qureshi, Zia. 2023. “Rising inequality: A major issue of our time.” Brookings. May 16, 2023.

[1] See https://www.globaltradealert.org/about for a description of the initiative and the content of the database.