Otaviano Canuto and Tayeb Ghazi

Rapport annuel sur l’économie de l’Afrique 2022, Policy Center for the New South

Partie III : Inter-régionalité et intégration continentale – Ch. 5 (p. 299-314)

Introduction

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are digital versions of cash issued and regulated by central banks. They correspond to digital money denominated in the national unit of account and liability of the central bank.

By mid-2022, almost 100 CBDCs were being subject to research or testing. Two had already been launched, one of them in Nigeria (eNaira) and the other in the Bahamas. According to a survey by the BIS (Bank for International Settlements) last year, 90% of central banks there approached were undertaking CBDC analysis or projects in the previous year, with 26% already implementing pilot projects (Kosse and Mattei, 2022).

Potential benefits from CBDCs include t the facilitation of financial inclusion, more resilient domestic payments, and enhanced competition. Beyond improving access to money, payment efficiency and lower transaction costs may be attained. On the other hand, some risks and challenges will have to be faced.

As we approach in this chapter, African central banks are part of such a global trend. Most are yet in the beginning (research and analysis), while Nigeria has already issued a retail CBDC, and South Africa and Ghana are implementing pilot projects (wholesale and retail, respectively).

First, we summarize how a monetary system can be strengthened with digital finance and new private forms of digital money, if not being based on cryptocurrencies. CBDCs can enhance the public good nature of the monetary system, with the central bank at the core of safe, low-cost, and inclusive payments. Some broad risks and challenges are also highlighted.

Second, we approach the motivations of African central banks, in particular, with respect to CBDCs. Finally, we call attention to some of the challenges and risks accompanying such a move to CBDCs.

-

Features of monetary systems: today, the crypto universe, and future

A. From money to digital money

Money functions comprise being a store of value, a unit of account, and a means of exchange or payment. Money is widely believed to have been created to enable the exchange of goods and services without the need for synchronization (in time and space) imposed by the barter economy.

Trust by its users while it performs those functions is of the essence for the well-functioning money and payment systems. The monetary system (money and payment systems) is the set of institutions and arrangements that supports monetary exchange.

The history of money is long and complex. Its origins go back to antiquity: an economic and social innovation in which users’ trust is the central pillar. Over history, “commodity money” has given place to “fiat money”. After historical and geographically specific experiences with unregulated “free banking”, national systems evolved toward one featuring central banks and regulations at their core.

In early times, it was precious metals (gold, silver, and others) that made possible the exchange of goods and services, but above all for the expansion of trade between far locations (e.g., bimetallic systems, referring to gold/silver weight, used in the Muslim world in the 10th century). Over time, the institution evolved, and the first coins allowed people to pay according to the number of coins rather than their weight.

Then came the invention of banks and the banking system, whose modern origins date back to the Middle Ages and the Renaissance in Italy. This invention gave rise to new and more complex forms of money, such as banknotes issued by banks or governments, but also to new economic and financial phenomena and disputes. One of the oldest revolved around the need – or not – for an intrinsic value of the money issued, opposing the followers of the currency school and the gold standard (the quantity in circulation must have an equivalent in gold or silver reserves) to those of the banking school proclaiming a certain autonomy of the banking system (the quantity in circulation must refer only to economic circumstances).

Nowadays, fintech is revolutionizing the financial sector by improving the quality and availability of products/services, as well as payment and transfer methods. It has the potential to enhance productivity in various industries and reduce transaction costs through disintermediation, increased transparency, and verifiability.

Its instruments, including bitcoin and other crypto-assets, are often touted as alternative means of payment to central bank-issued currencies. This is especially interesting because StableCoins offer similar benefits to crypto-assets while aiming to address their volatility by linking their value to “real” assets. StableCoins could also improve cross-border payments, which, are slow, expensive, and opaque. However, other risks associated with StableCoins persist. These include money laundering and terrorist financing, cyber-attack resilience, and consumer and investor protection.

From this perspective, it is worth recalling the arguments often put forward by central banks and public authorities against fintech instruments: crypto-assets have no legal status and are not regulated, they are unanchored assets with a risk of substantial volatility, and their limited acceptance make it challenging to use them as a store of value or reliable means of payment.

