Brazil president’s surge in polls worries investors

Joe Leahy in São Paulo OCTOBER 1, 2014

Brazil’s former president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has been defiant in his backing of his protégé, Dilma Rousseff, as she soars in the polls ahead of the country’s presidential election beginning on Sunday.

While markets plunged on the news of the resurgent fortunes of the incumbent president, who investors regard as interventionist, Mr Lula da Silva said no one had asked for their vote.

“Well I won in 2002 and I never asked for the market’s vote . . . Dilma won in 2010 and she didn’t ask for their vote and she will win in 2014,” he said in São Paulo.

In fact, Mr Lula da Silva did ask for the market’s vote in 2002 when, as a former firebrand trade unionist, he published an “open letter to the Brazilian people” assuring them he would respect contracts and control fiscal spending should he win office.

But he was right about Ms Rousseff, who has never tipped her hat to the capitalists. Indeed, if anything, she has moved so far to the left in her campaign this year that some are worried she will be unable to return towards the centre if she wins the election, which is likely to go to a second round run-off on October 26.

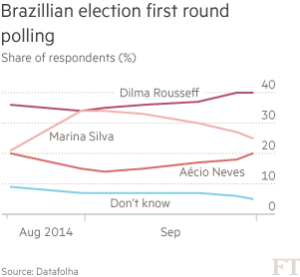

A second-term Rousseff government that is considered even more interfering than allegedly the present one is the markets’ worst nightmare. Polls on Tuesday evening showed the president was widening her lead by as much as 9 percentage points over her main rival, Marina Silva, a former senator with a more investor-friendly platform.

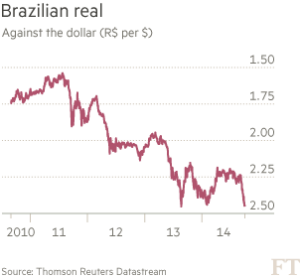

Brazil’s currency, the real, has weakened 9.5 per cent in the third quarter, the most in three years, while the Ibovespa share index plunged 11.7 per cent in September.

“She [Dilma] has been burning bridges with markets over the past few weeks,” said one economist with a UK-based bank. Like many, he did not want to identify himself for fear of retribution from the government, which recently took Santander Bank to task for publishing analysis unfavourable to Ms Rousseff. “She’s taking a step to the left on everything she talks about.”

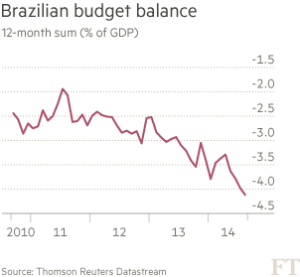

Not only has Ms Rousseff flatly denied there are any problems with government policy, in spite of the economy slipping into technical recession in the first half of the year, she has also criticised the notion of an independent central bank and rejected the need for serious tightening of the budget deficit or winding in of state lending, both of which have increased sharply under her rule.

She has extended a minimum wage rise formula based on last year’s inflation plus gross domestic product from the year, a move economists criticise as embedding inflationary pressure into the economy and increasing wages without regard to future productivity or sustainability.

“The only thing she cares about now is being re-elected,” said another economist from a bank in São Paulo, who did not want to be named.

Economists are split, however, on whether Ms Rousseff’s election rhetoric means she will not make market-friendly adjustments if she wins re-election.

She has already indicated she will replace Guido Mantega, her finance minister, in a gesture interpreted as intended to placate markets. Mooted replacements have included Otaviano Canuto, former secretary for international affairs in the finance ministry and a World Bank official, and Nelson Barbosa, a former finance secretary.

But analysts caution that her leftist rhetoric and reputation for micromanagement could deter top level talent from joining her next government.

On the fiscal front, she may be forced to make adjustments, economists say. The public sector’s budget deficit rose to more than 4.62 per cent of GDP between January and August, the highest for the period in at least 13 years, Reuters reported.

Gross public debt has risen to 60.1 per cent of GDP from 56.7 per cent in 2013, while net public debt is 35.9 per cent, up from 33.6 per cent in December. While the government argues net public debt is low, economists prefer to use the gross figure, which is more transparent.

“Now they [the opposition] are talking about a profound fiscal adjustment, which is not necessary,” Ms Rousseff said on the campaign trail last week.

However, Standard & Poor’s has already downgraded Brazil to one notch above junk, and Moody’s Investors Service has warned it will do the same if economic growth and fiscal management do not improve.

“The reality will probably force them to promote some small adjustments,” said Alberto Ramos, economist with Goldman Sachs in New York.

Still, Brazil remains a largely closed economy. The central bank has plenty of dry powder in the form of one of the world’s largest foreign exchange reserves to protect the currency, which could buy the next government some time.

Mr Lula da Silva may therefore be technically right – Ms Rousseff does not need the markets to win the election. But life might be easier with them onside once she begins the hard work of getting the economy back on to a growth track in 2015.