Otaviano Canuto and Márcio Issao Nakane

First appeared as a Policy Brief at Policy Center for the New South

Also at Seeking Alpha and TheStreet.com

Brazil is one of the countries hardest hit by COVID-19. Apart from the dramatic health implications, COVID-19 will also scar the Brazilian economy, including through a jump in its already high public-sector debt-to-GDP ratio in 2020. Moving forward—or not—with structural reforms aimed at lifting private investment will define whether a sustainable—or unsustainable—growth-cum-debt trajectory will prevail in the next decade. The extent to which Brazil regains its attractiveness for foreign investors will play a key role.

COVID-19 has significantly hit Brazil’s economy, leading to substantial gross domestic product (GDP) decline in 2020. The country’s post-pandemic GDP trajectory for the next decade will be at levels below what was expected prior to COVID-19.

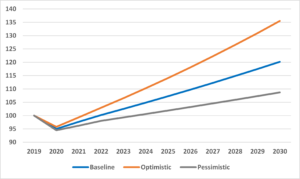

Figure 1 shows the November 2020 GDP forecasts of the Brazilian Senate’s Independent Fiscal Institution (IFI, 2020). As a baseline forecast, GDP is expected to fall by 5.0% in 2020, only partially recovered with a 2.8% growth rate in 2021. GDP is predicted to return to the pre-COVID-19 level only in 2022.

Depending on the length of the still unfolding pandemic and its impact on the economy, and on the effectiveness of the policies so far implemented to flatten the recession curve, optimistic and pessimistic GDP growth scenarios are also offered: -4.2% and 3.7% for 2020 and 2021 respectively in the optimistic scenario, and -5.5% and 1.8% for 2020 and 2021 respectively in the pessimistic scenario.

The December 4 expectations survey carried out by the Brazilian Central Bank reveals that market participants expect GDP growth of -4.4% and 3.5% for 2020 and 2021 respectively. These figures are closer to the upper optimistic interval reported by the IFI than to its baseline scenario, signaling that market participants expect faster economic recovery from the pandemic shock.

In the baseline scenario, the annual potential GDP growth rate for 2023-30 is estimated by the IFI at 2.3%, with the inflation rate and basic real interest rates assumed to converge to 3.5% per year and 3.0% per year respectively. Such figures are lifted (downgraded) in the optimistic (pessimistic) scenarios, depending on how favorably (unfavorably) country-risk premiums affect exchange rates, inflation, and real interest rates (Figure 1).

In the optimistic scenario, the annual potential GDP growth rate for 2023-30 is raised to 3.5%, with the inflation rate and basic real interest rates predicted to converge to the lower levels (compared to the baseline) of 3.2% per year and 2.4% per year respectively.

In contrast, in the pessimistic scenario the annual potential GDP growth rate for 2023-30 would be only 1.3%, with the inflation rate and basic real interest rates supposed to rise to the higher values (compared to the baseline) of 4.5% per year and 5.1% per year respectively.

Figure 1: Brazilian GDP (2019=100)

Source: IFI (2020).

Thus, the different scenarios for GDP growth depicted in Figure 1 encompass not only contrasting views about the short-term trajectory of the Brazilian economy (2020-22) but also distinctly different perspectives related to the country’s potential GDP growth over the medium and long terms (2023-2030).

The extent and length of the various waves of the COVID-19 shock, the public policy responses (monetary and fiscal measures), the lockdown measures put in place by the authorities, the population’s compliance with such measures, and the resumption of economic activity are all important factors for the short-term resolution for the GDP path undertaken by the country.

Over the medium to long term, on the other hand, more structural issues come to the forefront. The fragile fiscal situation, the resumption of much-needed investment, a more favorable business climate, structural reforms, and attraction of foreign direct investment flows are the main challenges that will shape the performance of the country’s growth potential over the next decade.

A Fiscal Crossroads

The evolution of the country-risk premium and, therefore, of the public debt-to-GDP ratio will ultimately define which trajectory Brazil’s GDP follows. As in most countries, anti-catastrophe public policies taken to flatten the recession curve, together with a fall in tax revenues, will—temporarily but intensively—raise the public sector nominal deficit. The combination of a GDP decline and a high public deficit will have, by the end of 2020, significantly lifted the level of public debt as a proportion of GDP. As a result, even assuming a return to the pre-COVID-19 fiscal framework—including the constitutionally mandated federal government spending cap—Brazil will face a fiscal adjustment challenge steeper than before the pandemic.