Nevertheless, central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) are attracting a great deal of interest from central banks and major international financial institutions, and many have begun studies and experiments to explore the possibility of offering a digital currency that could replace traditional money.

The People’s Bank of China was the first central bank to introduce a digital version of its currency, the yuan, as part of its efforts to digitalize the economy. Unlike crypto-currencies and crypto-assets the central digital currency is more secure and less volatile. It is a digital version of coins and banknotes issued and regulated by a central bank. Relying on trust in central banks and their networks, the development of central digital currencies offers a safe and viable alternative to private digital currencies, which could reassert the monetary sovereignty threatened by the decentralization of the crypto universe.

Public authorities recognize the benefits of digitalizing the financial sector, such as job creation, convenience, personalization of products and services, and reduction of costs and delays. However, regulatory and competition challenges arise due to the combination of the characteristics of the digital business model and their global reach. Concerns include increased concentration, dominant positions, AI algorithms, cyber security risks, and data protection. Decision-makers must then take these considerations into account to control risks while retaining the benefits of digitalization. They must constantly adapt legal frameworks to ensure a healthy development of the rapidly changing digital environment.

B. The basis of the future monetary system

Money and payments evolved, and digital is now a major component of payment systems. Every day, 2 billion payments are made using digital technology; and this concerns a multitude of financial transactions (buying/selling, lending/borrowing, foreign exchange, etc.).

Of course, it is thanks to innovation that we have reached this stage. However, the system players (central and commercial banks as well as other private payment service providers) have played the leading role in promoting the use of digital, thanks to their competition, their positions, and the trust they place in digital systems.

In recent years, large-scale innovations in the crypto world took an increasing hold in the world of money and finance. Based on the principle of decentralization (decentralized finance or “DeFi”), crypto seeks to replicate traditional financial services, replacing central banks and trusted intermediaries with innovations such as programmability and composability on permissionless blockchains.

DeFi seems to have a certain adaptability to future developments and user needs. This is possible thanks to the features of programmability, composability and tokenization that open the way to new functions. DeFi is inherently borderless and allows for global transactions 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

However, cryptocurrencies are not money, as they do not perform money functions with their necessary attributes. They lack security and stability. Stable currencies have to import their credibility through a nominal peg to the dollar or another currency. Crypto-currencies do not fulfill the basic functions of money ( i.e., store of value, a unit of measurement, and medium of exchange). Also, transactions in the DeFi world lack supervision and control, which leaves room for illicit practices and prevents adequate protection of personal data. In terms of efficiency, this world is prone to fragmentation. The evolution of its applications often leads to congestion and high fees, resulting in costly transactions and new incentives for speculation. It is unlikely that these structural shortcomings of the crypto-currency universe can be remedied by technical solutions alone. This is because they reflect the inherent limitations of a decentralized system built on permissionless blockchains.

A future system should then overcome these structural deficiencies while allowing private sector innovation to flourish and benefit the general public. If based on public goods and the confidence provided by the presence of central banks, this system should ensure safer prompt payments (stable sovereign currencies and secure payment systems), greater transparency and accountability (clear mandates and regulation), greater efficiency (speed of payments and lower costs), increased access and use by individuals of transaction accounts and payment instruments (which is not the case with DeFi and the conventional system), protection and control over personal data, prevention of illicit practices, adaptation to future developments and needs, and promotion of payments both within and across borders.

CBDCs seem to offer a future vision combining the benefits of new digital technologies but with a central role for central banks. They would provide confidence and support the smooth functioning of the payment system by providing sufficient liquidity for settlement and preserving the integrity of the payment system through regulation, oversight control.

Table 1 (first column) displays the high-level goals to be attained by a monetary system. The table compares the attributes of the monetary system as it exists today, the crypto universe, and the future system where CBDCs have a key role to play (BIS, 2022). Today’s monetary system makes safety and stability possible but fails to perform optimally on the other goals. The crypto universe, in turn, offers adaptability and openness, while failing or being subpar in the others. The future system, incorporating CBDCs and digital technology, may provide positive results on all goals.

