Policy Center for the New South

Policy Paper PP-08-24, May 2024

Otaviano Canuto, Senior Fellow at the Policy Center for the New South

Sabrine Emran, Economist at the Policy Center for the New South

Badr Mandri, Economist at the Policy Center for the New South

“Commodities, are an object, a thing, which through its qualities satisfies human needs, of whatever kinds.” Karl Marx

Introduction:

Africa is full of examples of why commodities should be at the heart of the continent’s strategic choices. From minerals to agricultural and energy commodities, the continent’s resource wealth gives it the leverage to use its commodities to drive progress and prosperity. However, as we have already seen with the Dutch Disease, [1]the misuse or misappropriation of resources, especially commodities, can more often than not lead to catastrophic rather than positive outcomes. The financialization of commodities was introduced to the world as early as the 19th century and has been controversial in terms of bringing positive results and fuelling additional inflation. However, one thing is for sure, the financialization of commodities is worth exploring and there have been numerous examples of exploration in both developed and developing countries. Several African countries have already explored the financialization of agricultural commodities, but challenges such as lack of liquidity and financial market readiness have emerged as key issues that need to be addressed in order to decide on the maturity of the market for the eventual financialization of commodities. In this paper, we examine the definitions in the literature for the positive and negative aspects of commodity Financialisation, how financialized commodity markets have emerged around the world, examples from the African continent, and finally best practices and lessons learned on how best to prepare for commodity financialization and harness its potential positive outcomes.

- Commodities financialization: between vices and virtues

Commodities’ definition could at sight seem simplistic, and obvious. However, as K. Marx already highlighted it in the 19th century, “Commodity appears trivial. But analysis brings out that it is a very strange thing, abounding in metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties.”

The aftermath of commodities financialization through literature evidence

Swelling market inefficiency has been considered one of the most notable limits addressed in commodities financialization. The efficiency is argued through manipulating market liquidity. Among the supportive arguments lays the non-commercial speculators’ carry-out of entering both long and short positions, in contrast to only entering long positions for hedging against a real risk, grasped in the commodity risk mitigation. Short selling is thus engaged when investors believe that a stock price is overvalued and will eventually not provide the expected return, given the asset’s unmatching market value and actual value.

From a market integrity [2]point of view, it is considered that Over The Counter (OTC) derivatives [3] enhance excessive speculation in essential food and energy commodities, contributing eventually to an increase in volatility. This draws a link between the index speculation and the volatility increase that was beneficial for the non-commercial speculators[4], but harmful for the US economy as well as the society in a whole (BetterMarkets, 2023).

Similarly, during soaring prices periods, regulators argue that market prices could be stabilized by limiting the short-selling activity on markets. In March 2020, Italy, Spain, France, and Belgium, stopped the short selling of the listed stock in their markets, believing that the practice is an exacerbating element of volatility in financial markets during times of stress. In Spain, the financial markets’ regulator confirmed the ban for all Spanish stocks, for at least a month (Financial Times, 2020). However, the efficiency of these measures in European countries remains a subject of controversy, given that in 2018, a similar ban resulted in higher value for the restricted stocks, and an increase of probability of default and volatility on the unbanned stocks. (Alessandro,2018). Accordingly, the debate should be more focused towards the downturns of short selling positions, originating from commodities financialization, rather than commodities financializations in a whole.

On the other hand, commodities markets are confronted with stock market spillovers to the commodities’ one. They are thus held accountable for the lack of liquidity through the similarity of trading activity and volume in both asset classes at the same period. (Marshall,et Al, 2013),

The increase of investors’ presence in financial markets, has also been linked to the prices hike acceleration, especially during the 2007-2008 price bubble, where speculation has broadly contributed to the bubble creation in commodity prices (Tang and Xiong,2014). Commodities’ financialization could be responsible for the increase in correlation between oil and non-energy commodities and price of commodities becomes no longer subject only to demand and offer fluctuations. The impacts on price fluctuations are also rather linked to aggregate risk appetite for financial assets, and the investment behavior of diversified commodity index investors. (Bonato, 2019). As a result, a part of the rising concerns regarding commodities financialization arose from the lack of diversification benefits caused by the rapid growth of correlations between different asset classes and underlying’s.

Through the introduction of commodities’ financialization, the behavior of commodities has shifted from one of fundamental physical assets to that of a financial asset. The beneficial diversification previously provided by commodities as an independent asset class, remains limited due to commodities financialization. Accordingly, price fluctuations, especially in agricultural commodities, are likely to fluctuate depending on oil prices. The fluctuations eventually result in imprecision in the future commodity prices’ forecast based on traditional economic indicators. (Adams and Al.,2020).

On the other hand, the second distortion is due to the institutional investors’ investment strategies are resulting, in non-fundamental trading, called noise trading[5], causing the market to react artificially, during higher volume trading days, with financial assets experiencing significant fluctuations surging in different directions. (IMF,2011)

The IMF report of 2012 acknowledges that some argue for a connection between the financialization of commodities and price volatility. This theory proposes that increased speculative trading in commodities creates “noise” that disrupts price formation based on fundamentals like supply and demand. As a result, commodity prices become more susceptible to destabilization, and traditional factors may not fully explain price increases (IMF, 2012). However, the report focuses its analysis on more established causes. These include rising demand, particularly in developing economies where diets are shifting towards protein-rich foods, along with slowing productivity growth in agriculture and recent weather shocks that disrupted harvests. The report suggests that these trends are likely to be more influential than financial speculation in driving future food price volatility.

