Policy Center for the New South

Seeking Alpha; TheStreet.com

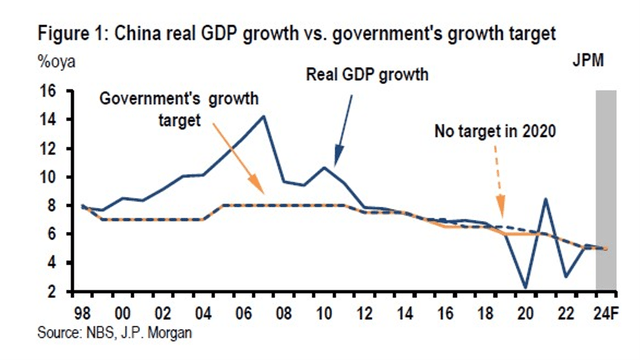

The IMF World Economic Outlook released on Tuesday (April 16th) brought a projection of China’s economic growth of 4.6% and 4.1% for, respectively, this year and next. In 2023, after the economic reopening with the end of the “Covid zero” policy, the rate was 5.2%, above the official target of 5% (Figure 1).

This year, the official target has been set up at 5% again. Notwithstanding the challenges approached here, the macroeconomic performance in the first quarter of 2024 has been in sync with such target (He et al, 2024).

JPMorgan

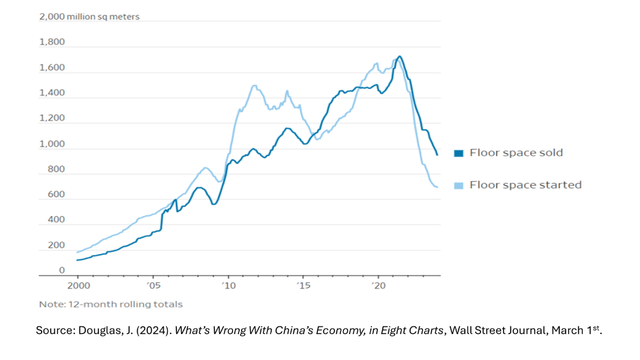

Six challenges can be identified for China’s economic growth in the coming years. First, the exhaustion of the real estate sector as a growth factor, after having reached up to a quarter of the country’s GDP. The restrictions established in 2021 by the Chinese government on developers’ access to cheap credit, due to concerns about the proportions reached by the real estate bubble, not only cut the boom, but also exposed the fragility of developers’ assets, as seen straight away in the case of Evergrande. Since then, there has been a sharp drop in home sales, new construction, and investment in the sector (figure 2).

Figure 2 – China: Residential Construction and Sales

Wall Street Journal

In addition to the level of debt of fragile real estate companies, the debt of local governments is another problem. Especially because theirs revenues from the sale of land to real estate developers have shrunk. The degree of exposure of Chinese banks to both, with possible consequences in terms of loan losses, could negatively affect the supply of credit in the economy.

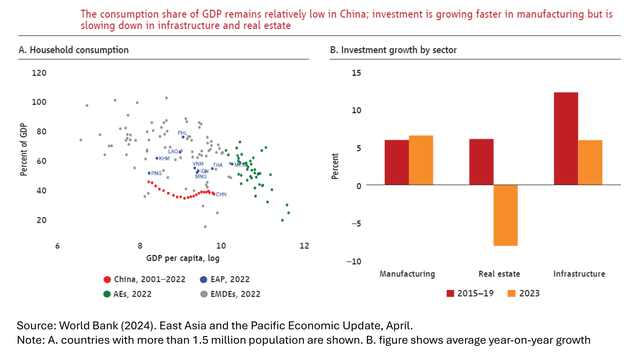

A problem with domestic demand by families represents a third challenge for growth. Chinese families took on heavy debt to buy real estate during the boom, and spending cuts accompanied the housing turbulence. Even though it increased after the end of “Covid zero” last year, consumption remains on a trajectory below that before the pandemic (figure 3, left side). Measures of consumer confidence point to this.

Private investments for the domestic market, as well as hiring, accompanied this retraction of domestic consumers. While investment in manufacturing kept pace, it slowed down in real estate and infrastructure (Figure 3, right side).

Figure 3 – China: Low Consumption and Investments

World Bank

What about the external sector as a form of compensation? A fourth challenge to growth lies in external resistance to such an increase in exports as an alternative, given that they now face the intensification of geopolitical rivalry abroad, especially in the USA and other advanced economies. Not by chance, so much talk has been given to a “second shock” in terms of Chinese exports on the rest of the world, particularly because of the size of China’s figures this time.

The Chinese lead in clean energy technology has, in fact, been accompanied by a strong expansion, for example, in sales of electric cars abroad. Chinese passenger car exports have surpassed Japan’s, while Chinese companies are seeking to strengthen positions abroad – such as BYD in Brazil, Hungary and elsewhere. But the risks of facing additional market access restrictions are high.

A fifth challenge concerns the radical change in the mood of foreign investors. Since the third quarter of last year, China’s balance of payments has recorded a net outflow of almost 12 billion dollars in direct investment, due to asset sales or non-reinvestment of profits. Portfolio investments, that is, shares and debt securities, also changed signs.