However, one must not lose sight that CBDCs come with risks and challenges that central banks must face. One most obvious is that users might withdraw too much money from banks all at once to purchase CBDCs, which could trigger a crisis. Central banks will also need to strengthen their capacity to manage risks posed by cyberattacks, while also ensuring data privacy and financial integrity.

Table 1 – High-level goals of the monetary system

| High-level goals |

Today’s monetary system |

Crypto universe (to date) | Future monetary system (vision) |

| 1. Safety and stability –money needs to perform fundamental functions: as a store of value, unit of account, and medium of exchange | Sovereign currencies can offer price stability, and public oversight has helped achieve safe and robust payment systems | Cryptocurrencies do not perform money’s fundamental functions, and stablecoins need to import their credibility | Innovations grounded in trust in the central bank feature stable sovereign currencies and safe payment systems |

| 2. Accountability – public mandates and regulation should ensure that key nodes in the system are accountable and transparent to users and society | Supervision, regulation, and oversight tackle risks, promote competition and protect consumers, but public mandates may need to adapt to change | Crypto and DeFi create a parallel financial system to circumvent the regulation, with no accountability to the public | Clear mandates and regulation balance risks and benefits to harness innovation and stimulate efficiency |

| 3. Efficiency – the system should provide low-cost, fast payments and throughput | Domestic payments are often expensive, and financial institutions collect rents | High congestion and rents lead to costly transactions and new speculative incentives | New payment systems can significantly reduce payment costs and rents, supporting economic activity |

| 4. Inclusion – the system should ensure universal access to basic services at affordable prices | Many people lack access to transaction accounts and digital payment instruments | Crypto and DeFi have not yet served to enhance financial inclusion | New service providers and interfaces can address barriers to inclusion and better serve the unbanked |

| 5. User control over data – data governance arrangements should ensure users’ privacy and control over data | Users trust intermediaries to keep data safe, but they do not have sufficient control over their data | Transactions are public on the blockchain – which will not work with “real names.” | New data architectures can give users privacy and control over their data |

| 6. Integrity – the system should avoid illicit activity such as money laundering, financing of terrorism, and fraud | Payment systems are subject to extensive regulation, but illicit activity persists in cash and account fraud | Pseudo-anonymity is prone to abuse by illicit actors, and the DeFi sector is rife with fraud and theft; identification is needed | New technologies can help to better prevent illicit activity and improve on today’s systems |

| 7. Adaptability – the system should anticipate future developments and users’ needs and foster competition and innovation | Payment systems are adapting to demands but are not yet at the technological frontier | Programmability, composability, and tokenisation give scope for new functions | Programmability, composability, and tokenisation can be offered in a CBDC or through tokenised deposits |

| 8. Openness – the system should allow for seamless cross-border use | Despite progress, cross-border payments are still slow, opaque, and expensive | DeFi is by nature borderless and allows global transactions, but without adequate oversight | Multi-CBDC arrangements and other reforms mean cheaper, faster, and safer cross-border transactions |

Source: BIS Annual Economic Report 2022

Note: Green denotes that a policy goal is broadly fulfilled, yellow that there is room for improvement, and red that it is not generally fulfilled.

-

Central bank digital currencies in Africa: the motivations

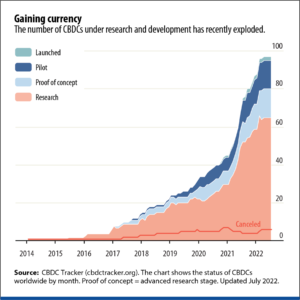

With China leading the race for digital currency projects, so far, many countries around the world are planning to launch central bank digital currencies. In 2021, 90% of central banks surveyed by the BIS were engaged in analysis or development projects for central bank digital currencies. This compares to two-thirds in 2017 (Alberola and Mattei, 2022). Figure 1 (from Stanley, 2022) displays how research into CBDCs increased globally, sparked by technological advances and a decline in the use of cash.

Figure 1

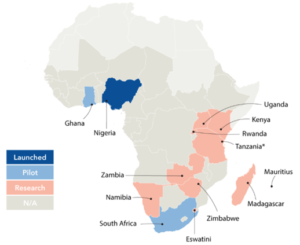

This global trend is not lost on African central banks. Indeed, Nigeria launched the e-Naira in October 2021, and several sub-Saharan African central banks are considering the possibility of creating a digital currency, as is the case in Rwanda and Kenya, or have set up experimental projects, as is the case in South Africa and Ghana (Figure 2). In North Africa, two central banks are currently studying the possibilities of a digital currency: Morocco and Tunisia.

Figure 2 – African CBDCs

Source: Fuje, H.; Quayyum, S.; and Ouattara, F. (2022).

The enthusiasm of African central banks for digital currencies is now driven by the solutions they offer to overcome several CBDCs would help address many of Africa’s current and future challenges. They open up important avenues for financial inclusion on the continent, and many African countries are looking to use them to overcome the infrastructure problems affecting their banking sectors, but more importantly to provide financial services to the hundreds of millions of Africans who do not have a bank account.

For all African central banks surveyed, promoting financial inclusion is one of the top three reasons for issuing a digital currency and the main reason for more than a third of them. Indeed, CBDCs can mitigate some of the market imperfections that prevent financial inclusion in Africa. These include, as mentioned above, providing an open infrastructure to payment service providers and consumers, promoting competition, and reducing the costs of payment services. This would benefit Africans if the barriers of access and inadequate ICT infrastructure are removed, except for the informal sector – which is over-represented in employment and production, and prefers the anonymity of cash.

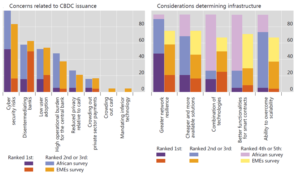

According to the BIS survey with African central banks, the provision of cash in digital form and the promotion of financial inclusion feature on the top of motivations for CBDC issuance (Figure 3, left side). Compared with other Emerging Market Economies (EMEs) also surveyed by the BIS (2022b), financial inclusion surpasses digital cash as a top motivation. Higher relevance is attributed to diminishing cash distribution costs and monetary policy improvements. Enhancing competition and the programmability of money are considered as less necessary in relative terms.

Figure 3 – Benefits of CBDCs and barriers to financial inclusion (% of participating central banks)

Note: Each bar indicates the percentage of central banks that choose a given motivation as one of their top three benefits of CBDC/barrier to financial inclusion. Unless otherwise stated, the percentage is computed over all the central banks that participated in the surveys (19 and 24 central banks in the African and EME survey, respectively), including those that did not answer the specific question.

Source: Alberola and Mattei (2022).

In addition to financial inclusion, CBDCs can reduce the high cost of cross-border and domestic payments, facilitate them, and increase trade. This is good news for trade in the continent, as everyone can trade abroad.

Also, CBDCs would contribute to improving the effectiveness of monetary and financial policy by facilitating and accelerating their implementation. Indeed, CBDCs can help reduce the costs of having less cash in circulation, improve the transmission of monetary policies, promote transparency, optimize taxation, support the distribution of targeted social benefits, etc.

Encouraging competition and money’s programmability are less motivations for African central banks. Nevertheless, more than half of the African central banks surveyed put them at the top of the considerations. CBDCs can positively impact the competitive landscape of the payment system and costs, as it creates a level playing field through its open nature. They could also support the digitalization and formalization of economic activity.

-

Major central banks’ concerns regarding CBDC issuance in Africa.

In contrast to the enthusiasm for CBDCs that has been generated by the motivations above, there are several concerns, most of them operational. Its implementation in Africa would still require time and resources and the development of new legal, regulatory and management frameworks. Indeed, the issuance of CBDCs places a heavy burden on central banks to maintain the system, its resilience and stability. It also raises concerns about cybersecurity, the potential for user adoption, and the risks of banking disintermediation (especially in a direct system where the central bank handles private financial service providers and user activities)[1].

Investigating the main CBDC-related concerns in Africa puts cyber security at the top (Figure 4). It is among the top three concerns of all African central banks and tops the list for more than half. Given the multiple links to the financial and digital ecosystem in a CBDC world, this risk is very important regarding its impact on the entire system, including user assets, financial ecosystem data, bank reputation, etc.

Other critical operational challenges are system maintenance, including network resilience, availability, and combinability of technologies, adaptability, and functionality. Indeed, CBDC systems must be secure, stable, robust, and capable of recovering from operational failures without affecting the system’s reputation.

The issue of disintermediation is also a serious concern, especially in a direct architecture where the central bank handles private financial service providers and user activities. For more than half of the African central banks surveyed, banking disintermediation is the first or second concern in the issuance of CBDCs.

Africa is particularly concerned when it comes to CBDC adoption. This is the second biggest concern for African central banks, particularly in North Africa, where digital payment penetration is relatively limited. Structural barriers to CBDC adoption in Africa also include lack of access points and inadequate ICT infrastructure as well as financial or digital illiteracy. In addition to penetration, commercial banks and private financial service providers may be reluctant to adopt CBDCs, especially in a direct architecture, favoring disintermediation. This is also the case for the informal sector, which prefers the anonymity of cash.

Figure 4 – Main concerns related to CBDCs (% of participating central banks)

Note: Each bar on « concerns related to CBDC issuance » indicates the percentage of central banks that choose a given downside as one of their top three concerns, whereas each bar on the right side indicates the percentage of central banks that choose a given motivation as one of their top five considerations regarding infrastructure.

Source: Alberola and Mattei (2022).

Concerning system infrastructure, African central banks report that its design should consider the need for greater network resilience, cheaper and more available solutions, provision of a mix of technologies, better functionality for smart contracts, and the ability to meet scalability needs.

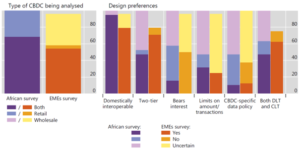

In addition to the system infrastructure, there is the question of the type of CBDC. In principle, there are two types of CBDC: retail or general CBDC, such as cash, which is universally available to the public and can be promoted anonymously, and wholesale CBDC, which is available only to certain financial institutions. As shown in Figure 5, African central banks are looking at retail and wholesale CBDCs, with a third focusing only on retail.

In addition to the choice of CBDC type, African central banks show a strong prefer preferability features (1.e. the ease with which funds can flow between the CBDC and other national payment systems).

The degree of involvement of central banks is also essential for central banks in Africa at a time when more than 90% prefer to design two-tier systems, with the central bank at the core. Still, private financial service providers interacting with users (less disintermediation). Central banks in Africa are also relatively less supportive of remuneration, as they want to provide a digital payment like cash and make monetary policy more efficient. They are less certain when it comes to the issues of imposing limits on payments via CBDCs and specific data governance policies (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Types of CBDCs and design preferences (% of participating central banks)

Source: Alberola and Mattei (2022).

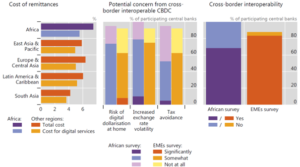

In addition to domestic issues, the issuance of CBDCs is motivated by the strong preference of African central banks for the features of international interoperability and reduced transfer costs (Figure 6). CBDCs would allow better monitoring of capital flows, and benefit commercial payments and trade financing, especially intra-African trade. All African central banks surveyed expect a reduction in costs and delays, particularly for remittances, due to greater streamlining of intermediation.

However, many risks are associated with the use of cross-border CBDCs. These include currency substitution risks (dollarization of local economies), exchange rate volatility, and tax evasion. More than half of the African central banks surveyed have concerns about these risks.

Figure 6 – Cross-border CDBCs

Source: Alberola and Mattei (2022).

4. The digital financial transformation and CBDC in Morocco

Public authorities in Morocco have considered financial inclusion a critical concern for several years. Although Morocco has a deep financial system by international standards, there are significant inequalities in access. Only 34% of adults in Morocco have a bank account, with substantial gaps by gender, age, and geographic location.

Against this backdrop, Morocco has begun a new era in financial inclusion. Mobile payment has been adopted as a first step to take advantage of the high penetration of cell phones in Morocco. Thus, a secure, interoperable, and low-cost national mobile payment solution has been implemented with the participation of banks, telecom operators, and licensed payment institutions. However, merchant take-up remains low, and the tax incentives introduced by the Ministry of Finance (Finance Law 2020), combined with communication and awareness-raising efforts, should help develop the system.

