The landscape of international trade negotiations has been undergoing an upheaval. On the multilateral level, after 15 years of unsuccessful attempts to close the Doha Development Round at the World Trade Organization (WTO), the negotiation system has shown to be highly vulnerable to blockades by any small group of member countries. The complex web of diverse individual country objectives, cutting across several interrelated themes, made reaching a deal harder than originally expected. However, even when the scope was narrowed to a trade facilitation negotiation, as the one concluded in Bali in December 2013, it has yet failed to yield results.

In the meantime, after the proliferation of preferential trade agreements (PTAs) in the world, the U.S. and the EU have decided to embark on so-called mega-trade negotiations. After the U.S. proposed a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) with several countries of the Pacific region, the EU has accepted to negotiate a Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) with the United States. From a diplomatic perspective, taking such an approach offers a way to overcome the difficulties in reaching consensus/compromise in the multilateral arena.

At the same time, there is also the fact that large and rich negotiators have found a way to reinforce their asymmetric positions and agenda-setting capacity that tend otherwise to be partially diluted in multilateral, 100-percent-based negotiation tracks.

By design, those mega-negotiations have a scope that goes much beyond tariff and non-tariff barriers to trade to encompass rules for trade-related issues such as investment and competition, as well as new themes like environment, climate change, labor regulation, and other issues.

The inclusion of these sectoral issues in multilateral negotiations has faced tough resistance.

It is also relevant that the weight of different barriers to trade has changed in the last few decades (Canuto, 2012a). As tariffs have on average been reduced, and as “value chains” and cross-border trade of services have flourished, regulatory divergence and non-tariff trade barriers have risen in relevance as trade-binding factors — together with logistics constraints in many countries (Canuto, 2012b; 2013). That is why recent estimates of the potential impact of TTIP on EU countries show more meaningful results in scenarios where non-trade barriers are trimmed (see Felbermayr et al. 2013).

Provided that meaningful content can be agreed upon, the size of the economies engaged in those mega-trade negotiations guarantees that outside countries will also be strongly impacted. There will be direct, first-order trade-deviation effects on exports and imports of goods and services, as countries not part of the negotiations will face preferences acquired by beneficiaries inside agreements. Furthermore, there will be second-order effects derived from subsequent competitiveness changes in those countries’ inside agreements, as they will more readily attract investment and technology flows.

Take Brazil, a relatively small global trader that has concentrated its bets on the multilateral arena. This has been illustrated by a series of simulations reported by Vera Thorstensen and Lucas Ferraz from the Getulio Vargas Foundation, on what would be the first-order impacts of TTIP and TPP on Brazil under different hypotheses of coverage of these agreements (see Thorstensen and Ferraz 2014).

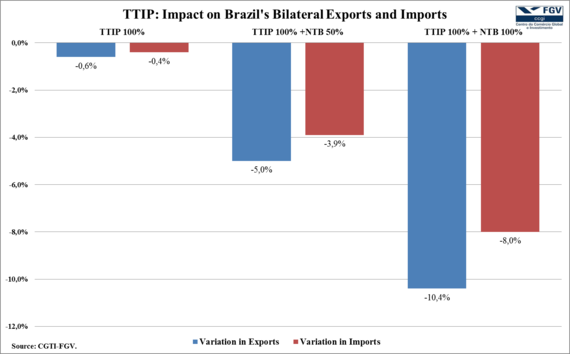

Chart 1 displays their aggregate results in terms of first-order impacts of TTIP on Brazil’s bilateral trade with the U.S. and the EU, under three scenarios of completion of the agreement: (1) full tariff elimination between the EU and the U.S. (TTIP 100 percent); (2) the previous plus a 50-percent reduction of non-tariff barriers (TTIP 100 percent + NTB 50 percent); and (3) full elimination of both tariffs and non-tariff barriers (TTIP 100 percent + NTB 100 percent). Consistently with what we have noted above regarding current relative weights of tariffs and non-tariff barriers, as well as estimates of impacts of their elimination, first-order impacts on Brazil’s exports and imports — and corresponding negative consequences to the trade balance — rise in significance as non-tariff barriers between the EU and the U.S. are lowered.

Extracted from Thorstensen and Ferraz 2014

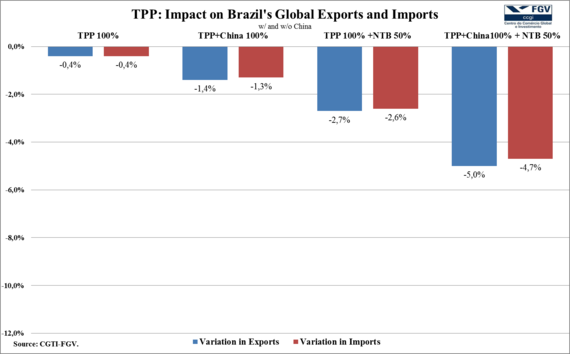

Chart 2 shows the authors’ results in terms of first-order impacts of TPP on Brazil’s total exports and imports. In addition to scenarios of full tariff elimination with and without a 50-percent reduction of non-tariff barriers, they also explored the hypothesis of China’s participation in the agreement. One may notice again how the magnitude of impacts rises with the coverage of non-tariff barriers, particularly if China enters TPP.

Extracted from Thorstensen and Ferraz 2014

The authors also simulate the case of Brazil adhering to TTIP. Brazil’s exports, imports, and the trade balance are then positively affected, with gains particularly accrued by agricultural sectors.

Let me offer two takeaways. First, although negative first-order impacts of TTIP and TPP on Brazil’s trade may look non-dramatic, one should not lose sight of the fact that they tend to be reinforced by subsequent competitiveness improvements in the economies participating in the agreements. This comes in addition to the opportunity costs already incurred by Brazil because of its trade closedness (Canuto (2014), Canuto et al. 2015a;2015b), especially as investment and technology flows tend to be diverted as a reflection of those mega-trade agreements.

The potential impact of mega-trade agreements goes beyond how they affect trade, since exposure to increased competition at home and the impact of such a deals on export destinations and in third markets can boost productivity growth and improve competitiveness. This applies not only to tradable sectors, but also to non-tradable activities in participating economies.

Second, and relatedly, Brazil might well review its prevailing trade negotiation strategy where efforts have focused on the multilateral track. Bilateral trade agendas with both U.S. and EU may become a way to mitigate the negative potential impacts of TTIP and TTP.

Otaviano Canuto is a Senior Adviser and ex-Vice President at the World Bank. All opinions expressed here are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the World Bank.

First appeared at Huffington Post and Roubini EconoMonitor