The distortions advanced by the report, aim to drive a link between the impact of commodities’ financialization on price formation, through the spillover of noise trading. Eventually, commodities’ prices become subject to destabilization, and fundamentals do not fully explain commodity price increases. (IMF,2012)

While focusing on the investment objectives of commodities investors, price-induced fluctuations are not similar from one category to another. In the same context, the investors’ category that has received the highest level of criticism is one of “non-commercial” speculators. The main argument is that traditional speculators buy and sell futures markets to mitigate the price risk related to the physical commodities of interest. In contrast, diversification purposes are not a priority for speculative purposes, and the returns motives came back as a top motive for investors, which eventually deepens the dependency between commodities prices and financial markets. (Mayer, et Al., 2009).

Moreover, the literature has drawn a difference between the disruption resulting in financial markets from the commodities’ financialization, leading to an association between the financialization and the amplification of soaring commodities prices, as well as the lack of fundamentality in the commodities behavior on financial markets. However, thanks to commodities financialization, several virtues appeared in the financial markets, sustaining the necessity and the utility of allowing investors to access commodities asset classes as an investment vehicle. (Plante, 2011)

Virtuous commodities’ financialization: A Multifaceted outlook embedded in the literature.

Commodities financialization offers a positive perspective through its impact on liquidity. Speculators, constantly entering and exiting positions, create a pool of potential counterparties for hedgers seeking to manage risk. Hedgers themselves contribute to short-term liquidity by entering and exiting futures contracts based on their needs. Additionally, speculation can influence price discovery by reflecting market expectations of future supply and demand.

However, the impact of speculators on prices is more nuanced. While intense hedging activity can help stabilize prices by absorbing fluctuations, it doesn’t necessarily drive them up. In fact, effective hedging can mitigate price spikes. Similarly, speculator interest doesn’t automatically translate to lower prices. Speculators can take both long (buying) and short (selling) positions. When they believe a commodity’s price will rise, they buy futures contracts, potentially pushing the price up in the short term. Conversely, if they anticipate a price decline, they might sell futures contracts (short positions), exerting downward pressure. Ultimately, the net effect of speculators on prices hinges on the overall market sentiment and their specific actions. (Kang et Al, 2014)

Before delving into the non-financial factors influencing the surge in prices of food commodities, it’s crucial to acknowledge that this phenomenon is more closely tied to shifts in consumer preferences than to the financialization of commodities. Indeed, the rising demand for luxurious tastes could significantly impact market prices, particularly evident in the consumption trends observed in emerging and developing countries experiencing economic growth. These regions are witnessing a transition in dietary habits as their populations become wealthier.

The increased consumption of high-protein foods, for instance, has led to a surge in soymeal prices for animal feed purposes. Similarly, the growing preference for edible oils reflects changing dietary patterns in numerous countries. This dietary shift implies that the consumption of grains may either decrease or grow at a slower pace. However, despite this trend, grain prices have not exhibited a corresponding decrease even a decade later.

This phenomenon can be largely attributed to the concept of price elasticity, particularly evident in dairy products, meat, and edible oils, which are considered to have a higher “income elasticity.” This means that as incomes rise, consumption of these products increases proportionally. (Helbling and Roach, 2011).

Financially speaking, a different view on the assessment between speculation and liquidity, by analyzing a broad range of 21 commodities in the energy sectors, metals, grains, and other agricultural commodities, allows understanding that long-speculation seems to meet a growing hedging need and thereby improves market liquidity. Commercial traders are increasingly using hedging to manage risk, but this can have unintended consequences. When there’s a lack of counterparties willing to take the opposite side of the hedge[6], it can drain liquidity from the market. This reduced liquidity can then make it more difficult and expensive for those same commercial traders to buy and sell the commodities they need. As a result, there might be pressure to loosen restrictions on commodity speculation, which could ironically further reduce liquidity and exacerbate the problem for commercial traders (Ludwing,2019)

In that context, the spillover impact of prices between commodities and different futures markets allows us to understand that commodities prices can also be subject to the influence of macroeconomic variants and that speculation does not stand as a relevant factor for worsening commodities’ soaring prices. (Bonato, 2016)

Traditionally, supply and demand from producers and consumers were the primary regulators of commodity prices. However, financial markets have become a significant source of demand, impacting price discovery. Recent findings show an extension of price influencers beyond traditional factors. This includes external shocks, correlations with certain currencies, such as with oil and USD[7], and even interdependencies between different commodity categories.

While the assessment of whether financial market participation has directly caused the increased influence of external factors on commodity prices remains a topic of debate, it’s crucial to explore two key areas. First, a deeper understanding of the organization and structure of commodity financial markets is needed. Second, analyzing the behavior of commodity prices during periods of high sensitivity to external political and economic factors, along with strong activity from non-commercial speculators, can provide valuable insights. By investigating these aspects, we can gain a clearer picture of how financialization interacts with traditional price determinants [8]and potentially shapes the overall price landscape for commodities.

In the European ban on short sales mentioned earlier, during 2008-2009, liquidity shortage resulted from short positions’ restrictions. In short, the bans were intended mainly to avoid a collapse of bank shares, which could result in funding problems or even a “full-fledged” bank run. However, the comparison of solvency measures, volatility, and stock returns, indicates that short-selling banks were not linked to additional stability for banks. Unorthodoxly, the bans were found to be correlated with a higher default probability, greater return volatility for banks, and the steeper stock price declines. (Beber, et Al., 2012)

While speculation might be driving the movement against commodities’ financialization, the crude oil price spike and collapse in 2007-2008 were mainly a result of an increasing world demand. (Kuffman, et Al., 2009).

Finally, among the virtues mentioned above of commodity financialization, it can benefit from introducing commodities in financial markets by reducing price asymmetries and cash market volatility, on financial markets (Shamsher ,2021).

In commodities financialization, it is not always one way or another…

The positive and negative outcomes of commodities financialization are not always narrowed down to one point of view. A more hybrid opinion can evoque the dual role of financial traders, who can consume and provide liquidity to hedgers in the financial market. The need for financial traders and hedges to mitigate and control risk can emerge, and reducing risk exposure in the futures markets becomes a necessity when the risk-bearing capacity of these agents is limited due to the spillover of events outside of the commodity market. (Cheng, et Al.,2013).

In the same context, commodity financialization positively impacts markets by providing price efficiency improvements in its early stages and later a decrease in price efficiency at the later stages of commodity financialization. While commodity producers see higher operating profits when financialization improves market efficiency, they are worse off due to reduced opportunities in futures-market trading. (Goldstein, et Al., 2022).

Are we heading towards a cycle of Renewable Energy financialization?

The trading of renewable energy remains subject to controversy, given that it represents, at the same time, beneficial aspects of renewable energy sources and could also mean a threat.

In Africa, the existence of renewable energy sources lays the ground for their introduction to financial markets in the same way conventional commodities embedded in non-renewable energy sources do. So, can we trade wind and solar power on commodities markets in the same way Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas are?

Today, the trading of renewable energy does not exist in its traditional form. Instead, it exists in Renewable Energy Certificates (RCEs). This market-based instrument represents property rights to the environmental, social, and other non-power attributes of renewable electricity generation. RECs are issued when one megawatt-hour (MWh) of electricity is generated and delivered to the electricity grid from a renewable energy resource. They can also be bought as proof for the generation of an amount of electricity from renewable sources. (EPA.gov,2023).

Besides RCEs, investment vehicles, such as stock or bond offerings, trading on financial markets, can allow funding some renewable energy projects. These instruments can be traded in financial markets, allowing investors to take part in the growth of the renewable energy sector. Introducing renewable energy sources on financial markets makes it possible to enhance investment financing in the renewable energy sector, which is crucial for developing and installing new technologies. Eventually, it is possible to harness, and more significant growth can be harnessed and generate lower costs and delays in installation, leading to increased competitiveness in renewable energy sources.

However, it is also essential to be aware of the possible downturns, such as potential market fluctuations and instability, and focus on short-term profits in long-term projects. Hence, Renewable Energy financialization can promote more extensive access to financing and growth, but remains subject to applying strict regulations, to avoid the potential inconvenience of speculation.

- Considering commodities financialization for the African Continent: Challenges and Opportunities

Even if commodities financialization started miles away from the African continent, repercussions and implications could manifest across several countries. The trade flow, as the world knows it today, relies on an absence of autarchy and a butterfly effect fueled by globalization. The accentuation of poverty in an African country due to the war in Ukraine and the impact of the Niña in South America on the wheat supply in North Africa[9] are only two among several examples in which commodities markets are under the impact of factors starting in a different country.

Organized commodity trading in Africa is embedded within the history of commodity financialization in the continent.

Although that organized financial markets, when it comes to commodities, are only located in a few places, their impact is more globalized than their localized scope. As an example, the most significant commodities exchanges are in the United States of America (Chicago Mercantile Exchange Group and the Chicago Board of Trade), Japan (Tokyo Commodity Exchange), France, Belgium, Netherlands, Portugal, and the United Kingdom (Euronext), in China (Dalian Commodity Exchange), in India (Multi Commodity Exchange), as well as in the USA, Canada, China and the United Kingdom (Intercontinental Exchange). However, since the emergence of the benefits of introducing commodities to financial markets, the relevance of having organized commodities financial trading places has grown more tangible.

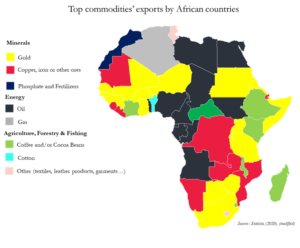

The urge to organize commodities markets in Africa has originated in trade. However, the extent of the importance of commodities’ export in the continent stands for the accuracy of commodities’ role in African economies. Although that focus has been attributed to agricultural commodities (Mbeng M, et Al, 2013), the exchange includes high export levels, including minerals and fuels, as they are an essential part of the continent’s exports, as well as fertilizers and oil products. The aim was thus for the African continent to have broad financial market exchange platforms, allowing for the introduction or the financialization of a set of commodities’ asset classes in the continent.

