(forthcoming at) Policy Center for the New South and Capital Finance International

China’s economic growth has been in a downslide trend since 2011, while its economic structure has gradually rebalanced toward lower dependence on investments and current-account surpluses. Steadiness in that trajectory has been accompanied by rising levels of domestic private debt, as well as slow progress in rebalancing private and public sector roles. As the ongoing trade war with the US continues to unfold, it remains unclear at which growth pace China’s rebalancing will tend to settle.

The need to rebalance China’s economic growth

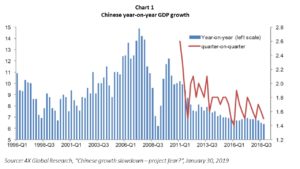

China’s GDP growth last year (6.6%) was the lowest in the last two decades. In its World Economic Prospects update in January, the IMF maintained China’s annual growth rates forecast for 2019-2020 at 6.2%. Such rates correspond to a continuation of the downslide in growth (Chart 1).

China’s growth slowdown had been expected, as signs of relative exhaustion of the pattern of extraordinary growth-cum-poverty-reduction – which prevailed over the previous three decades – became clear by the start of the decade. Back in 2011, while serving as vice-president at the World Bank, I represented the institution at the 10-Year Anniversary of China’s Access to the World Trade Organization (WTO), at the Hall of People in Beijing. In my remarks to then President Hu Jintao, I conveyed some of the thinking that was later fully endorsed in a 2013 joint report by the World Bank and the Development Research Center of the State Council, P.R.C. (“China 2030 – building a modern, harmonious, and creative society”):

“According to studies done by the World Bank and other international institutions, China has the potential to continue its dynamic growth, quadruple per capita income to about $16,000, and become the world’s largest economy by 2030. But, to realize that potential, China needs to overcome emerging new challenges, adapt its growth model to avoid the middle-income trap, reduce its large trade surpluses to mitigate tensions with trading partners, and increasingly play an active leadership role in global forums and multilateral institutions:

First, China will need to increase services and consumption. By 2030, the World Bank estimates that China’s service sector could expand from 43 percent of GDP today to almost 60 percent. Consumption could also expand to 60 percent, from about 50 percent today.

Second, given China’s rising real wages, China will need to upgrade to higher value-added industries, and progressively shift its labor-intensive production to lower-cost locations in Asia and Africa. This shift implies an increase in outward FDI.

Third, China needs to reform its state-owned enterprises to boost private sector growth and competition.

Finally, to ensure sustainable growth, China will need to shift to a greener growth model.”

In his final remarks at the event, President Hu Jintao stated:

“China will unswervingly commit to the opening-up strategy to help itself grow and promote global development.”

It had become clear that the Chinese pattern of rapid growth with structural change had been accompanied by rising economic imbalances, while the main pillars of growth seemed to be gradually weakening (Canuto, 2013). High and sustained GDP growth rates were based on very elevated investment to GDP ratios, which in turn were only possible with low shares of wage income and domestic consumption, as well as cheap and repressed finance. Another contributing factor was dynamic markets abroad willing and capable of absorbing a huge Chinese export expansion, something that could not be expected to continue indefinitely, particularly given the size of China’s economy. Growing income disparities were also a domestic flipside of that model, becoming potential sources of social strain, in addition to changes in the external environment. As former Premier Wen Jiabao had said in 2007, the country’s economic growth trajectory was “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable”.

Three mutually reinforcing paths of transformation were clearly ahead, with a structural slowdown of growth looking predictably to be in the cards. First, the productivity increases achieved through transferring resources from low-productivity agriculture activities to industry — a typical feature of economies moving from low- to middle-income levels (Canuto, 2011) (Agenor et al, 2012) — had to a large extent already taken place. On the demographic front, the old-age dependency ratio had already started to rise. Furthermore, gains in economic efficiency and technological progress thus far, based on the absorption of existing imported technologies, would from then on need to be increasingly replaced by local innovative efforts. Meanwhile, the set of second-generation policy reforms this entailed would take time to bear fruit, whereas low-hanging fruits in terms of productivity increases would be less available.

