Policy Center for the New South, Seeking Alpha, TheStreet.com, Capital Finance International

In addition to the deaths and destruction in Ukraine, the Russian invasion has caused several significant shocks to the global economy. In addition to the geopolitical consequences of the war, reinforcing the downward trend in trade globalization and financial integration, new rounds of disruptions to supply chains and higher commodity prices have already led to downward revisions in economic growth projections, accompanied by higher inflation.

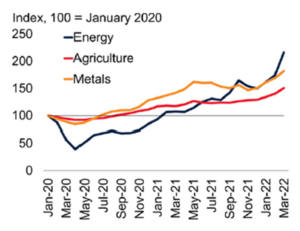

The commodity price shock, intensifying trends that have been present since mid-2020, has already led to significantly higher price levels in so far 2022. Higher prices will remain in the medium term, according to the World Bank’s Commodity Markets Outlook report, issued on April 26 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Commodity Prices

Source: World Bank (2022). Commodity Markets Outlook, April.

The outlook for commodity markets will depend on how long the war in Ukraine lasts, the sanctions imposed on Russia, and the severity of disruptions to commodity flows. Russia and Ukraine are both major suppliers of energy, fertilizers, some grains, and metals. Russia is the world’s biggest exporter of natural gas, nickel, and wheat, while Ukraine is the biggest exporter of sunflower oil. Not coincidentally, these commodities have experienced particularly sharp increases since the start of the war in Ukraine.

Several countries, including the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom, have already announced bans or phase outs for Russian oil imports, while private buyers have also pledged to cut purchases of Russian oil. What about supply alternatives? One problem, as observed in a study by the Federal Reserve of Dallas, is that production capacity restrictions in OPEC+ member countries are preventing them from even fulfilling their quotas assigned by the organization.

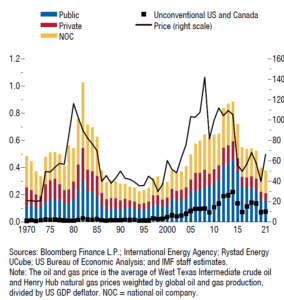

The International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook report, released on April 19, suggested that anticipation of falling demand for fossil fuels—due, among other things, to the energy transition—has reduced global investment in oil and gas by about 20% in the last three or four months. After spiking during the ‘shale revolution’, global upstream oil and gas investment peaked at 0.9% of global GDP in 2014, falling to less than 0.5% of global GDP in 2019, and dropping further during the pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Oil and Gas Investment as Share of World GDP (%, US$/barrel)

The price of Brent crude reached an average of $116 per barrel in March, something not seen since 2013. The World Bank forecasts that average oil prices will average $100/barrel this year, before declining smoothly to $92 a barrel in 2023.

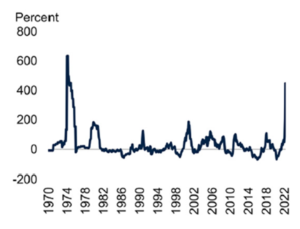

In March, European natural gas prices were almost seven times higher than one year before. Coal prices in several parts of the world have also tripled as a result of expected disruptions to Russian natural gas and coal exports. The post-pandemic demand recovery and restricted supply conditions were already having an upward effect, but the new jumps made the increase in energy prices in the last two years the biggest in the last half century, since the oil shock in 1973 (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Energy Price Growth

Source: World Bank (2022). Commodity Markets Outlook, April.

The permanence of prices at higher levels will be reinforced by two factors. First, as prices of all fossil fuels are increasing, there is not much scope to replace the most affected energy commodities with other fossil fuels. Second, energy commodities have a strong influence on the prices of other commodities. For example, natural gas prices have already pushed up fertilizer prices, putting pressure on agricultural prices.

In the case of food, trade disruptions and high input costs have also had a significant impact. The UN food price index placed food prices at the highest level since tracking started 60 years ago. It’s not just higher wheat prices because of the war. Lower-than-usual wheat and soybean crops in South America has also negatively affected their global availability.

Higher prices and risks of fertilizer shortages are sources of concern for food prices next year. Food security and possible social upheavals have become central issues in parts of the world, including countries in Africa, Middle East, and Asia that are among the poorest and most reliant on food imports.

Prices of some metals also reached unprecedented levels in March, due to risks of supply disruption, while inventories were at historically low levels. Ukraine and Russia are substantial sources of palladium and platinum, both of which are used in the manufacture of catalytic converters for the automobile industry. Platinum, copper, and nickel are critical inputs for electric vehicle batteries. Ukraine is also the source of 50% of the world’s neon gas, used for lasers used to manufacture semiconductor chips.

The war in Ukraine has been the main driver of aluminum and nickel price movements, while high energy prices have in turn affected zinc. These metals are key inputs in renewable technologies such as solar panels and wind turbines. As a result, further price increases, or interruptions in the supply of these metals, could make the energy transition more expensive.

In the short term, the macroeconomic impacts of the commodity price shock will differ among emerging economies, depending on whether they are exporters or importers. In Latin America, for instance, there is a new inflationary spike, while exporters tend to benefit in terms of GDP, trade balances, and public sector accounts. Brazil’s growth projection was slightly increased by the IMF to 0.8% and 1.3%, respectively, for 2022 and 2023.

Strictly speaking, the war in Ukraine and the shock to energy commodity prices have not been favorable to the energy transition, as seen in the race for coal and new sources of oil. This comes on top of the pandemic, which is not yet over, as will be seen in the coming weeks in the global consequences of the lockdowns in China, resulting from its quest for zero-COVID-19. For the recent combination of pandemic plague, war, and deaths not to assume apocalyptical proportions, the world must prevent more extreme climate change brought about by further delays to the energy transition.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil.