Policy Center for the New South, Policy Paper PP – 01/24

Center for Social and Economic Progress

Seeking Alpha, TheStreet.com

Otaviano Canuto and Amshika Amar

*The authors wish to thank Abdelaaziz Ait Ali for comments on an earlier version, without implicating him in any way.

INTRODUCTION

When countries face external financial shocks, they must rely on financial buffers to counter such shocks. The global financial safety net is the set of institutions and arrangements that give economies layers of defense against such shocks.

From any individual country standpoint, there are three layers or lines of defense in their external financial safety nets (Iancu et al, 2021). The first is the countries’ own international reserves. A second line of defense comes from pooling resources with other countries. Bilateral swap lines, whereby central banks exchange currencies to provide liquidity to financial markets, is a potential protective layer. Additionally, plurilateral—regional or not— financing arrangements, by which countries pool resources to respond to financing needs in a shock, also offer a line of defense. Finally, there is the International Monetary Fund (IMF), as a multilateral lender of resort.

The second line of defense—swap lines and plurilateral financing arrangements—has been enhanced over the past two decades. However, this protection remains available only to a small group of countries.

We argue here that there is a need to extend and facilitate access to the ultimate global financial safety net layer—the IMF. We illustrate this by pointing out how Morocco and Mexico have boosted their defensive power by having access to IMF precautionary lines of credit.

International Reserves are the First Line of External Financial Defense

A country’s international reserves are its first line of defense. Holding international reserves is costly, as their asset returns are low. Their non-use to obtain alternative types of assets corresponds to an opportunity cost, one that is in principle justified by the gains from protection against shocks and stoppage of transactions. A very hard-to-answer question is what the optimal levels of reserves are in order to maintain a balance between such costs and benefits (Saraiva and Canuto, 2009).

