Policy Center for the New South, PB – 32/23

This study analyzes the challenges related to the fiscal space in Africa and examines the impact of BEPS on African economies. We examine the factors that exacerbate BEPS in the region, including the absence of relevant international tax laws, the dynamics of tax treaty negotiations, and limited tax administration capacity. We will also assess the negative impact of BEPS in Africa and discuss current initiatives to address BEPS in Africa, such as those proposed by the OECD. Finally, we discuss the challenges and offer policy recommendations for increasing fiscal space and reducing BEPS in Africa.

Introduction

Fiscal space, defined as “the availability of budgetary room that allows a government to provide resources for a desired purpose without any prejudice to the sustainability of a government’s financial position” (Heller, 2005), is a key issue for African countries. This concept is of particular importance to African nations as they strive to address pressing development needs, including provision of infrastructure, social services, and environmental protection. Despite these ambitions, African countries face a unique set of challenges, including limited tax revenues, dependence on external aid, and the volatility of commodity prices. A thorough understanding of the complexities surrounding fiscal space is essential for African countries to navigate the complex terrain of sustainable development, and to move their societies toward prosperity and resilience.

In addition, fiscal space in Africa is affected by another critical challenge: base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS). This complex phenomenon consists of aggressive tax practices used by multinational companies to artificially reduce their tax bases and shift profits to low-tax jurisdictions, resulting in a loss of tax revenue for African countries and a distortion of economic competition.

While BEPS is a global issue, developing countries, particularly in Africa, are affected disproportionately because of their increased reliance on corporate income taxes to finance their development policies. In fact, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Africa’s corporate tax-to-GDP ratio[1] stood at 2.9% in 2020. BEPS also creates a sense of tax injustice, undermines tax morale, and reduces fair competition between domestic and foreign companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises.

This study analyzes the challenges related to the fiscal space in Africa and examines the impact of BEPS on African economies. We examine the factors that exacerbate BEPS in the region, including the absence of relevant international tax laws, the dynamics of tax treaty negotiations, and limited tax administration capacity. We also assess the negative impact of BEPS in Africa and discuss current initiatives to address BEPS in Africa, such as those proposed by the OECD. Finally, we discuss the challenges and make policy recommendations for increasing fiscal space and reducing BEPS in Africa.

This study aims to contribute to a better understanding of the economic and fiscal challenges faced by African countries with respect to fiscal space and BEPS. By understanding the issues and potential solutions, we hope to stimulate a constructive and informed debate to support sustainable development efforts in Africa.

I. Conceptual framework

1.1 Fiscal space

Fiscal space, as defined by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), refers to “the room to undertake discretionary fiscal policy relative to existing plans without endangering market access and debt sustainability” (IMF, 2018a). For example, the desired objective might be to increase public spending in social or productive sectors, or to reduce taxes to stimulate demand or supply.

There is no single, universal definition of fiscal space. Various authors have proposed alternative definitions according to their analytical or normative perspectives. For example, Ostry et al (2010) defined fiscal space as “the difference between the current level of public debt and the debt limit implied by the country’s historical record of fiscal adjustment”. Perotti (2007) considered the notion of fiscal space as an alternative way of expressing a sovereign’s intertemporal budget constraints. Wyplosz (2020) viewed fiscal space as a measure of a government’s ability to pursue expansionary fiscal policies without creating long-term concerns. He argued that this notion cannot be encapsulated in a single numerical value, but rather encompasses a range of numbers that depend on explicitly constructed future assumptions tailored to policymaking.

Furthermore, Roy et al (2007) defined fiscal space as the financial resources available to a government as a result of concrete policies that enhance resource mobilization. These policies are coupled with reforms that are essential to create a supportive governance, institutional, and economic environment. These combined efforts are aimed at effectively achieving specific development objectives.

According to Botev et al (2016), several approaches can be used to measure fiscal space.

In the market access risk approach, fiscal space is calculated as the distance between the current level of public debt and the estimated limit beyond which the government loses access to financial markets and cannot service its debt. This approach depends on assumptions about risk-free interest rates and potential GDP growth, the magnitude of shocks to the economy, the country’s fiscal history, and its fiscal response to rising debt (Ghosh et al, 2013; Fournier and Fall, 2015).

The sovereign default risk approach, meanwhile, assesses a government’s default risk by evaluating the long-term sustainability of its public finances. This approach uses an economic model that incorporates economic shocks and long-term projections of government spending and revenues. This approach does not provide a maximum level of debt, but rather a probability of default for each level of debt. This probability is calculated using the present value of future maximum primary balances obtained by maximizing tax revenues and minimizing public expenditures (Bi, 2011; Bi and Leeper, 2013).

Finally, the long-term sustainability approach examines whether the government can stabilize its debt-to-GDP ratio at its current level or at a target level, depending on its projections for public spending and revenues. If the interest rate is lower than the growth rate, the government can run permanent deficits without increasing its debt. If the interest rate is higher than the growth rate, the government needs a certain level of taxation to stabilize its debt. Fiscal space is then the difference between that level of taxation and the current level of taxation. This approach does not take economic shocks into account (Blanchard et al, 1990).

1.2 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS)

BEPS is the phenomenon of use by multinational companies of aggressive tax strategies to artificially reduce their tax bases and shift their profits to low-tax jurisdictions. BEPS results in a loss of tax revenue for the countries where multinationals operate, and a distortion of competition between domestic and foreign companies.

The concept of BEPS has been popularized by the OECD, which in 2013 in cooperation with the G20 launched a project to combat BEPS. The OECD identified 15 actions to combat BEPS, covering legal, economic, and administrative aspects of international tax policy (OECD, 2015). These actions aim to establish a single set of international tax rules to end the erosion of tax bases and the artificial shifting of profits to certain jurisdictions for tax avoidance purposes.

The concept of BEPS has also been taken up by other international organizations, including the United Nations, the IMF, the World Bank Group, and the African Tax Administration Forum (ATAF), which have developed their own analyses and recommendations on BEPS, taking into account the specificities of developing countries and African countries in particular (UN, 2019; IMF, 2014; World Bank Group, 2016; ATAF, 2017).

Measuring and monitoring BEPS is not an easy task, as it involves complex and multidimensional phenomena that are not directly observable. There are also significant limitations in the availability and quality of data on BEPS, and methodological difficulties in isolating the effect of BEPS from other factors that influence the revenues and activities of multinational enterprises. As a result, there is no single, universal measure of BEPS, but rather a range of methods and indicators that need to be used with caution and transparency.

The OECD in 2015 proposed a set of indicators to measure BEPS, based on aggregate data on the revenues and activities of multinational enterprises. It set out six BEPS indicators, which are statistical measures designed to show the existence and extent of BEPS based on different data sources. These indicators are grouped into five categories according to the type of BEPS strategy they are intended to capture:

– The disconnect between financial and real activity: this assesses the extent to which foreign direct investment (FDI) differs from the size of a country’s economy as measured by gross domestic product (GDP)[2]. This gap may indicate that FDI is being used to shift profits to low-tax countries rather than to finance productive activities. In other words, this indicator helps determine whether companies are using FDI to shift their profits to countries where taxes are very low, rather than actually investing in activities that would stimulate the local economy.

– Profit rate differentials within large multinational enterprises (MNEs): This involves comparing the profit rates of MNEs with their effective tax rates or with the average profit rates of all MNEs, which may reveal anomalous deviations related to BEPS.

– Effective tax rate differentials between MNEs and comparable non-MNEs: this involves comparing the effective tax rates of MNE subsidiaries with those of non-MNEs with similar characteristics, which may show that MNEs enjoy an undue tax advantage over their local competitors.

– Profit shifting through intangibles: This involves measuring the ratio of royalty income to research and development (R&D) expenditures in certain countries, which may indicate that intangible assets are artificially located in low-tax jurisdictions without a link to value creation.

– Profit transfer through interest: this measures the ratio of interest expenses to income of MNE subsidiaries in high-tax countries, which may indicate that MNEs are using excessive debt to reduce their tax bases.

The OECD (2015) explained that these indicators are not perfect and are affected by the limitations of the available data. It also stressed that they must be interpreted with caution and complemented by other approaches.

II. The evolution of fiscal space and BEPS in African countries

2.1 The fiscal space

Fiscal space in African countries is central to their economic and social development. It is essential if African countries are to meet the development needs of their populations, particularly in terms of infrastructure, social services, and environmental protection. However, the fiscal space of African economies is constrained by several factors, including low tax revenues, dependence on foreign aid, volatile commodity prices, climatic and health shocks, and the risk of over-indebtedness.

A World Bank study examined the evolution of fiscal space in sub-Saharan Africa. It used 28 indicators related to public debt sustainability, public sector balance sheet composition, external and private debt, and market perceptions. (Calderon Cesar et al; 2018). It found that fiscal space increased between 2000 and 2008 as a result of economic growth, debt relief, and improved public financial management, allowing countries in the region to pursue countercyclical policies in the face of the 2008-09 global financial crisis. It also showed that fiscal space shrank between 2009 and 2015 because of falling commodity prices, rising public debt, and less access to financial markets, which limited the ability of countries in the region to cope with economic shocks and development needs.