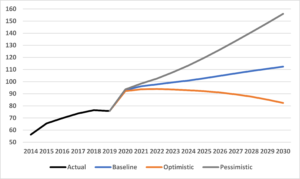

The IFI report also offers three scenarios for the nominal public deficit in 2020 and, correspondingly, the increase in the General Government Public Debt (GGPD) to GDP ratio at the end of 2020. Furthermore, based on the assumptions on country-risk premium, exchange rates, and real interest rates used in the GDP projections, three paths for the GGPD-GDP ratio are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: GGPD as % of GDP

Source: IFI (2020).

The jump in the public debt-to-GDP ratio in 2020 will be a staggering 17.27 percentage points of GDP according to the IFI baseline scenario. The fiscal measures related to the pandemic will reach 7 p.p. of GDP in 2020 in the baseline case. The fiscal primary deficit will rise to 10.9% of GDP in 2020, a record-breaking level. Prior to that, the highest recorded value for the fiscal primary deficit was 2.5% of GDP in 2016.

In the IFI baseline scenario, the public debt-to-GDP ratio would stabilize three to four years after 2030. The landmark value of 100% of GDP would be reached in 2024 and the public debt-to-GDP ratio would keep rising, reaching 112.4% of GDP in 2030. In the optimistic scenario, the public debt-to-GDP ratio would peak at 93.9% by 2022, declining to 82% by 2030. The pessimistic scenario, in turn, points to an insolvency route for the public debt-to-GDP ratio.

In the baseline case, Brazil is expected to register fiscal primary deficits until 2030 in line with an improving path from 2.9% of GDP in 2021 to 0.8% of GDP in 2030. Only the optimistic scenario contemplates paths with fiscal primary surpluses starting in 2026. In that year, Brazil will produce a primary surplus of 0.18% of GDP, which would keep increasing up to 1.92% of GDP in 2030, according to the IFI optimistic case.

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate the post-pandemic fiscal crossroads at which Brazil will find itself, particularly as the evolution of public debt and corresponding risk premia will establish feedback loops with GDP throughout the next decade. Either there will be stagnation and insolvency, or a gradual fiscal adjustment and better growth prospects.

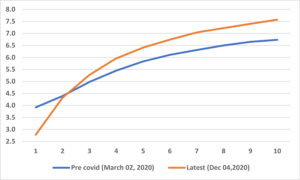

The uncertainty related to the fiscal stance for the coming years can be gauged by the behavior of long-term interest rates in Brazil. Figure 3 shows the interest rate for public bonds at different maturities (in years) for two moments: before COVID-19 hit (March 2, 2020) and the latest curve at time of writing (December 4, 2020).

Monetary policy easing, which saw the basic interest rate (Selic) fall from 4.25% per year in early March to 2% per year, has shifted downward the interest rate curve at short maturities. However, the steeper slope caused by spikes in the longer maturities reflects the uncertainties surrounding the sustainability of fiscal policies in the coming years. The interest rate on 10-year public bonds shows an increase of 0.85 p.p. compared to the pre-COVID-19 situation.

Figure 3: Term Structure of Interest Rates in Brazil (% per year)

Source: B3.

The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened the already fragile fiscal position faced by Brazil. The rising public debt-to-GDP ratio makes the country’s public debt trajectory quite sensitive to the underlying conditions related to the paths of interest rates, fiscal primary surplus, and GDP growth. The public debt-to-GDP ratio will be balanced on a razor’s edge over the next years. Any slight change in the paths for interest rates, fiscal primary surplus, or GDP growth will have dramatic effects on public debt-to-GDP movements, causing the ratio to oscillate between more sustainable and unsustainable routes. More uncertain times lie ahead in the fiscal front.