Second, a much-needed sector-structure rebalance was also expected. Higher shares of services and consumption, following rising wages, coupled with a decrease in exports, savings and investment ratios to GDP, would need to accompany the increased reliance on domestic sources of aggregate demand. Government consumption was also to rise, in order to meet social demands, as well as the needs of operations and maintenance. The income gap between coastal areas and middle and western regions were projected to fall as the pool of underemployed labor shrank. Interestingly, the perception of increased prosperity by the population would likely be higher than before, with the expansion of purchasing power, despite the somewhat lower GDP growth rates due to lower investment-to-GDP ratios and more limited total factor productivity increases.

Third, a shift up the value chain in both tradable and non-tradable activities would underpin the previous paths of change. A transition to more sophisticated production processes was by then a target already being pursued.

In a nutshell, while moving to a less spectacular growth trajectory than before, China would be morphing into a mass-consumer market economy combined with a supply capacity increasingly reliant on “total factor productivity” growth.

Debt leverage and high profile of SOEs along China’s gradual growth rebalance with downslide

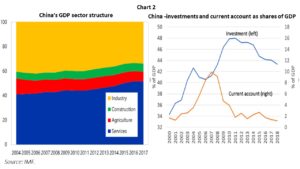

Clarity regarding the roadmap ahead, however, did not mean ease of crossing it straightforwardly. While the GDP sector structure has been evolving as expected, reliance on both investment and current-account surpluses has since diminished (Chart 2).

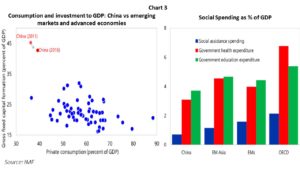

On the other hand, the transition toward a less investment-and-export-dependent growth model evolved from a starting point of very low consumption ratios to GDP (Chart 3, left side). In addition to high ratios of profit to wages, low levels of public social spending have led to high household savings (Chart 3, right side). It is no wonder that rebalancing toward a consumption-based growth model would have only gradually been pursued, as otherwise GDP growth rates might have collapsed, rather than less abruptly slide down from two digits. After all, the change in growth pattern would require time-intensive structural reforms. In 2017, private consumption and investment were, respectively, 39% and 44% of GDP – yet an outlier as compared to the rest of the world, where 60% is the average consumption to GDP ratio (Chart 3, left side).

Furthermore, like elsewhere, fears of a quasi-collapse of the global economy in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis were followed by countercyclical policies. In the case of China, a “Great Quantitative Easing (QE)” took the form of a combination of “shadow banking” and capital expenditures on housing and infrastructure, with a high role played by special purpose vehicles (SPVs) associated with subnational entities (Canuto and Zhuang, 2015). In this context, lending by non-bank entities through shadow finance accounted for about two-fifths of new credit by 2016.

Over the last decade, two features of China’s economic policies have, on one hand, been instrumental to sustaining the smoothness of the growth downslide to this point in time, but over time also become sources of concern:

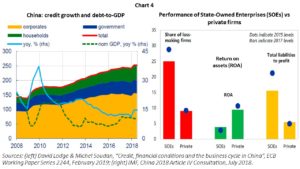

First, the attainment of official target growth rates in tandem with the gradual slide depicted in Chart 1 has been accompanied by overcapacity in certain heavy-industry and construction sectors as well as by increasing debt leverage of corporates and households. Such debt trajectory vulnerability was mitigated by Chinese authorities through periodic loosening of fiscal, monetary and financial restrictions, so as to avoid drastic declines in growth rates or critical points. This is depicted in the evolution of corporate and household debt as well as in the comparison of credit and nominal GDP growth rates presented in Chart 4, left side.