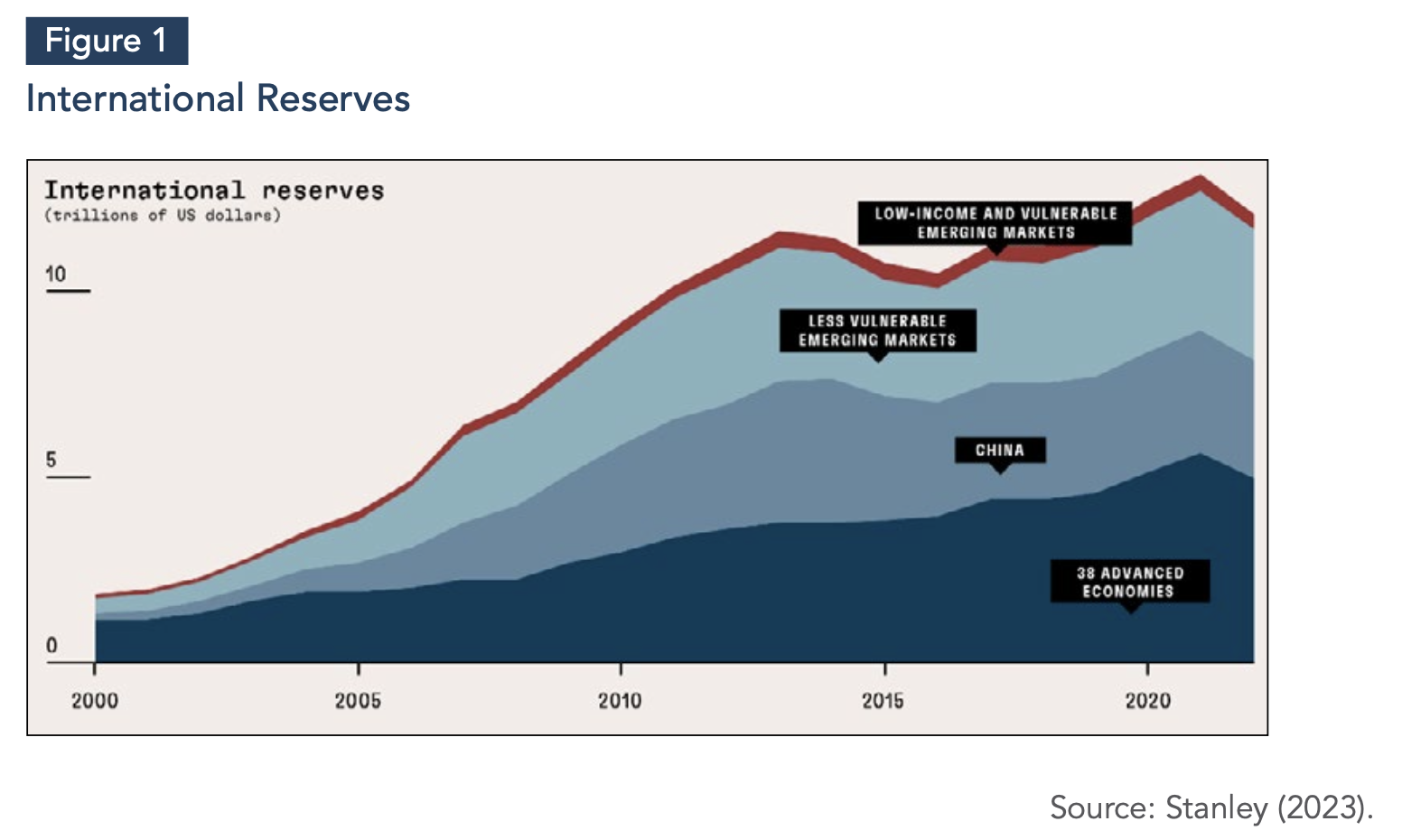

Countries’ international reserves have grown in volume recently, after a dip in the second half of the 2010s (Figure 1). However, the aggregate numbers hide a very variable picture among individual countries. As pointed out by Stanley (2023), 97% of those reserves have been accumulated by approximately 50% of countries, whereas around 90 emerging market and low-income countries account for the remaining 3% or reserves. While many emerging market economies substantially increased their international reserves in the 2000s (Canuto and Cavallari, 2017), that has not been the case of most low-income countries.

Pooling Resources Constitutes a Second Line of Defense

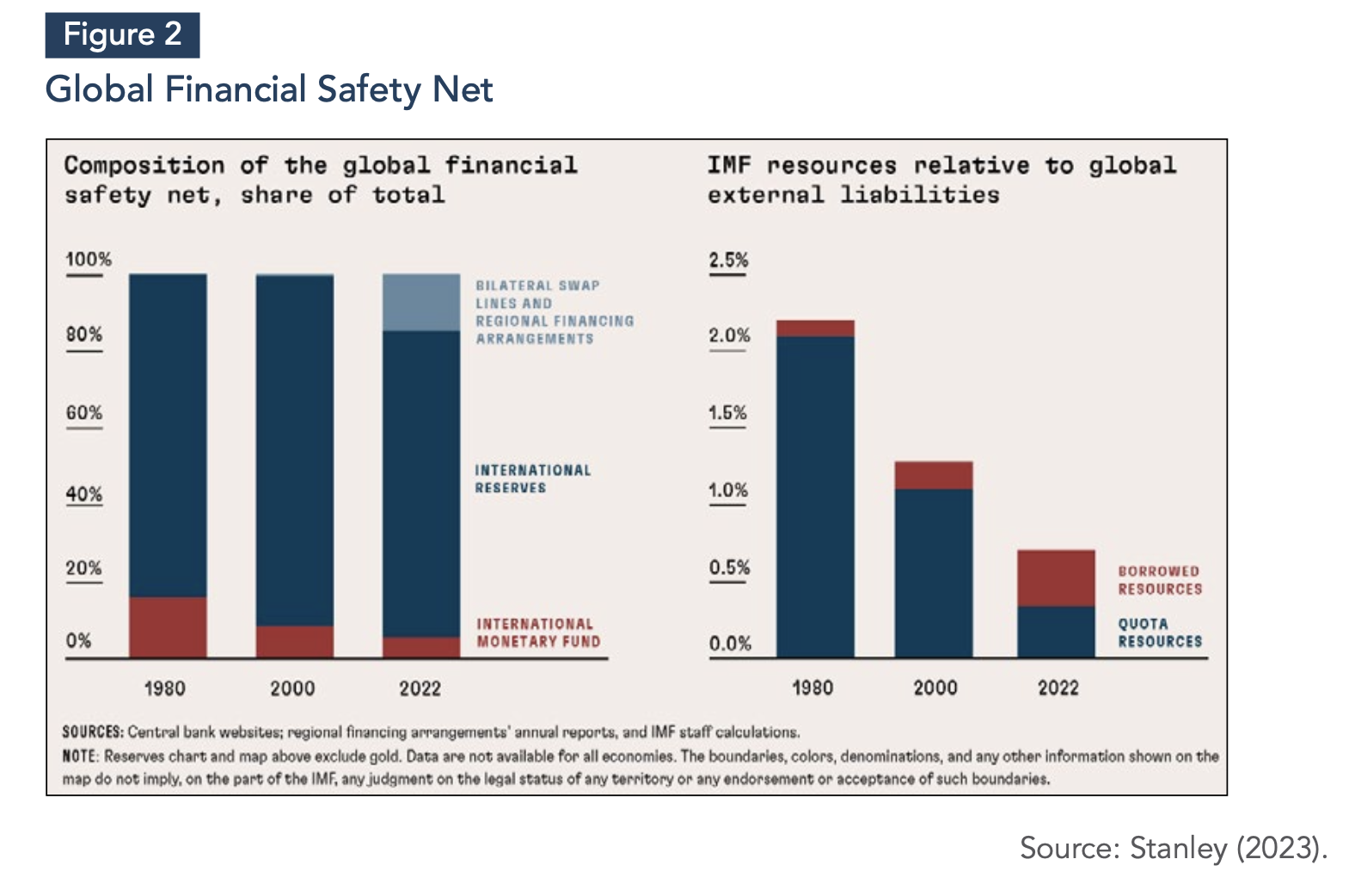

Pooling resources—via bilateral swap lines and regional or plurilateral arrangements—is an additional shield against shocks. Swap lines are arrangements that are designed to improve liquidity conditions and help ease strain in financial markets. They support financial stability and serve as a prudent liquidity backstop (Figure 2).

Let us illustrate the increased weight of this second line of defense by looking at the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB). The U.S. Federal Reserve operates dollar swap lines with the following central banks: Reserve Bank of Australia, the Bank of Canada, Danmarks Nationalbank, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of Korea, the Banco de Mexico, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Norges Bank, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, Sveriges Riksbank, and the Swiss National Bank. The highest dollar transaction through swap lines is with the ECB ($814 billion). The only emerging market with such a transaction is Mexico ($15 billion). Most swap lines were used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Let us illustrate the increased weight of this second line of defense by looking at the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB). The U.S. Federal Reserve operates dollar swap lines with the following central banks: Reserve Bank of Australia, the Bank of Canada, Danmarks Nationalbank, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, the Bank of Korea, the Banco de Mexico, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, Norges Bank, the Monetary Authority of Singapore, Sveriges Riksbank, and the Swiss National Bank. The highest dollar transaction through swap lines is with the ECB ($814 billion). The only emerging market with such a transaction is Mexico ($15 billion). Most swap lines were used during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Federal Reserve also operates foreign-currency liquidity swap lines with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank.

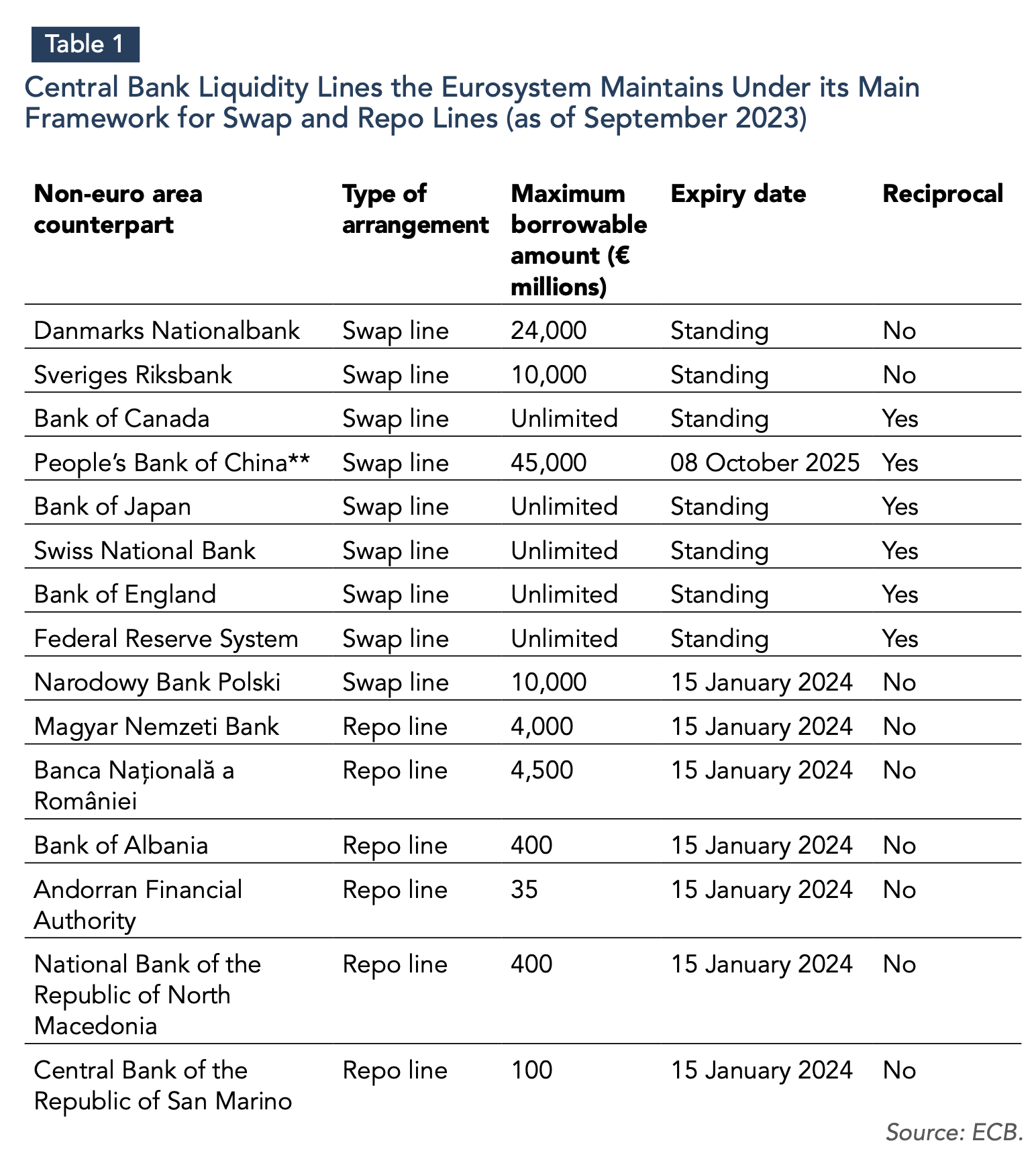

The ECB, meanwhile, is part of a swap-line network of standing bilateral arrangements with five other major central banks (the Bank of Canada, the Bank of Japan, the Swiss National Bank, the Bank of England, and the Federal Reserve System). The ECB has increasingly used swap and repo lines since the 2008-09 global financial crisis.

The ECB provides euro against foreign currencies, which are accepted as collateral. Under reciprocal swap lines, the ECB may also receive foreign currencies by providing euro as collateral. Under the repurchase agreements, the ECB provides euros to non-euro area central banks and receives euro-denominated financial assets as collateral.

These swap and repo lines help meet the liquidity needs of euro and non-euro countries to prevent spillback effects that might have an adverse impact on the smooth transmission of the ECB’s monetary policy from impacting on euro-area financial markets and economies. The ECB uses a strict set of criteria when deciding whether to grant swap and repo lines to non-euro central banks. In June 2020, the ECB established a temporary Eurosystem repo facility for central banks (EUREP), which aims to broaden access beyond the swap and repo lines (Table 1).

As shown by Figure 2, the second line of defense has emerged since the turn of the millennium. But like international reserves, swap lines are out of reach for many emerging market and developing economies. Also, the relative size of the IMF has diminished, including relative to global external liabilities (Figure 2, right panel).

While advanced economies have established such bilateral swap lines between their central banks to boost their foreign liquidity defenses against shocks, emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have limited access to comparable arrangements to help alleviate their foreign exchange liquidity shortages. Only a handful of EMDEs have access to swap lines with advanced-economy central banks.

While advanced economies have established such bilateral swap lines between their central banks to boost their foreign liquidity defenses against shocks, emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have limited access to comparable arrangements to help alleviate their foreign exchange liquidity shortages. Only a handful of EMDEs have access to swap lines with advanced-economy central banks.

EMDEs have instead tended to rely on piling up foreign-exchange reserves as a form of self-insurance. Self-insurance is neither individually nor collectively optimal, and this has prompted discussions about a more robust, multi-layered, global financial safety net.

