19 April 2018 – Otaviano Canuto

Manufacturing expansion has been a vehicle for job creation, productivity increases, and growth in non-advanced economies since the second half of the last century. First in Latin America, followed by Asia, and a renewal of production systems in Eastern Europe, rising manufacturing levels served as a channel to transfer labour from low-productivity occupations to activities using more modern technologies coming from abroad.

This was facilitated by the easier cross-border transferability of manufacturing technologies relative to other sectors, particularly of labour-intensive segments in the recent era of production fragmentation and value chains. Once certain minimum local conditions were in place, convergence toward productivity levels in frontier countries was relatively faster than in other sectors.

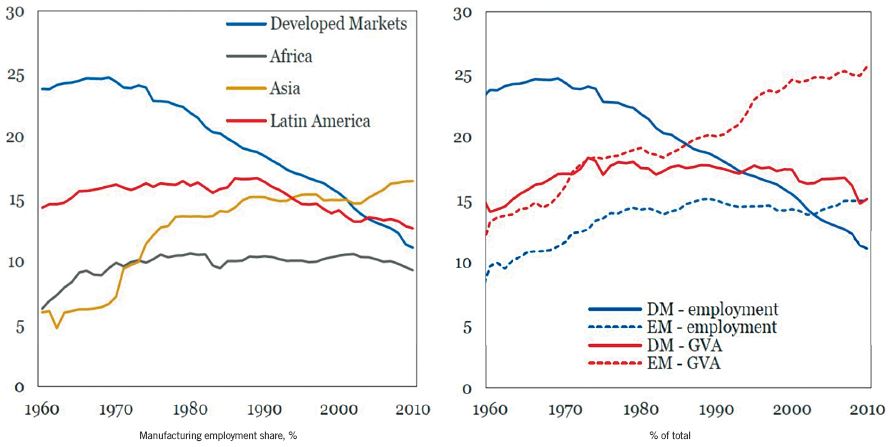

Two issues are now casting a shadow over possibilities of replicating or deepening such a process. First, the very same “footloose” nature of manufacturing also leads to its high sensitivity to minor changes in overall competitiveness factors, such as labour costs, real exchange rates, business environment, infrastructure, and others. Over time, this has led to waves of relocation and spatial concentration in specific countries in the developing world for each of the tiers of sophistication in value chains. Chart 1 depicts the large variation of experiences with manufacturing employment and gross value added between emerging markets.

“There is more complementarity than substitutability between productivity and competitiveness factors between manufacturing and services.”

Second, ongoing technological changes reducing the weight of labour costs are threatening to unwind some of the motivation for transferring manufacturing to non-advanced economies – as we approached in the previous issue of Capital Finance International. The historic recent experience of using manufacturing exports as a platform for high growth will likely become harder to expand, sustain, or obtain in the case among latecomers. At the very least, one may say that the bar in terms of requisites of infrastructure, business environment, local availability of skilled workers, and other competitiveness factors is going up.

Natural resource-based activities offer opportunities for technological upgrades, productivity increases, exports and – volatile but positive – economic growth, but not the massive job creation of manufacturing. As such, a question increasingly asked is whether services could eventually foot the bill in terms of quantity and quality of job creation in developing countries. Would ongoing technological changes lead to higher transferability of technologies and tradability of services? To what extent local manufacturing bases would still matter as a precondition for production of services?

Chart 1: Manufacturing employment and gross value added. Note: DM = Developed Markets; EM = Emerging Markets; GVA = gross value added. Source: IIF, A Primer on Premature Deindustrialization, October 19, 2017.

Those are among the questions approached by Mary Hallward-Driemeier and Gaurav Nayyar (2017, Trouble in the making? ISBN: 9781 4648 1174 6). They call attention to how advances in information and communications technologies (ICT) have made some services – financial, telecommunications, and business services – increasingly tradable. That process has been making feasible the diffusion of technology and the possibility of exporting in addition to attending local demands.