Since 2015, fiscal space in Africa has been affected by several major events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, falling oil prices, armed conflicts, and humanitarian crises. These events had contrasting effects on public revenues and expenditures and on debt sustainability in African countries.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to an unprecedented economic recession in Africa, resulting in a 1.8% decline in real GDP in 2020. The health crisis resulted in reduced tax revenues, particularly from taxes on goods and services, personal and corporate income taxes, and customs duties. According to the OECD, the average tax-to-GDP ratio in sub-Saharan Africa fell from 16.6% in 2019 to 16% in 2020. At the same time, the pandemic required increased public spending to finance health, social, and economic measures to mitigate the impact of the crisis on populations and businesses. The average budget deficit in Africa increased from 3.5% of GDP in 2019 to 5.6% of GDP in 2020. Together, these dynamics have reduced the fiscal capacity of African countries and increased their dependence on external financial assistance.

The decline in oil prices in 2020 has also affected the fiscal space of oil-exporting African countries, including Algeria, Angola, Gabon, Nigeria, and the Republic of Congo. These countries have seen their export earnings and oil-related tax revenues fall sharply. According to the World Bank, the average price of a barrel of crude oil fell from $61 in 2019 to $41 in 2020. This decline has had a negative impact on current account and fiscal balances in these countries, and on their ability to repay their external debts.

Armed conflicts and humanitarian crises have also affected the fiscal space of some African countries, particularly those in the Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali, Niger) and the Horn of Africa (Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan). These situations have led to a disruption of economic activity, a deterioration of public infrastructure, a reduction in the tax base, and an increase in humanitarian needs. According to the United Nations (2022), more than 110 million people in Africa are in need of humanitarian assistance.

Another major event affecting the fiscal space of African countries in 2022 was the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. This conflict has affected world prices for oil, wheat, and sunflower, for which Africa is heavily dependent on imports. Russia and Ukraine are among the main suppliers of these commodities to Africa. According to FERDI (2022)[3], the Russian-Ukrainian conflict poses a major risk to food and energy security in Africa. A prolonged conflict could further jeopardize wheat exports to the region and further drive-up prices. In addition, the crisis has led to a rise in oil prices, which have reached their highest level since 2014. This increase has had a negative impact on net oil-importing African countries, which have faced rising energy bills and deteriorating trade balances.

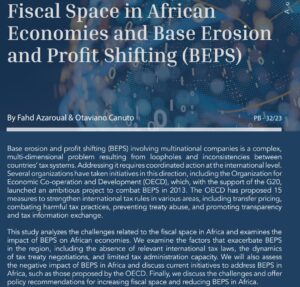

Figure 1 shows a general measure of fiscal space for oil-exporting African countries, other resource-intensive African countries, low-resource-intensive African countries, and tourism-dependent African countries for 2006, 2009, and 2019. From an operational point of view, fiscal space is defined as the inverse of the number of fiscal years required to fully repay public debt (Aizenman and Jinjarak, 2010).

The calculation of this indicator[4] requires information on outstanding public debt and an approximation of the de facto tax base of the economy. Kose et al (2017) used the general government gross debt position as an indicator of public debt. The de facto tax base, on the other hand, is measured by average tax revenue over a number of years; this smoothes out cyclical fluctuations in the tax base and hence in tax revenue.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the number of fiscal years needed to fully repay public debt for four groups of African countries, and the African average between 2006 and 2019. The higher the number, the smaller the fiscal space, as it implies that the country has a high level of debt relative to its ability to raise taxes.

Figure 1 shows the evolution of the number of fiscal years needed to fully repay public debt for four groups of African countries, and the African average between 2006 and 2019. The higher the number, the smaller the fiscal space, as it implies that the country has a high level of debt relative to its ability to raise taxes.

It can be observed that among the four groups, oil-exporting African countries need the most fiscal years, indicating that they have the least fiscal space. This number increased between 2006 and 2019, from 5.95 to 6.65 years, suggesting that these countries saw their fiscal situations deteriorate over this period, probably because of lower oil prices and reduced export revenues. Indeed, these countries are heavily dependent on oil revenues to finance their public spending and repay their debts. When oil prices fall, they must either cut spending, raise taxes, or borrow more, which reduces their fiscal space.