As well as returning to a credible fiscal adjustment path, structural reforms aimed at boosting private investment will also matter for the growth-cum-debt trajectory. The multi-year horizon of infrastructure investment decisions, i.e. going beyond the dire short-term economic prospects, makes the participation of the private sector an opportunity to circumvent the lack of fiscal space in the decade ahead. Higher infrastructure and other long-term investment would improve both aggregate demand and productivity. For that to happen, though, the structural reform agenda—tax, business environment, sector regulation fine tuning—must be prioritized.

The Two Sides of Capital Flows to Brazil

Attention should also be paid to the link between such structural reforms and private investments, and the change in the size and profile of foreign capital flows to Brazil in the recent past. Although a positive current-account balance is expected in 2020, the tendency is towards deficits. Capital inflows have more than compensated for those deficits in the recent past and, in fact, they are responsible for the significant accumulation of foreign reserves by Brazil since the mid-2000s, which underlies its solid external accounts position. Besides their implications for exchange rates and domestic financial conditions, such capital inflows have been a positive factor for investment in the Brazilian economy.

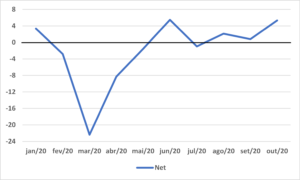

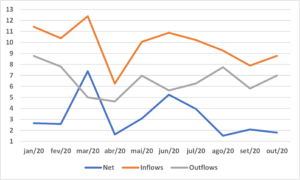

Now, there has been a change of signal in the Brazilian capital account of the balance of payments, particularly since Brazil lost its investment grade back in 2015. Equity and fixed-income flows have become negative since the 2015-16 recession, and the transition to lower domestic interest rates has diminished the country’s role as a yield provider (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Balance of Payments – Portfolio Investment – Accumulated 12 months (US$ billions)

Source: Central Bank of Brazil.

The portfolio investment account for 2020 remains in the red (Figure 5). The substantial departure in March and April, reflecting the tremendous shock that COVID-19 caused to global financial markets, has not yet been fully offset by inflows since June. But, for some, the recent figures gave rise to a feeling that the improvement in international financial conditions was sufficient to guarantee stability on the external front.

Figure 5 – Portfolio Investment – Net flows in 2020 (US$ billions)

Source: Central Bank of Brazil.

The external inflow was even an important factor in Brazil’s equity index (Ibovespa) registering an increase of 15.9% in November 2020 (over the previous month), which reduced the accumulated fall in 2020 to 5.84%. When converted to dollars, due to the appreciation of the real currency in the month, the appreciation was almost 25%, making the Brazilian stock exchange the best performing compared to other emerging economies and the three largest Wall Street indices (S&P 500, Nasdaq, and Dow Jones). It is also worth noting that the share of foreign investors holding domestic public debt securities rose from 9.44% to 9.79% in October 2020.

What now? Were those who drew so much attention to the need for advances on the domestic policy side exaggerating, by emphasizing that the approval of reforms that facilitate compliance with the public spending ceiling would be a precondition for relying on foreign financial resources in the recovery of Brazilian economic growth?

The truth is that capital flows to emerging economies respond to both external, more general, factors, and to domestic, country-specific factors and impulses. They are always the result of a combination of both. This implies recognition that, at the limit, domestic factors make the difference that makes each country unique. In the current Brazilian scenario, it is not possible to fully rely only on the evolution of international financial conditions.

When looking at outside conditions, news of effective COVID-19 vaccines with lower logistical requirements has fueled optimism about the future of the global economy, despite fears about waves of contamination until those vaccines are widely applied. However, as is the case in such circumstances of mood improvement, the appetite for taking risks has increased, particularly given the prospect of prolonged low rates of return in low-risk applications (Canuto, 2020). The outcome of the elections in the United States has also contributed to this, by promising an end to the uncertainties of the Trump era.

Thus, in November 2020, there was a rush towards assets in emerging economies, followed by another for stocks and debt securities in the United States. In emerging markets, there was a clear return to the situation prior to the COVID-19 financial shock and the capital flight in March.

Emerging stock funds attracted nearly $14 billion in the second and third weeks of November 2020, while $22 billion moved to buy stocks in those countries during that month. Debt securities from those countries also saw high demand.

The appetite for risk and the prospect of improvement in the global economy were manifested in a portfolio rotation, with higher demand for energy and financial services in relation to assets already valued by Wall Street. The Brazilian stock exchange as a destination benefited from the fact that it has banks, Vale and Petrobrás, as main stocks.