The relevance of commodities’ financialization in the African continent

Among the arguments for the relevancy of commodities’ financialization in the African continent, stands the diversity in exported commodities, as highlighted in figure (1) of this paper, as well as their critical role in today’s geopolitical dynamics. Besides the diversity, which constitutes a vital asset for the continent, circumstantial events can make a country keener to integrating commodity financialization to benefit from solid momentum linked to their core commodities.

As mentioned above in this paper, and as per the arguments of virtuous commodities financialization, it’s possible to witness the benefits of commodity financialization in Africa through providing access to new sources of capital, the increase of transparency and liquidity in commodity financial markets. Moreover, hedging against price risk exposure stand out as an essential benefit, and allows producers to hedge against price swings through financial tools such as futures and contracts, especially in periods of price volatility and market shocks, induced by fundamental elements, such as the war in Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic.

In addition, financialization can be a source of further investment in the continent. However, it’s crucial to note that financialization is not a “one solution fits all” measure, that can be applied without deep reconfiguration to benefit both investors and producers, according to the commodity type and market nature[10].

Figure1: Most exported commodities by African countries in 2020

Today and tomorrow, commodities’ financialization presents a double-edged sword for African countries. On one hand, it offers a chance for significant rewards for nations with abundant resources. This includes both non-renewable energy sources, which are crucial for meeting current global energy demands, and renewable energy sources. The push towards Net Zero emissions and the Paris Agreement will significantly increase the demand for the metals needed in renewable energy technologies, creating a strong market for African countries with these resources.

However, commodities’ financialization can also have drawbacks for African nations. It can lead to a narrow focus on exporting raw materials, hindering the development of domestic industries that add value to these resources. In the same context, due to the sanctions applied on Russia, the European Energy supply shortage resulted in a shift in supply destinations in terms of energy sources. African countries became an essential source for fulfilling European energy needs, given their oil and gas resources. Nigeria became an attractive source of oil supply while Mozambique and Senegal stood out as crucial sources of Gas, and Morocco for Hydrogen. African countries expect growth in demand for non-renewable and renewable energy sources (Foundethakis,2022).

For energy commodities, for instance, the demand for global oil demand could peak by 2027, while for the global gas demand, it could peak by 2040. However, if leading countries achieve net-zero commitments, the global oil demand could peak as soon as 2024, and gas demand around 2030 (Leke, et Al, 2022). Although that acceleration of energy transition could impact the oil and gas exports of African countries, there is still room for harvesting the benefits of commodities’ financialization on short-medium terms. In that sense, Nigeria, have abundant natural resources, including zinc (OPEC,2023), which is used for green power and solar panels, and iron ore, which is used in wind turbines (IMF,2021).

The importance of having developed African commodity trading markets allows for harnessing several benefits for the continent, from an economic development point of view, risk mitigation for actors, and adding regulation to financial markets in the continent.

Between harnessing liquidity and leveraging transparency in the African financial markets

Several factors can be traced back to the inefficiency of African Financial Markets. Evidence from the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) and the Nigerian Stock Exchange sustains that African markets are identified as the least liquid stock markets in the world, even though their existence is highly important, and their growth potential is immense. In that sense, both Stock Exchanges, when considering the number of transactions, it is still insufficient and remains subject to improvement that can be provided to the increase of trading frequency instead of the trading value (Kenfack, et Al, 2018). The lack of liquidity in African Financial Exchange places can also be traced back to (1) Limited Investor Participation, (2) Inadequate regulation, (3) lack of strong economic fundamentals, as well as (4) Limited Product Offerings and Infrastructural Constraints.

Case studies of African commodities places: Evidence from the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange (ECX), the Johannesburg Stock Exchange and the Ethiopian Stock Exchange

The Ethiopian experience

As part of Ethiopia’s agricultural action plan in 2003, one of the key action points was to explore the feasibility of establishing a commodity exchange. Previous research conducted by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), had revealed that much of Ethiopia’s cereals trade resembled a primitive open outcry exchange system. Additionally, there were discussions about transforming the existing coffee auction into a commodity exchange system, a transformation that later materialized into an electronic auction system in 2005.

In 2005, the Ethiopian Development Research Institute published a report recommending an integrated initiative for commodity exchange development, encompassing all aspects of the system, including the establishment of a warehouse receipts system. This recommendation catalyzed the process, leading to the creation of the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange (ECX) in 2006, with substantial support from various development partners such as UNDP, World Bank, USAID, Canadian Development Agency, and World Food Programme. ECX commenced its trading operations in April 2008.

Initially, ECX operated with an open outcry spot trading mechanism, requiring deliveries to be based on warehouse receipts. While ECX had the legal authority to certify third-party warehouse operators, it opted to manage all delivery warehouses itself, issuing electronic warehouse receipts upon receiving goods. This practice allowed these receipts to be traded on the exchange or used as collateral for bank loans. ECX quickly expanded its warehousing network, starting with a single coffee warehouse in April 2008 and eventually reaching 57 warehouses by early 2013, with plans to establish a separate company for warehousing operations.