The authors also highlight the high potential of reaping economies of scale in those services highly impacted by ICT, especially as very low marginal costs are incurred by adding units to production. R&D intensity has risen, with as an example, expenditure in business services rising close to 17% in 2005-10 from 6.7% in 1990-95.

On the one side, like manufacturing, opportunities for local technology learning and raising productivity in developing economies may be created by increasing international tradability and technology transferability. On the other, unlike labour-intensive manufacturing, those services are not expected to be a strong source of jobs for unskilled labor.

The low-end services that remain users of unskilled labour are less likely to create opportunities of productivity gains. With exceptions – the authors mention construction and tourism services – there is less scope in the services sector to yield simultaneously high productivity increases and job creation for unskilled labour, at least as compared to what manufacturing-led development provided in previous decades.

How about the connection between manufacturing and services? Besides the increases of demand for stand-alone services with high income elasticity, what are the prospects for the demand for services accompanying the current transformation of manufacturing? To what extent supply and demand for these manufacturing-related services benefit from local manufacturing bases?

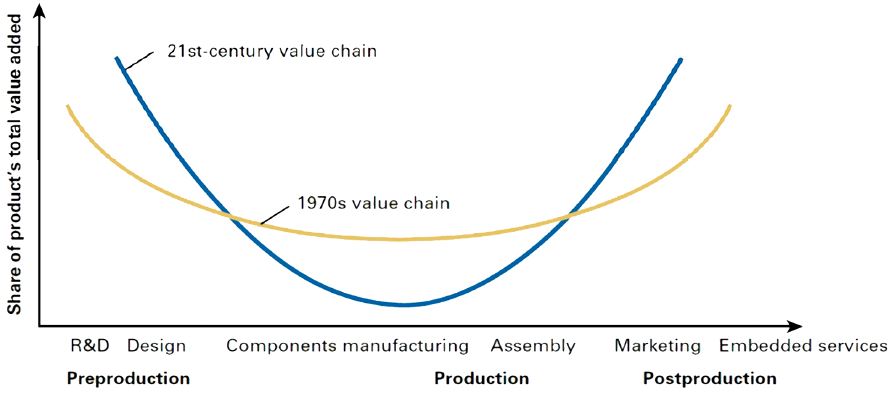

Chart 2: Value Added of Services in Manufacturing, 1970s versus 21st Century. Source: Hallward-Driemeier, M. and Nayyar, G. “Trouble in the Making?: The Future of Manufacturing-Led Development”, World Bank, Washington D.C., 2017.

Hallward-Driemeier and Nayyar call attention to the rising “servicification” of manufacturing, as the latter is increasingly “embodying” and “embedding” services, while the share of component manufacturing and final assembly in value added declines (see chart 2).

The relevance of embodied services in manufacturing products has risen either as inputs (design, marketing, distribution costs, etc.) or as trade enablers (logistics services or e-commerce platforms). Furthermore, services are also increasing embedding facilities that come bundled with, or are added to, manufactured products. They point out apps for mobile devices and software solutions for “smart” factories. They conclude (p.162):

While a range of “stand-alone” services and some embedded services can provide growth opportunities without a manufacturing core, the increasing servicification of manufacturing underscores the growing interdependence between the two sectors. Given this deepening interdependence, policies that improve productivity across different parts of the value chain will result in the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. The agenda therefore should be to prepare countries to use synergies across sectors to participate in the entire value chain of a product while also exploiting stand-alone opportunities beyond manufacturing.

In sum, the challenges to achieve, simultaneously, the employment of unskilled workers and substantial increases in productivity are becoming taller. Furthermore, those horizontal productivity and competitiveness factors – including local accumulation of capabilities, low transaction costs, infrastructure improvement, etc. – that were crucial for a broad and deep manufacturing-led development are now extended to services. There is more complementarity than substitutability between productivity and competitiveness factors between manufacturing and services. There is no alternative but to raise the bar domestically if a developing country wants to enjoy any of these as engines of growth.

First appeared at Capital Finance International