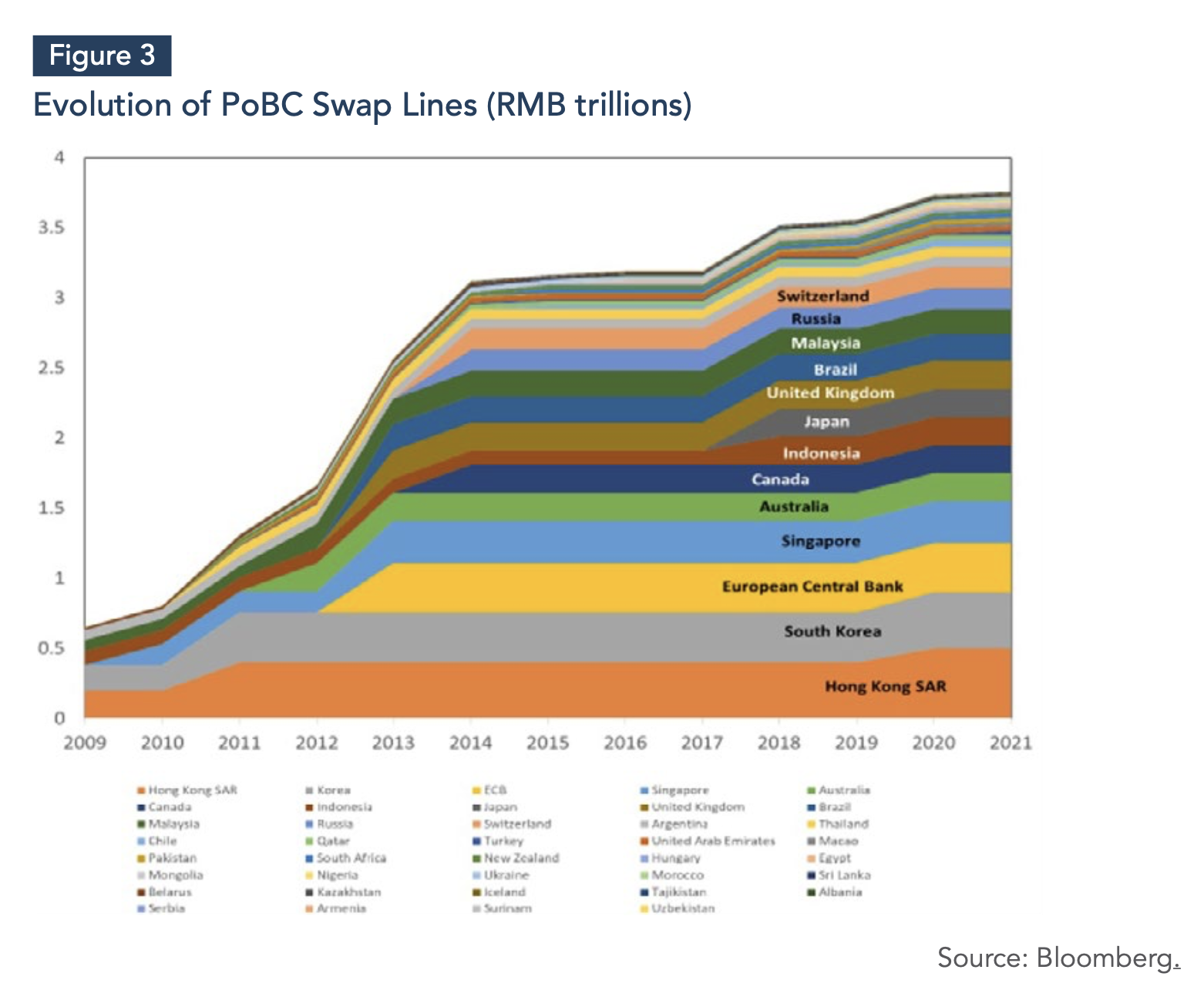

Several EMDE central banks have swap lines with the People’s Bank of China, although the non-convertibility of the renminbi limits the value of these swap lines (Canuto, 2023a) – see Figure 3. The template offered by China aims at facilitating bilateral trade and investment, rather than provision of a safety net. However, Argentina was able to utilize its currency swap line with China in 2023 to overcome difficulties in complying with its debt service obligations with the IMF (Wang and Canuto, 2023).

The Role of the IMF as the Core of the Global Financial Safety Net

The IMF provides the broadest and most general layer of defense against shocks, while—as we have discussed—countries differ very much in their ability to resort to first and second lines of defense. However, the IMF’s lending capacity as a share of global external liabilities has shrunk over time (Figure 2), and the share of borrowed resources has increased (Stanley, 2023).

A series of shocks has become a feature of recent times, constituting a ‘perfect storm’ (Canuto, 2023b): the pandemic, war in Ukraine and Gaza, climate change, and geopolitical uncertainty. A key mission of the IMF is to help members address balance-of-payments needs generated by such shocks.

Uneven access to the Global Financial Safety Net (GFSN) has significant implications for the design of the Fund’s precautionary instruments. The Flexible Credit Line (FCL) was established at the height of Global Financial Crisis (GFC) to help countries address systemic risks such as the GFC and the European sovereign debt crisis. It was assumed that, following the resolution of these systemic risks, the pattern of shocks to the global trading and financial system would revert to that prevailing before GFC. The ultimate objective for the FCL was to signal a country’s ability to access IMF resources without the need for an adjustment program. The Precautionary and Liquidity Line (PLL), meanwhile, is designed to meet the liquidity needs of member countries with sound economic fundamentals, but with some remaining vulnerabilities that require ex-post conditionality and prevent them from using the FCL.

The IMF has established a Short-Term Liquidity Line (SLL) as a liquidity backstop for countries with strong policy frameworks that face potential moderate, short-term liquidity needs. It aims to minimize the risk of shocks evolving into deeper crises and spilling over to other countries. The SLL has not been fully utilized by any country yet. Chile had an SLL from May through September 2022, but reverted to the FCL.