Second, the “reform of state-owned enterprises to boost private sector growth and competition” – mentioned in my remarks in 2011, and at the time referred to by Chinese authorities as part of a “rebalance between public and private sectors” – has stalled. Credit continues to be preferentially channeled to state businesses and competition between private firms and SOEs remains uneven in sectors where the latter was expected to gain space. While large state-owned banks continue lending to SOEs, infrastructure and real estate investments are supported by shadow finance. In parallel, performance indicators suggest that the failure to reform state-owned businesses has resulted in costs on productivity and foregoing real returns (Chart 4, right side).

Opposing directions in terms of motivations for tackling financial risk and avoiding a sharp growth slowdown have been pursued with an attempted “policy fine-tuning” via selected, targeted measures of tax cuts, de-risking and regulatory changes. Meanwhile, China’s public capital stock per head has already reached levels well above those of economies with comparable per capita income, levels of residential and infrastructure investments increased dramatically, and the export-led slice of growth faces rising challenges. This in turn poses a difficulty due to decreasing returns in terms of additional output obtained with the maintenance of high investments and debt accumulation.

Over the past decade, China has thwarted the many potential “incoming financial disruptions”, and still retains abundant fiscal space and enough foreign reserves to implement any necessary official bail-outs. On the other hand, avoiding a deeper growth downslide by maintaining policies in place tends to become harder to achieve, as returns from investment-cum-debt at the margin are decreasing. With the increasing amount of capital investment needed to yield incremental output units, China’s ability to hold steady the recent shares of investment in its GDP would require the accumulation of ever-increasing levels of debt.

The US-China trade war

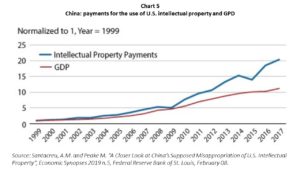

The ongoing trade disputes between U.S. and China, predominantly sparked by the former, were largely undertaken with a double motivation: to force changes in bilateral trade flows in its favor as well as in Chinese policies and practices regarding technology transfer (Canuto, 2018a). China’s rebalance toward raising its presence in higher value-added stages in global value chains have included piggybacking at low costs on external technological sources. To this end, forced technology transfers have been imposed on foreign investors interested in serving domestic markets, in addition to non-recognition of intellectual property, subsidies to state-owned companies, non-tariff barriers and the like. That has happened even as China’s payments for the use of U.S. intellectual property have increased faster than the former’s GDP (Chart 5).

On the trade side of the confrontation, the negative impact on China’s exports in 2018 has added challenges to maintaining growth, albeit secondary to those so far discussed. On technology transfer policies, Chinese authorities may be prepared to offer something meaningful. Given the fact that their ambitions regarding technological breakthrough are now increasingly hinging on local, tacit and idiosyncratic knowledge – (Canuto, 2018b) -– the Chinese cost-benefit calculation toward finding alternative forms of local technology support may well lean them in favor of reaching an agreement. This, in turn, would allow them to focus on the domestic challenges of rebalancing, without the additional burden of trade confrontation, as a rational choice of the rulers of that country.

Bottomline

China’s economic growth has been in a downslide trend since 2011, while its economic structure has gradually rebalanced toward lower dependence on investments and current-account surpluses. Steadiness in that trajectory has been accompanied by rising levels of domestic private debt, as well as slow progress in rebalancing private and public sector roles. As the ongoing trade war with the US continues to unfold, it remains unclear at which growth pace China’s rebalancing will tend to settle. Given the weight China has achieved in the global economy – on trade, investment and financial flows – the world should have its fingers crossed in favor of its success in rebalancing without abruptly sliding growth down.

Otaviano Canuto is principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development, a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South and a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank.

This Post Has 3 Comments

Oba COLEGA!!!

Preciosa análise explicativos graficos.

Parabéns e obrigado

Obrigado

OC

Pingback: Como é a metamorfose nos fluxos de capital da China para a América Latina – Center for Macroeconomics and Development

Comments are closed.