Mobile payments are not the only lever for financial inclusion; microfinance and microinsurance are also being worked on to become channels for inclusion. Efforts have also been made to strengthen financial education, drawing on international best practices. Also, the rapid development of banking services to fintech can bring benefits in terms of financial inclusion, including cost reduction and faster transaction execution. The priorities for public authorities are to target the most disadvantaged groups to reduce the gaps and to leverage the growth of fintech. As such, Bank Al-Maghrib has set up two new structures for financial inclusion and digital transformation with a five-year roadmap.

The digital revolution brings opportunities, risks, and challenges, notably in terms of cybercrime, money laundering, and terrorist financing, and personal data protection. As a central bank, Bank Al-Maghrib emphasizes a more agile and adapted regulation for the banking sector, with specific support and supervision for new players, and suggests that successful financial inclusion requires significant financial and human resources.

Encouraging innovation and use of digital tech for market growth is a global competitiveness factor. Regulators must accompany these innovations in a responsible manner to protect society and respect citizens’ rights. It is important to adopt proportionate, simple, clear, and trustworthy regulatory approaches for businesses and consumers, requiring close collaboration between regulators at national and global levels.

Thanks to the digital revolution in the financial sector, established banks will modernize their service by adopting financial technology. New companies will offer specialized financial services without challenging the incumbent players. The competition will be enhanced and beneficial to the consumer. This aspect is taken into account by Bank Al-Maghrib as part of its regulatory role and is reflected through the application of the same rules to all players, without differentiation between the status of shareholders (public or private, Moroccan or foreign) and the opening of the banking sector to new players, in particular, participatory banks and payment institutions and the upcoming launch of the activity of collaborative financing or “crowdfunding”, which has the advantage of strengthening the product offering and financial inclusion. A 2013 study by the Competition Council showed effective competition in the Moroccan banking sector thanks to increasing banking coverage, transparency of information, bank innovation and financial inclusion policy.

Morocco is closely monitoring these developments and considering the national implications regarding opportunities and risks. It is counting on the contribution of fintech as part of its financial inclusion strategy to ensure equitable access to formal financial products and services. As an indication, the national strategy is based on two axes: the development of alternative models to reach excluded populations and the creation of conditions for an increased use of financial products. The country also insists on considering the new risks linked to technological developments and the need to strike a balance between developing innovative financial services and preserving the resilience and protection of consumers and businesses. In this sense, Morocco is striving to strike a balance between financial inclusion and risk control through its 2019-2023 strategic plan by identifying financial risks and anticipating the potential effects of financial innovations.

It has set up a “One Stop Shop Fintech” to assist fintechs with aspects related to banking regulations and an “Innovation Lab” to test solutions proposed by fintechs concerning its activities. Bank Al-Maghrib has also carried out, in collaboration with its partners, several projects aimed at strengthening the development levers of the fintech ecosystem and, more broadly, at the digitalization of financial services. These include the contribution to the implementation of the online authentication and identification system for banking services users via the national trusted third-party system, whose framework agreement was signed in February of 2023 with the DGSN[2], the CNDP[3], and the GPBM[4], the supervision of the use of the Cloud and the development of digital trust services. In addition, a new market dynamic is expected with the upcoming introduction of Open Banking, a powerful lever for innovation, research, and development in the banking field.

Bank Al-Maghrib manages cyber risks thanks to two directives on penetration testing and the public cloud and reinforced cooperation with the DGSSI[5]. Internally, Bank Al-Maghrib has adopted a comprehensive security approach integrating people, processes, and technology through a cyber-security governance framework based on an international benchmark and a CERTIV to prevent, detect and react to cyber risks. In addition, Bank Al-Maghrib’s Data strategy, launched in 2021, is based on a comprehensive data management and governance framework that promotes transparency, facilitates access to data for its ecosystem, and drives competitiveness with efficient exploitation.

Bank Al-Maghrib and the Competition Council have committed to strengthening their collaboration via a cooperation agreement in 2020, which sets the scope of collaboration and information exchange, and provides a framework for consultation and exchange of expertise on areas of common interest (law n°20-13). Bank Al-Maghrib has also multiplied cooperation agreements with regulatory authorities and national institutions (CNDP, ANRT[6], ANRF[7], AMMC[8], INPPLC[9], DGSN, Office des Changes, Administration de la Douane) and with several central banks abroad.