The other resource-intensive African countries need the fewest fiscal years among the four groups, indicating that they have the greatest fiscal space. This number increased from 2.29 to 3.46 years between 2006 and 2012 and stabilized at around 3 years between 2012 and 2019. This suggests that these countries experienced some deterioration in their fiscal positions between 2006 and 2012, but managed to stabilize or improve their positions between 2012 and 2019. These countries are also dependent on natural resource revenues to finance public spending and debt repayment, but are less exposed to oil–price fluctuations than oil-exporting countries. They also enjoyed stronger and more diversified economic growth than oil-exporting countries over this period.

Low resource-intensive African countries need the second lowest number of fiscal years to repay debt, among the four groups, indicating that they have relatively more fiscal space. This number decreased from 3.38 to 2.74 years between 2006 and 2012, and then increased to 4.15 years between 2012 and 2019. This suggests that these countries experienced an improvement in their fiscal positions between 2006 and 2012, but a deterioration between 2012 and 2019. These countries are less dependent on natural resource revenues to finance public spending and repay debt, but they are more vulnerable to external shocks such as exchange–rate fluctuations, changes in the terms of trade, or natural disasters. They were also affected by weak global demand and slowing regional growth during this period.

Tourism-dependent African countries need the second highest number of fiscal years among the four groups, indicating that they have relatively little fiscal space. This number decreased from 4 to 3.4 years between 2006 and 2012, and then increased to 4.84 years between 2012 and 2019. This suggests that these countries experienced an improvement in their fiscal positions between 2006 and 2012, but a deterioration between 2012 and 2019. These countries are heavily dependent on tourism revenues to finance public spending and repay debt, but they are also exposed to fluctuations in tourism demand, which can be affected by factors such as security, political stability, competitiveness, or the COVID-19 pandemic. They also suffered from weak global growth and reduced external financial flows during this period.

The average for Africa shows that the number of fiscal years required to fully repay public debt remained relatively stable between 2006 and 2019, increasing from 4.03 to 4.73 years. This suggests that the continent’s overall fiscal space has not changed much over this period, but masks significant differences between different groups of countries.