ECX’s trading journey evolved from initially trading grains like maize and wheat with limited success to becoming a significant player in the coffee market, largely supported by the Ethiopian government’s decision to replace traditional coffee auctions with ECX. This decision led to a substantial increase in trading volumes. In September 2011, ECX obtained monopoly trading rights for two other export commodities, sesame and pea beans, with discussions about potentially mandating wheat and maize trading through ECX in 2013. Moreover, ECX explored the possibility of adding new commodities, including hides and leather, to its trading portfolio, solidifying its position as Africa’s largest exchange, following South Africa’s SAFEX.

The South African experience

South Africa is home to one exchange, SAFEX, which is the largest in Africa, trading well over a hundred thousand contracts a month since 2002. SAFEX was created in 1988 as a currency trading platform, and in 1995 (in anticipation of the expected deregulation of agricultural trade, including the abolition of fixed-price purchases and marketing boards), introduced agricultural futures contracts. Currently, SAFEX offers contracts for white and yellow maize, bread milling wheat, sunflower seeds, and soybeans. SAFEX prices are an important reference for grain trade in several neighboring countries.

The commodity trade on SAFEX was organized through a new Agricultural Markets Division, which rapidly attracted a total of 84 members who collectively provided the commodity exchange’s start-up capital of US$ 1 million. The exchange was set up as a non-for-profit mutual exchange. Its trading and clearing platforms were those used for SAFEX’s financial products. In 2001, SAFEX was acquired by the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (a for-profit, publicly listed company), but retained its brand name; however, the commodity trading division was renamed to Agricultural Products Division.

SAFEX initially started with beef and potatoes futures contracts, both cash-settled, but both were unsuccessful and delisted two years later. SAFEX’s first successful contract was launched only in May 1996, a futures contract on the country’s main staple crop, white maize (it was launched alongside a yellow maize contract). The provisions of the 1996 Agricultural Marketing Act were set to come into effect on January 1, 1997, and the grain industry needed new mechanisms. SAFEX met the challenge by setting up its contracts around a robust delivery system, using transferable silo receipts, thus simultaneously creating a proper environment for both spot and futures trade.

White maize still accounts for the largest share of trading on the exchange, representing about 40% of the trading value. When the Wheat Board was deregulated in 1997, wheat futures were added. Option contracts for maize and wheat were introduced in 1998. The trading volume for maize is now 15-20 times the production volume, and for wheat, 8-10 times; these numbers are fairly normal in an international context.

Futures and options for sunflower seeds were added in 1999. In 2000, a second white maize contract was introduced to deal with maize qualities that were below those specified in the original contract (this second contract was discontinued in late 2002 but then reintroduced in mid-2006).

It is worth noting that when agricultural futures trading started in South Africa, there were no applicable laws and regulations. The exchange essentially operated as a self-regulatory organization, with users having signed up to the exchange’s rules. SAFEX’s maize contracts are settled through physical delivery. This made it necessary to involve the major silo operators. Over time, most of the significant silo operators have indeed registered with the exchange – there are now 19 registered silo operators with a total of almost 200 registered delivery points. Warehouse operators issue electronic warehouse receipts, which act as the delivery instrument into the exchange.

The agricultural futures market in South Africa remains relatively narrow – in 2009, SAFEX reported a total of 12,000 clients for its agricultural platform. As of 2009, it was estimated that hedgers accounted for 60% of open positions, with the largest users being commercial farmers and processors. Speculators and arbitrageurs accounted for the remainder; this is a very low percentage compared to global commodity futures markets. The market has five clearing members, and despite some problems with physical deliveries, there has not been a default. Clearing members guarantee all transactions and positions of their respective trading members and clients.

The exchange is used by most large-scale producers, in part because the banks that finance them require the producers to hedge their price risk. SAFEX widely disseminates its market data, and the SAFEX price is widely used as the reference price in forward contracts, including for regional grain trade. In 2005, this allowed the government of Malawi to use SAFEX options to protect itself against the risk of future price increases of its maize imports (after this, Malawi became a maize exporter and used options to protect its export prices; also, using related financial instruments, it replicated a maize buffer stock).

In 2009, a licensing agreement was signed with the world’s largest exchange group, the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME). The agreement with CME permitted SAFEX to introduce contracts denominated in the local currency that were indexed to CME contracts (maize, gold, crude oil), allowing proxy access to the international market for South African investors (strict currency controls make direct access impossible for many). The range of commodities traded under the agreement has expanded over the years; in April 2013, heating oil, gasoline, natural gas, palladium, sugar, cotton, cocoa, and coffee were added. A similar licensing agreement was signed in 2012 with the Kansas City Board of Trade, and later that year, with the Zambia Agricultural Commodity Exchange.

SAFEX is overseen by the Financial Services Board, established in 1990, which also regulates the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. It operates under the Securities Services Act of 2004, which brought control over the various financial markets and instruments under one umbrella. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s self-regulatory authority is recognized under the Act. Another Act regulates intermediaries, requiring them, for example, to pass a fit and proper person test before they can be licensed. Implementation of the Act is overseen by the Financial Services Board.

Impact of commodities financialization, and speculation on the African financial markets

The study of the speculative and hedging activities in the South African white maize futures market using proxies derived from trading data, the results indicate a significant presence of speculation over hedging during the period analyzed. In this particular market, volatility is primarily influenced by changes in fundamentals rather than excess speculation, and restrictive regulations could hinder market efficiency and liquidity needed by stakeholders such as farmers.