Also, Bank Al-Maghrib created, on February 18, 2021, an institutional committee in charge of studying the risks and benefits of a Central Bank Digital Currency and crypto-assets for the national economy. The central bank remains cautious in its approach by choosing a gradual evolution of the legal framework with the participation of international institutions. It believes that a clear regulation must be developed before considering the launch of a virtual currency and that the monitoring of active developments must be done so as not to be outdated and so that there is no divide between Morocco and the developed countries.

-

Concluding remarks

As in the rest of the world, African central banks have increased their attention on the potential benefits of issuing and operating with CBDCs. The region has not moved as fast as elsewhere, with some exceptions (like Nigeria). In relative terms, there are fewer projects at advanced stages, either pilot or live. Fast-payment systems in East and West Africa through mobile money have performed well, but half of the central banks consider CBDCs a potentially better solution.

The ways central banks approach CBDCs reflect differences in motivations, concerns, and other country-specific features. Financial inclusion ranks on top of the motivations for CBDCs. Like elsewhere, African central banks want to reach higher payment system efficiency. However, given the weaknesses of monetary policy transmission in the region, the high power propitiated by CDBCs in that regard is also being considered, even more so than in the case of other EMEs.

While CBDCs have grabbed African central banks’ attention and disposition to examine their adoption, cyber security risks and cross-border spillovers rank even higher than in advanced economies as concerns. High operational burdens are also feared. Furthermore, high degrees of informality hindering adoption are also an item among concerns.

As approached in the BIS survey, the choice of CBDC designs will embed trade-offs involved. For instance, choices regarding limits and remuneration of CBDCs will depend on the priority attributed to avoiding bank disintermediation and strengthening adoption, as they impact the onboarding of the banking sector. Digital infrastructure, levels of penetration and width of fast-payment systems, levels of financial literacy and of competition in the payment system, among others, will shape the goals searched with CBDC issuance and influence its design.

Future monetary systems will likely feature CBDCs, departing from how they predominantly operate and not through the crypto universe, however, with country- or region-specific features. CBDCs of African central banks will carry special features.

References

Alberola, E. and Mattei I. (2022). “Central bank digital currencies in Africa”, BIS Papers no. 128, November.

BAM (2021). « Rapport annuel sur les infrastructures des marchés financiers et les moyens de paiement, leur surveillance et l’Inclusion Financière ».

BAM and MEF (2021). « Rapport annuel de la Stratégie Nationale d’Inclusion Financière ».

BIS (2022a). Annual Economic Report 2022, June.

BIS (2022b). “CBDCs in emerging market economies”, BIS papers no 123, April.

Fuje, H.; Quayyum, S.; and Ouattara, F. (2022). More African Central Banks Are Exploring Digital Currencies, IMF Chart of the Week, June 23.

Kosse, A. and Mattei,I. (2022). “Gaining momentum – results of the 2021 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies”, BIS papers no 125, May.

Stanley, A. (2022). « The ascent of CBDCs », Finance and Development, IMF, September.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, DC, is Senior Fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, non-resident senior fellow at Brookings Institute, and professorial lecturer at George Washington University. Former Vice President and Executive Director at the World Bank, Executive Director at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and Vice President at the Inter-American Development Bank. He was also Deputy Minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance, as well as professor of economics at University of São Paulo (USP) and University of Campinas (UNICAMP).

Tayeb Ghazi is Senior Economist at the Policy Center for the New South (PCNS). He is also a member of the Social and Solidarity Economy Research Group at Cadi Ayyad University and holds a master’s degree in applied finance from the same university. He is currently working on topics related to labour market, education, migration and some aspects of international trade in developing countries.

[1] The CBDC can be designed at two levels, with the central bank at the heart, and additionally private financial service providers interacting with users.

[2] General Directorate of National Security

[3] The National Supervisory Commission for Personal Data Protection

[4] Professional Grouping of Banks in Morocco

[5] General Directorate of Information Systems Security

[6] National Telecommunications Regulatory Agency

[7] National Authority for Financial Intelligence

[8] Moroccan Capital Market Authority

[9] National Authority for Probity, Prevention and the Fight against Corruption