2.2 BEPS in Africa

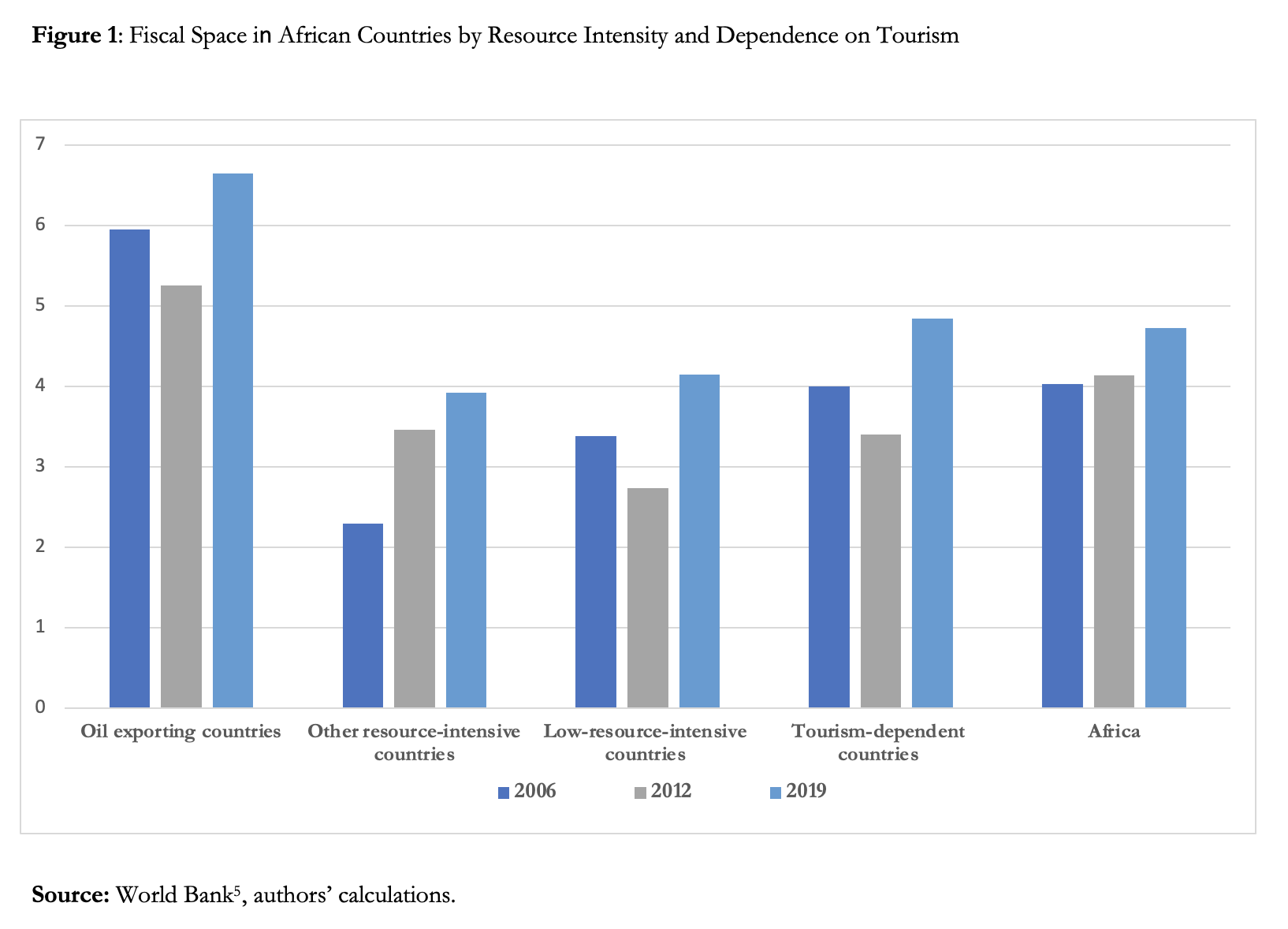

According to the OECD, BEPS practices cost governments between $100 billion and $240 billion a year in lost revenue, or between 4% and 10% of global corporate tax revenue. Because developing countries are more dependent on corporate taxes, they suffer disproportionately from BEPS. In fact, not all countries are equally affected by BEPS practices. The share of corporate income tax in total tax revenue is much higher in developing countries than in OECD countries: for example, 58% in India, 66% in Malaysia, 52% in Indonesia, and 34% in Morocco, compared with 9% in France and the UK (Figure 2). As developing countries are more dependent on corporate income tax, their tax revenues have continued to suffer disproportionately from BEPS practices, hindering sustainable development (OECD, 2021).

2.2.1 Negative Effects of BEPS in Africa

2.2.1 Negative Effects of BEPS in Africa

In Africa, this practice has become a major concern as it results in the loss of critical tax revenues needed to finance public infrastructure and economic development. There is no precise data on the extent of BEPS in Africa due to the lack of available and comparable information on the activities and profits of multinational enterprises. However, there are some studies and reports that have attempted to estimate BEPS-related losses for Africa. For example, according to the UN Economic Development in Africa Report 2020, African countries lose an estimated $88.6 billion each year, equivalent to 3.7% of the continent’s economic output, in illicit capital flight, and about 2.7% of their GDP due to BEPS (United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, 2019). Some estimates put the losses due to BEPS at between 1% and 6% of GDP (Moore et al, 2018).

In fact, African countries have been victims of the BEPS phenomenon for decades, with their residents transferring funds to developed countries and tax havens. This loss of tax revenue leads to a critical underfunding of public investments needed for economic growth, affecting the financing of infrastructure including roads, hospitals, and schools. BEPS undermines the integrity of the tax system by creating a sense of tax injustice, discouraging tax compliance, and reducing voluntary compliance by all taxpayers. It also harms competition by giving multinational companies a competitive advantage over domestic companies, especially small and medium enterprises (Wanyana Oguttu, 2016).

Although some MNEs claim to respect tax laws in Africa by complying with minimum rules rather than optimizing their taxation, there is evidence of tax evasion that weakens the tax bases of African countries. For example, according to an IMF study, sub-Saharan African countries lose between $450 million and $730 million in corporate tax revenue annually due to profit shifting by multinational mining companies. (Giorgia Albertin et al ,2021). Another study found that mineral and oil extraction companies are responsible for much of the tax evasion in Sub-Saharan Africa, accounting for total annual losses of up to 6 percent of African GDP.(Borgen project ,2019)

Although there are indications, such as those mentioned above, that BEPS is widespread in Africa, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the actual extent of BEPS. There are no accurate estimates of the amount of profits transferred (Fuest et al, 2013).

2.2.2 Factors Contributing to BEPS in Africa

Several factors contribute to the proliferation of BEPS in Africa. First, the lack of relevant international tax laws or a clear understanding of how they work limits the ability of African countries to combat BEPS. Historically, these countries have prioritized taxing the domestic income of resident taxpayers, which has delayed the implementation of international tax laws in Africa. However, with the increasing internationalization of economic relations, many African countries have become aware of the need to develop international tax laws to counter BEPS (Wanyana Oguttu, 2016).