It is also possible to link the thinness and the illiquidity of African Stock Markets to the market capitalization, which only represents 48.29% of the GDP percentage in the continent. In comparison, South Africa was ranked first in the continent in 2020, with a 311.45% rate, and Morocco was second with a 54.04% rate. In comparison, other energy commodities exporting countries have higher rates. Saudi Arabia, a significant oil producer, had a 345.35% rate, and Kuwait had a 100.03%. The highest rate was, however, 1777.28% and registered in Hong Kong, due to factors such as (1) Economic Stability, (2) low levels of inflation, (3) high-quality infrastructure, (4) a developed financial market as well as a (5) strategic location. (The Global Economy, 2020). In Saudi Arabia, the growth is mainly related to the sharp rise in oil prices and production power recovery since the COVID-19-induced recession in 2020, as well as contained inflation, despite higher prices for imported commodities. (Mati and Rehman,2022)

When considering the mismatching between regulation and potential for prosperous financialization in African markets, the policies and regulations related to financial technologies are still absent from most African countries, resulting in a limited ability for jurisdictions to tackle the inherent risks, and reduce the potential of financial technology and alternative finance (UNCTAD,2022). The lack of liquidity, weak investor base, low market capitalization, poor regulatory framework and poor accounting, and reporting standards stand among the challenges of African financial markets, among different asset classes ranging from equities to bonds and commodities (Afego, et Al,2015).

Challenges of Commodities financialization on the African continent

If tackled from the wrong perspective, commodities financialization, especially in the African continent, can lead into negative impacts on the economy. In fact, financialization leads to a ‘four low economy’ in that scenario, characterized by low investment, low employment, low wages, and low productivity, exacerbating distributional conflicts and shaping the domestic political economy.

The international financial system, facilitated by technological changes, has led to various effects on global accumulation and economic and social reproduction, including entrenched secrecy and both legal and illicit financial flows detrimental to developing economies. These flows have become part of corporate strategy for tax and wage avoidance, as well as facilitating corruption, including instances of ‘State Capture.’ In South Africa, such practices have enriched certain individuals and corporate interests, leading to systematic campaigns against state institutions. However, despite evidence of negative impacts, there is a continued push for financial deepening by international financial institutions and national governments, which will generate new financialization trajectories. It cautions other African societies against further financial liberalization or promotion as financial centers, based on the South African experience.

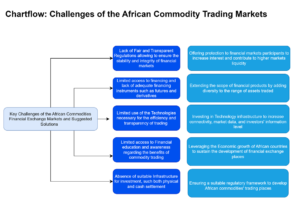

To that extent, the chart flow in Figure (2) of this paper highlights some of the major challenges that African commodity trading markets are facing and potential areas of improvement. The efficiency of African commodities’ financialization remains strongly linked to criteria such as liquidity, fluidity, and information, enhancing actors to contribute to the upgrade of commodities’ financial markets in the region.

As mentioned in the first part of this paper, evidence from the literature sustains the role of commodity financialization in bringing liquidity to financial markets and contributes to improving regulation and transparency, implementing proper fair and transparent regulation, stability, and integrity, which eventually leads to a rise in the investors’ interest in African commodity markets. Moreover, commodity trading markets in Africa could benefit from more robust infrastructure, such as storage and transportation, enhancing the well-functioning commodities markets, especially for physical settlements. In addition, raising awareness regarding commodity trading benefits can contribute to the rise of attraction in terms of benefits and opportunities for investors in commodities markets while bridging the gap between small-scale producers and investors and eventually leading to higher liquidity.

Figure2: Challenges and potential Improvements for African Commodity Trading markets

The case studies examined in this paper, shed light on the complexities and impacts of commodities financialization in Africa. The establishment of ECX in Ethiopia exemplifies a deliberate effort to modernize and formalize commodity trading, primarily in the agricultural sector. Through its innovative approaches such as electronic trading and warehouse receipt systems, ECX has significantly transformed Ethiopia’s commodity markets, particularly in coffee trading.

On the other hand, SAFEX in South Africa represents a more established and mature commodity exchange, with a broader range of contracts and significant trading volumes. Despite its success, SAFEX has also faced challenges, including regulatory gaps and the need for continuous adaptation to changing market dynamics.

The study of speculative and hedging activities in these markets underscores the importance of addressing regulatory frameworks and ensuring market efficiency and liquidity. While financialization can bring benefits such as liquidity and transparency, it also poses risks, including exacerbating inequality and facilitating illicit financial flows.

To navigate these challenges, African commodity markets need to focus on enhancing regulatory frameworks, improving infrastructure, and raising awareness among market participants. By promoting fair and transparent regulations, enhancing infrastructure, and fostering investor education, African commodity markets can realize their potential as engines of economic growth and development. Ultimately, a well-functioning commodities market can contribute to broader economic stability and prosperity across the continent.

Conclusion and policy recommendations:

The trend towards embracing commodities financialization in Africa could be expected to strengthen in the coming years due to the numerous benefits it offers, including liquidity enhancement, improved market efficiency, hedging opportunities, diversification of investment opportunities, and more accurate pricing mechanisms. However, alongside these benefits come inherent challenges, such as the risk of market inefficiency stemming from non-commercial speculators’ activities, increased volatility, and a greater dependency on financial markets.