There is also an expectation that the dollar will gradually devalue against other currencies. This not only tends to raise dividends and interest earned in local currencies with emerging assets in dollars, but also facilitates the payment of debt commitments abroad by governments and companies in those countries. Just remember the hardships suffered by some—such as Argentina and Turkey in 2018—in times of appreciation of the dollar.

Clearly, it remains possible that, at some point, the Federal Reserve will be urged to raise interest rates and/or undo its quantitative easing program (QE). The simple possibility could generate a new ‘taper tantrum’, similar to that of 2013, when the mere announcement by the Fed that it was planning to exit QE caused a huge outflow of capital from emerging countries with current account deficits, including Brazil. In any case, this is not being considered as likely soon.

How about the country-specific side in the Brazilian case? First, it should be noted that the bulk of the recent inflow has arrived in a ‘passive’ way, that is, as a component of funds that seek exposure to emerging assets in general, a group in which Brazil occupies a significant global position despite changes in recent indexes. As an increasing volume of resources in the global financial markets has been driven by exchange-traded funds (ETFs), it happens that, in relative terms, lower-quality assets (lower-rated sovereign bonds, less-liquid stock markets etc.) undergo more positive and negative impacts than others in situations of increase and decrease respectively in the size of ETFs.

Therefore, the partial return of portfolio capital to Brazil in the last few months of 2020 must not be confounded with a return to previous conditions. Rather it reflects a partial unwinding of the overshooting in portfolio adjustments to the global financial shock in March.

In addition, the recent inflow of capital to Brazil has not included considerable volumes from ‘active’ investors, that is, those who look directly at specific assets. For these, country-specific domestic determinants weigh more. For the ongoing positive wave to be seen in the availability of external resources to finance investments in Brazil, progress and confidence in the domestic fiscal and regulatory agenda will be relevant.

Foreign direct investment in Brazil in 2020 has been weak (Figure 6). FDI net flows reached a peak in March ($7.4 billions) but the amounts have remained around the $2 billion mark since August.

Figure 6: Foreign Direct Investment, Flows in 2020 ($ billions)

Source: Central Bank of Brazil.

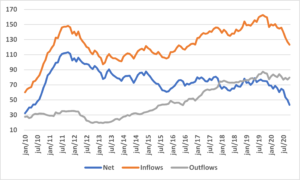

Thus, foreign direct investment is not likely to fill the void soon in the absence of new opportunities. From a longer perspective, Figure 7 shows that 12-month accumulated FDI net flows have been stagnant since 2015, despite increased gross inflows. During the COVID-19 pandemic, FDI inflows took a huge drop with no recovery yet in sight.

Figure 7: Balance of Payments, FDI, Accumulated 12 Months ($ billions)

Source: Central Bank of Brazil.

Resumption of foreign direct investment is key for Brazil to resume sustainable growth. The participation of foreign capital in infrastructure investment through public-private partnerships would be convenient, as fiscal space for public investments will continue to be tight in the coming years. As the inflow of funds is no longer obtained by offering high interest premiums on public debt, a full return of FDI will have to occur with exposure to assets different from coupon-yielding bonds. The Brazilian economy finds itself at a crossroads, with possible positive or negative trajectories in the interaction between risk premiums, interest rate, public debt, and GDP. Foreign capital inflows or outflows will reinforce, respectively, positive and negative trajectories.

Therefore, a combination of a credible return to the fiscal adjustment path and investment-friendly structural reforms would also have an additional positive effect of making possible new rounds of foreign capital inflows. That would increase the likelihood of an eventual optimistic growth-cum-debt scenario for the Brazilian economy

References

Canuto, O. Whither Interest Rates in Advanced Economies: Low for Long?, Policy Center for the New South, October 23, 2020.

Instituição Fiscal Independente (2020). Relatório de Acompanhamento Fiscal, Number 46, November 16, 2020, Brasília. (available online at https://www2.senado.leg.br/bdsf/bitstream/handle/id/579879/RAF46_NOV2020.pdf)

————————–

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, and principal of the Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank.

Márcio Issao Nakane is assistant professor at the Economics Department, University of Sao Paulo.