Another complicating factor is the dynamics of tax–treaty negotiations. Many African countries have signed few tax treaties, and some have done so primarily as a political gesture, rather than because of significant capital flows from the developed countries concerned (OECD, 2013b). Some countries even avoided concluding tax treaties in order to preserve their tax revenues. However, with increasing openness to foreign investors, many African countries have expanded their networks of tax treaties. Unfortunately, in the absence of anti-avoidance measures, these treaties can be exploited, leading to cases of BEPS. Indeed, developing countries often find it difficult to negotiate favorable tax treaties because of a lack of expertise and experience. Capacity–building initiatives are needed to strengthen their role in the fight against international tax evasion (Wanyana Oguttu, 2016).

The UN (2013) noted that: “Developing countries, especially the least developed ones, often lack the necessary expertise and experience to efficiently interpret and administer tax treaties. This may result in difficult, time-consuming and, in a worst case scenario, ineffective application of tax treaties. Moreover, skills gaps in the interpretation and administration of existing tax treaties may jeopardize developing countries’ capacity to be effective treaty partners, especially as it relates to cooperation in combating international tax evasion. There is a clear need for capacity-building initiatives, which would strengthen the skills of the relevant officials in developing countries in the tax area and, thus, contribute to further developing their role in supporting the global efforts aimed at improving the investment climate and effectively curbing international tax evasion”.

Finally, the limited tax administration capacity of African countries is a major challenge in curbing BEPS. To combat these practices effectively, African countries need to strengthen their administrative capacity by hiring competent tax officials and training them on complex BEPS issues. This also requires technological advances to facilitate the automatic exchange of tax information and strengthen revenue collection (Wanyana Oguttu, 2016)

2.2.3 Africa Against BEPS

African countries are becoming increasingly aware of the problem of BEPS and its negative impact on the continent’s development. To combat this phenomenon, many countries have strengthened their tax legislation, tax administrations, and regional and international tax cooperation. Morocco, for example, has introduced anti-abuse rules, transfer pricing rules and country-by-country reporting requirements for multinational groups. Senegal adopted a tax transparency law to prevent tax evasion, strengthen tax administration and improve revenue collection, South Africa strengthened its tax treaty network to prevent treaty abuse and improve information exchange with other countries and Ghana has introduced a series of tax reforms to improve revenue collection and prevent tax evasion. These include modernizing tax filing and payment systems, introducing electronic invoicing for businesses, and strengthening tax controls for multinational companies operating in the country.

At the international level, Africa is actively involved in the process of reforming the global tax system led by the OECD and the G20. Some 27 African countries are members of the BEPS Inclusive Framework, which implements and monitors the 15 Actions of the BEPS project. Africa is also represented in the Inclusive Framework Steering Group, which oversees the technical and policy work on BEPS.

In July 2021, more than 130 countries and jurisdictions, including many African countries, signed up to a new two-pillar plan to reform global tax rules and ensure that multinational companies pay their fair share of taxes wherever they operate. The first pillar of the Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) agreement (Pillar One) aims to ensure a fairer distribution of profits and tax claims between countries for the largest multinationals, including digital companies, while the second pillar introduces a global minimum corporate tax rate that will protect countries’ tax bases and put a floor under tax competition between jurisdictions.

Today, many African countries face challenges in taxing highly digitized businesses due to prevailing international tax rules. These rules assign the right to tax only to the country where non-resident companies establish a tangible physical presence. Anticipating that Pillar One will see taxing rights to more than $100 billion worth of multinational profits redistributed to market jurisdictions each year, ATAF believes that these rules could serve as effective mechanisms to redress the prevailing imbalance in the allocation of taxing rights between residence and source countries. Furthermore, the introduction of a global minimum corporate tax rate of 15% through the second pillar is seen as an important step to mitigate the race to the bottom and counter other harmful tax practices (WEF 2021).

2.2.4 Challenges and Risks of BEPS Measures for African Countries

While the BEPS measures are beneficial for developed countries, which will be able to recover some of the tax revenue lost to tax avoidance they may pose challenges and risks for developing countries, such as those in Africa. These challenges and risks relate to the complexity of the measures, the capacity of tax administrations to apply them, and the potential impact on the attractiveness of African countries for foreign investment.

The BEPS measures are based on a set of 15 actions covering various aspects of international taxation, including determining the place of taxation, transfer pricing, tax transparency, combating harmful tax practices, and resolving tax disputes. These measures include legislative, regulatory, and administrative changes, as well as the establishment of cooperation and information exchange mechanisms between tax authorities in different countries.