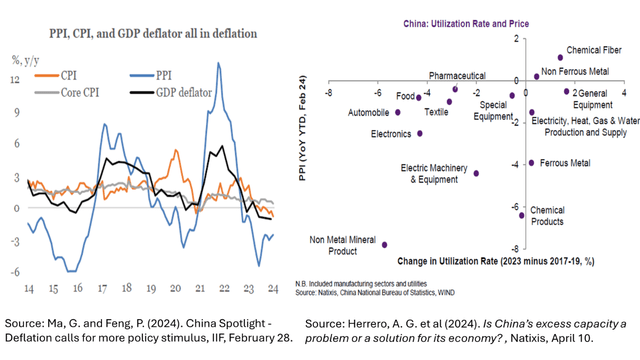

The insufficiency of aggregate demand in China has been manifesting itself in the form of deflation in the domestic economy. Consumer prices have been stable or falling for months and companies have been reducing prices for more than a year (Figure 4 – left side). Idle capacity is high in many sectors, reflecting the excess investments relative to levels of demand (Figure 4 – right side).

Figure 4 – China: Deflation and Capacity Utilization Rates

IIF; Natixis

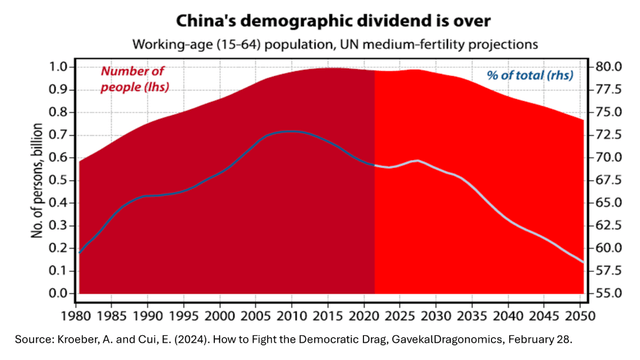

Demography constitutes a sixth challenge. The increase in the supply of workers accompanying rapid urbanization has reached its limits. The long-term decline in the number of babies and the ongoing population decline, with a growing share of the population out of the job market, means – as in many other parts of the world – the end of the demographic dividend (Andrade and Canuto, 2024) (Figure 5).The currently high youth unemployment rate provides a source of work to be employed, but this does not change the direction on the issue of the proportion of Chinese people of non-productive age.

Figure 5 – China’s Demographics

Gavekal

To understand how the first four challenges above intertwine, it is worth going back to the beginning of the last decade. In December 2011, when the writer was one of the vice-presidents of the World Bank, I was at a ceremony in Beijing in which then-president Hu Jintao made one of the first statements about the need for an inevitable “rebalancing” of the Chinese economy. There would have to be a gradual redirection towards a new growth pattern, no longer associated with investment rates close to 50% of GDP and with domestic consumption increasing in relation to investments and exports.

Also, said Hu Jintao, an effort would be needed to consolidate local insertion in the highest rungs of the added value ladder in global value chains, something that was effectively sought. Services should also increase their weight in GDP in relation to manufacturing. There would no longer be the double-digit GDP growth rates of previous decades, but growth would no longer be, as then-premier Wen Jiabao said in 2007, “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable”.

Given the low level of domestic consumption in GDP (a fact that is still present) and, therefore, the dependence on investments and trade balances, the transition would run the risk of experiencing an abrupt drop in the pace of growth. To allay fears of an abrupt slowdown, waves of credit-driven overinvestment in infrastructure and housing followed in later years. A second round was implemented in 2015–2017 in response to a housing slowdown and stock market decline. In addition, of course, to the expansion policies adopted during the pandemic crisis in 2020.

In effect, the decline in Chinese GDP growth rates occurred only gradually to 6% in 2019. Now, however, the lever of overinvestment in real estate and infrastructure is running out. Not only because of the debt levels that accompanied its extensive use, but also because, at the margin, its returns in terms of GDP growth presented a declining contribution.

Two reforms would have a strong effect on growth (Canuto, 2022). First, reinforce social protection in order to convince Chinese people to save less. Furthermore, resume the proposal made by Hu Jintao in 2011 – left aside by Xi Jinping – to “rebalance” public and private companies, with a consequent gain in productivity due to the differences favorable to the latter shown where they operate together.

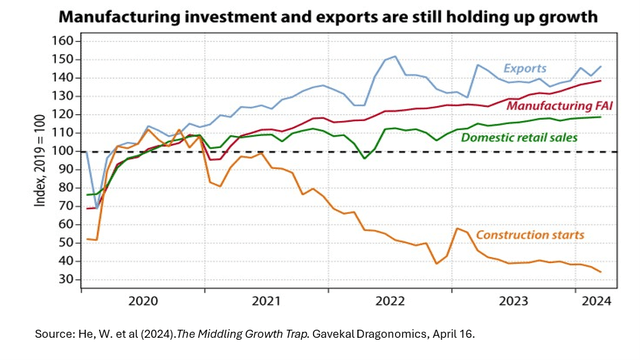

Such reforms do not seem to be on the frontline ahead. However, despite the challenges approached here, China’s economic growth path remained steady in the first quarter of the year. Exports, manufacturing investment and travel-related consumer spending compensated for the drag from the property sector (Figure 5), so far lifting the chances of achieving the target of “around 5%” GDP growth this year (He et al, 2024).

Figure 6 – China: growth despite the property sector drag

Gavekal

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a former vice president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil. Currently, he is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, distinguished visiting scholar to the International Institute of Science and Technology Policy – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development.