In Africa, these challenges can be even more complex given the continent’s unique context. Examples from countries like Ethiopia and South Africa illustrate the intricacies involved in modernizing and formalizing commodity trading, whether in agriculture, metals, or energy commodities. Any efforts in this direction must be approached with caution, taking into account the continent’s specific challenges. Leveraging technology and establishing robust regulatory frameworks could offer potential solutions that not only benefit the commodities market but also contribute to overall economic growth.

Determining the suitable timing for African countries to integrate commodities financialization into their agendas is a nuanced issue. The appropriateness of timing varies depending on each country’s specific context, including the strength and transparency of its financial markets and its economic resilience. Experiences from different countries around the world have shown varied outcomes in organized commodities financial markets. It’s essential that the transition to commodities financialization prioritizes the country’s development and well-being over investor interests, with any positive impacts on investors being treated as externalities of establishing an organized commodity market. Timing should be carefully considered to ensure that the transition aligns with the country’s developmental needs and goals.

Bibliographic references:

- Alessandro, 2018, https://www.esrb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/wp/esrb.wp64.en.pdf

- Achille, C, et.Al, 2013. “AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP Guidebook on African Commodity and Derivatives Exchanges.” https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/Guidebook_on_African_Commodity_and_Derivatives_Exchanges.pdf.

- Adelegan, Olatundun Janet. 2009. “The Derivatives Market in South Africa: Lessons for Sub-Saharan African Countries.” IMF Working Papers 2009 (196). https://doi.org/10.5089/9781451873436.001.A001

- Adam et,Al, 2020 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0140988320301092

- Afego, et.Al, 2015, https://www.epa.gov/green-power-markets/renewable-energy-certificates-recs#:~:text=RECs%20and%20Offsets%3F-,What%20is%20a%20REC%3F,attributes%20of%20renewable%20electricity%20generatio

- Alemu, Dawit , and Gerdien Meijerink. 2010. “The Ethiopian Commodity Exchange (ECX) an Overview. Dawit Alemu & Gerdien Meijerink June PDF Free Download.” Docplayer.net. 2010. https://docplayer.net/19449373-The-ethiopian-commodity-exchange-ecx-an-overview-dawit-alemu-gerdien-meijerink-june-2010.html

- Aparissi, 2021, https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/2021-04/12609iied.pdf

- Beber, et.Al, 2012, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2012.01802.x

- Bonato, 2016, https://ideas.repec.org/p/rza/wpaper/587.html

- Bonato, 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S104244311830009X

- I, and Xiong,W., , 2013, The financialization of commodity markets, https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2350243

- Brahmbhatt, M.; Canuto, O. and Vostroknutova, E. (2020). Dealing with Dutch Disease, World Bank, Economic Premise n. 16, June.

- A., and Anseeuw, W., 2013, http://www.iippe.org/wp_new2/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/Antoine-Ducastel-Agriculture-as-an-asset-class.-Financialisation-of-the-South-African-farming-sector.pdf

- Foundethakis, 2022, Africa: Higher prices for commodities – Good news for the continent, but challenges remain, https://www.globalcompliancenews.com/2022/06/01/africa-higher-prices-for-commodities-good-news-for-the-continent-but-challenges-remain-12052022/

- Goldstein, I., and Yang,L, 2022, Commodity financialization and information transmission, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jofi.13165

- Hernandez, et. Al, 2017, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/26155893.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Abd03cb7180dc50e95618d4d36851bb3b&ab_segments=&origin=&initiator=&acceptTC=1

- Hernandez, Manuel A., Shahidur Rashid, Solomon Lemma, and Tadesse Kuma. 2015. “Market Institutions and Price Relationships: The Case of Coffee in the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 99 (3): 683–704. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aaw101.

- Helbing and Roach, 2011, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2011/03/helbling.htm

- IFPRI, 2008, https://www.ifpri.org/sites/default/files/News%20Release/pressrel20080414.pdf

- IMF,2021, https://www.imf.org/en/Blogs/Articles/2021/12/08/metals-demand-from-energy-transition-may-top-current-global-supply#:~:text=For%20green%20power%2C%20solar%20panels,ore%2C%20copper%2C%20and%20aluminum

- IMF, 2012, Chapter4, commodity price swings and commodity exporters

- Kang et,Al, 2014, The role of hedgers and speculators in liquidity provision to commodity futures”, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227437260_Did_speculation_drive_oil_prices_Market_fundamentals_suggest_otherwise

- Kenfack, P., et. Al, 2018, The determinants of Illiquidity on emerging stock markets: a comparative analysis between the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) and the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE),

- R, and Ullman, B., 2009, Oil prices speculation and fundamentals: Interpreting causal relations among spot and futures prices https://www.researchgate.net/publication/223498119_Oil_prices_speculation_and_fundamentals_Interpreting_causal_relations_among_spot_and_futures_prices

- Leke, et.Al, 2022, “The future of African oil and gas: Positioning for the energy transition”, https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/oil-and-gas/our-insights/the-future-of-african-oil-and-gas-positioning-for-the-energy-transition

- Ludwing, 2019, “Speculation and its impact on liquidity in commodity markets”, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301420717305603#

- Marshall, et.Al, 2013, “Liquidity commonality in commodities” https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S037842661200235X#

- Mati and Rehman, 2022, “Saudi Arabia to Grow at Fastest Pace in a Decade”, https://www.imf.org/en/News/Articles/2022/08/09/CF-Saudi-Arabia-to-grow-at-fastest-pace

- Mbeng, et., Al, 2013, « Guidebook on African commodity and derivatives exchanges” https://www.afdb.org/fileadmin/uploads/afdb/Documents/Publications/Guidebook_on_African_Commodity_and_Derivatives_Exchanges.pdf

- OPEC,2023, https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/167.htm

- Plante, 2011, « Did speculation drive oil markets fundamentals suggest otherwise”, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227437260_Did_speculation_drive_oil_prices_Market_fundamentals_suggest_otherwise

- Rashid, Shahidur, and Alex Winter-Nelson Garcia. 2010. “Purpose and Potential for Commodity Exchanges in African Economies.” https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/5231/filename/5232.pdf

- Tang and Xiong, 2014, Index Investment and Financialization of Commodities, https://wxiong.mycpanel.princeton.edu/papers/Xiong%20NBER%20Reporter%202014.pdf

- UNCTAD, 2009, https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ditccom20089_en.pdf

ZAUDE GABRE-MADHIN, ELENI , and IAN GOGGIN GOGGIN. 2005. “Does Ethiopia Need a Commodity Exchange? An Integrated Approach to Market Development.” Ifpri.org. 2005. https://www.ifpri.org/publication/does-ethiopia-need-commodity-exchange

[1] According to Brahmbatt, Canuto and Vostroknutova (2010), The Dutch disease refers to changes in a country’s production structure following a positive shock, like the discovery of a significant natural resource or a rise in the international price of an exportable commodity. This phenomenon is expected to lead to structural changes, including a contraction or stagnation in other tradable sectors of the economy and an appreciation of the country’s real exchange rate. When the booming sector involves oil or minerals, the declining tradable sectors typically include manufacturing and agriculture. While these changes are expected to be beneficial due to increased national income, they can raise concerns if the declining sectors possess unique characteristics that could drive long-term growth and welfare, such as increasing returns to scale or positive technological externalities. Dutch disease concerns may also arise from large and sustained inflows of private capital or foreign aid. The condition can have implications for productivity dynamics and volatility, prompting policymakers to consider various responses involving fiscal, exchange rate, and structural reform policies.

[2] Market integrity in this context refers to the maintenance of fair, transparent and orderly financial market.

[3] An Over-The-Counter derivative refers to the financial contract concluded between two consenting parties, that does not imply nor trading or exchange of an asset but is however adapted to the needs of each party. In contrast to open markets, the OTC market, implies that a transaction’s terms and conditions are only agreed upon, within counter parties.

[4] This can lead to increased market volatility as their actions can create sudden price movements. For example, if a group of noncommercial traders collectively take positions, this can create sudden price changes that they can then profit from.”

[5] Noise trading corresponds to the act of trading regardless of fundamental or technical analysis, but rather based on incomplete, inaccurate, or irrational trading. Accordingly, noise trading causes market divergences. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported around 50 million non-professional traders in the market as of 2022, VS 2.8 professional investors. A number that is growing due to the emergence of self-directed trading platforms. (Corporate Finance Institute, 2022).

[6] Long buy positions have to be met with short sell positions otherwise it creates a market movement shifted towards the buy side or the sell side and limits the liquidity available on the market

[7] Oil and USD have typically been moving in opposite directions. In the context of stronger dollar, it weighs on the oil prices, by making it expensive of other currencies holders, and thus negatively impacting crude demand. In 2019, the oil and dollar have been moving in the same direction, with the positive correlation peak, attained in May 2019. The usual inverse correlation between oil and USD has been mostly witnessed in 2020, and 2021, when cured demand was subject to global pandemic repercussions.

8. The weather phenomenon known as the Niña creates severe drought and dry conditions in several parts of the world, endangering the crops of producing and exporting countries such as Brazil, Argentina and the United States, as well as causing additional rain in other areas, such as Australia. Even if a country such as Algeria buys milling wheat originating in France, the damage to crop levels in some of the key producing countries causes a drop in the crop quality of exporting countries, higher market prices and more severe competition.

[9] The weather phenomenon known as the Niña contributes creates severe drought and dry conditions in several parts of the world, putting into prejudice the crop of producing and exporting countries such as Brazil, Argentina, and the United States, as well as bringing additional rains in other areas such as Australia. With damage in crop levels in some of the key producing countries, even if a country such as Algeria rather buys Milling Wheat originated from France, the drop in the crop quality of exporting countries contributes to higher prices on the markets, as well as more severe competition given the rationality of supporting the supply of importing countries around the globe.

[10] For example, in 2008, the Ethiopian Commodity Exchange Market (ECX), mainly known for coffee trading, faced opprobrium from the international coffee community. The financialization of coffee in Ethiopia, induced a loss in the link between producers and buyers, and made it impossible for buyers on the market, to identify and buy coffee. By 2009, the EXC managed to adapt its trading system to allow buyers from international markets to find an answer to their demands, while maintaining the existing benefits for local producers through competitive sales. (Mbeng, et Al, 2013)