These measures are therefore highly complex and technical, which can be challenging for African countries, which often have less–developed and less–efficient tax systems than those in developed countries. African countries may lack the technical expertise, human and financial resources, or IT infrastructure to implement the BEPS measures. They may also have difficulty coordinating with other countries, particularly those that are not part of the BEPS project or that have divergent interests.

BEPS measures also require increased capacity on the part of tax administrations to monitor and audit the tax returns of multinational enterprises and to resolve any disputes or litigation that may arise. Tax administrations in African countries often face problems of corruption and weak institutional capacity. These problems can limit the ability of tax administrations to effectively apply BEPS measures and thus collect the tax revenues to which they are entitled.

BEPS measures may also have a negative impact on the attractiveness of African countries for foreign investment, which is essential for their economic and social development. Indeed, multinational companies may be deterred from investing in countries that have introduced complex tax regimes that increase their compliance costs and double taxation risks.

Multinational companies may also prefer to invest in countries that offer them specific tax benefits, such as tax exemptions or reductions, or free trade zones. African countries may therefore find themselves in a situation of unfavorable tax competition with countries that have not adopted BEPS measures or have adopted them selectively.

III.Policy Recommendations

To strengthen the fiscal space of African countries and effectively combat BEPS, a number of policy and strategic measures can be taken. First, it is essential that African governments promote fair and progressive taxation. This means adopting tax policies that ensure a fair distribution of the tax burden between high-income and low-income companies and individuals. By adopting progressive tax rates, African countries can ensure that those with the means contribute proportionately more to the financing of public infrastructure and social services, thus creating more fiscal space for investment in economic and social development.

Second, promoting tax transparency is a key element in the fight against BEPS. African countries should require greater disclosure of financial information from companies, particularly with respect to profits earned, taxes paid, and activities carried out in each jurisdiction. By making this information available, African tax authorities will be able to better understand the activities of multinational companies operating on their territory, identify BEPS risks, and take appropriate measures to prevent tax evasion.

Third, it is crucial to strengthen regional and international cooperation among African countries in the fight against tax evasion and BEPS. To this end, mechanisms for automatic exchange of tax information among African countries and with other jurisdictions are needed to more effectively detect tax–evasion practices. In addition, the creation of regional forums for discussion and exchange on tax issues will facilitate the sharing of best practices and strengthen the administrative capacity of African countries in this fight. On the other hand, it is equally important that African countries strengthen their international cooperation by actively participating in global initiatives to combat tax evasion, in particular by committing to the OECD’s comprehensive framework on BEPS. This will enable them to play an active role in global tax discussions and reforms and ensure a fair distribution of taxing rights between countries. International cooperation is essential to address cross-border tax-avoidance practices, which can have a significant negative impact on the fiscal space of African countries.

Finally, African countries need to strengthen the capacity of their tax administrations to deal with BEPS. This means investing in training and capacity building for tax officials to better understand and detect tax evasion practices. It is also essential to take advantage of technological advances to facilitate the automatic exchange of tax information and strengthen revenue collection. By strengthening their administrative capacity, African countries will be able to better control and verify the tax declarations of multinational companies, effectively combat BEPS, and recover the tax revenues that are rightfully theirs.

Bibliography

ActionAid (2012) “Calling Time: Why SABMiller should stop dodging taxes in Africa”.Report

Aizenman, J., & Jinjarak, Y. (2010). “De facto Fiscal Space and Fiscal Stimulus: Definition and Assessment” (No. w16539). National Bureau of Economic Research.

Albertin, G., Devlin, D., & Yontcheva, B. (2021). ” Countering Tax Avoidance in Sub-Saharan Africa’s Mining Sector. ” Fonds Monétaire International.

Bi, H. (2011). “Sovereign Default Risk Premia, Fiscal and Fiscal Policy.” Bank of Canada Working Paper, 2013-27, August, Ottawa.

Bi, H. and E. M. Leeper (2013). “Analysing Fiscal Sustainability.” Bank of Canada Working Paper, 2011- 10, August, Ottawa.

Blanchard, O. et al. (1990). “The Sustainability of Fiscal Policy: New Answers to an Old Question.” OECD Economic Studies, No. 15, Autumn, Paris.

Botev, J., J. Fournier, and A. Mourougane (2016). “A Re-assessment of Fiscal Space in OECD Countries.” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, No. 1352, OECD Publishing, Paris.

Calderon, Cesar; Chuhan-Pole, Punam; Some, Yirbehogre Modeste. (2018). ” Assessing Fiscal Space in Sub-Saharan Africa”. Policy Research

Fuest, Spengel, Finke, Heckemeyer & Nusser (2013). “Profit shifting and aggressive tax planning by multinational firms: issues and options for reform.” Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation Discussion Paper No 13–078.

Ghosh, A. R., et al. (2013). “Fiscal Fatigue, Fiscal Space and Debt Sustainability in Advanced Economies.” Economic Journal, Vol. 123, pp. 4-30.

Gourdon, J., & de Ubeda, A.-A. (2022). Conflit Russie – Ukraine : quelles conséquences sur les économies africaines ? Fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international.

Heller, P. (2005). “Back to Basics – Fiscal Space: What It Is and How to Get It.” Finance & Development, 42(2). IMF.

IMF, (2018a). Assessing Fiscal Space: An Update and Stocktaking. IMF Policy Paper, April 11.

IMF. (2014). “Spillovers in International Corporate Taxation.” Policy paper.

Kose et al. (2017). “A Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space”. Policy research working paper ,World Bank .

Moore, M., W. Prichard and O.-H. Fjeldstad. (2018). “Taxing Africa: Coercion, Reform and Development.” London: Zed Press and the International Africa Institute.

Nations Unies. (2022). “ L’inquiétude des « mégacrises » mondiales domine l’ouverture de la session de l’ECOSOC sur les affaires humanitaires. “ UN Press

Oguttu, A. W. (2016). “Tax Base Erosion and Profit Shifting in Africa – Part 1: Africa’s Response to the OECD BEPS Action Plan” (ICTD Working Paper 54). International Centre for Tax and Development.

OECD (2013b). “Action Plan on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting.” Paris: OECD Publishing.

OECD (2014a). “The BEPS Project and Developing Countries: from Consultation to Participation.”

OECD (2015). “Measuring and Monitoring BEPS, Action 11 – 2015 Final Report, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project.” OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD. (2021). ” Developing countries more at risk of lost corporate tax revenues. “

Ostry, J. D., Ghosh, A. R., Kim, J. I., & Qureshi, M. S. (2010). Fiscal Space. IMF Staff Position Note SPN/10/11. International Monetary Fund1.

Perotti, R. (2007). “Fiscal Policy In Developing Countries: A Framework And Some Questions.” World Bank.

Forum mondial sur la transparence et l’échange de renseignements à des fins fiscales. (2023). “Transparence fiscale en Afrique 2023: Rapport de progrès de l’Initiative Afrique.” OCDE.

Forum mondial sur la transparence et l’échange de renseignements à des fins fiscales. (2021). “Transparence fiscale en Afrique 2021 : Rapport de progrès de l’Initiative Afrique. “OCDE.

Roy, R., Heuty, A., & Letouzé, E. (2007). “Fiscal Space for What? Analytical Issues from a Human Development Perspective.” United Nations Development Programme.

The Borden project.(2019). “Tax Evasion in sub-saharan africa”. Blog

United Nations (2013). “Handbook on Selected Issues in Administration of Double Tax Treaties for Developing Countries.” New York: United Nations Publications.

United Nations (2015). “Outcome document of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development: Addis Ababa Action Agenda (13 to 16 July 2015).”

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (2019). “Chapter 6: Multinational corporations, tax avoidance and evasion and natural resources management.”

United Nations. (2019). ” United Nations Manual for the Negotiation of Bilateral Tax Treaties between Developed and Developing Countries “. Department of Economic and Social Affairs

United Nations. (2020). “Tackling Illicit Financial Flows for Sustainable Development in Africa”. Economic development in Report 2020

WEF. (2021). “How African countries can benefit from the plan to reform global tax.”

World bank. (2016). “Rapport Annuel 2016. ” Report

Wyplosz, Charles.(2020). “What’s Wrong with Fiscal Space? ” (February 2020). CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14431

[1] Corporate income, profit, and capital gains taxes.

[2] This indicator compares the amount of FDI in a country with the size of the country’s economy (GDP).

If the FDI/GDP ratio is significantly high, this could indicate that companies are using FDI to transfer profits to low-tax jurisdictions rather than for productive activities at national level. The indicator calculates this ratio for countries with high FDI/GDP ratios and compares it with the same ratio for other countries. This helps us to understand whether there is an imbalance between financial investment and real economic activity.

[3] Fondation pour les études et recherches sur le développement international.

[4] The formula for this indicator is as follows: Fiscal space = General government gross debt/Average tax revenues.

[5] A Cross-Country Database of Fiscal Space: https://www.worldbank.org/en/research/brief/fiscal-space.