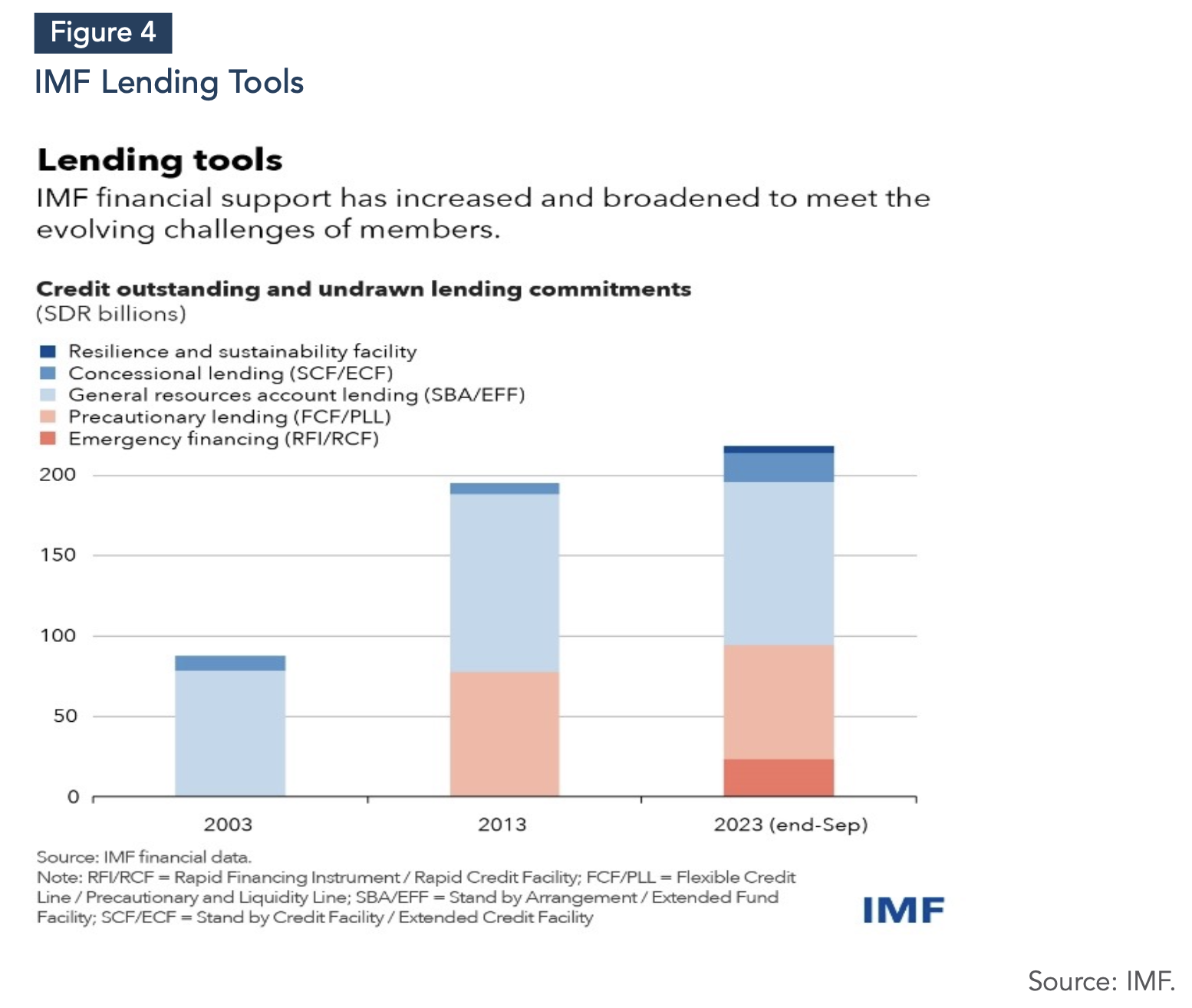

The IMF has deployed $1 trillion in global liquidity and reserves through its lending since the pandemic and the 2021 allocation of $650 billion in Special Drawing Rights (SDRs). Through the Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust, interest-free financing to 56 low-income countries has been provided (Figure 4). As of September 2023, the IMF had lending commitments with 94 countries for about $287 billion, or SDR 218 billion. This included: precautionary facilities for seven emerging market economies for $93 billion; lending commitments to 35 emerging market economies for $134 billion; interest-free lending of $23.5 billion for 45 low-income countries; $30.5 billion of outstanding credit related to emergency financing for 77 countries; and long-term loans of about $6 billion to 11 emerging market economies under the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Facility (RSF). Around 40 more countries have requested or expressed interest in an RSF arrangement.

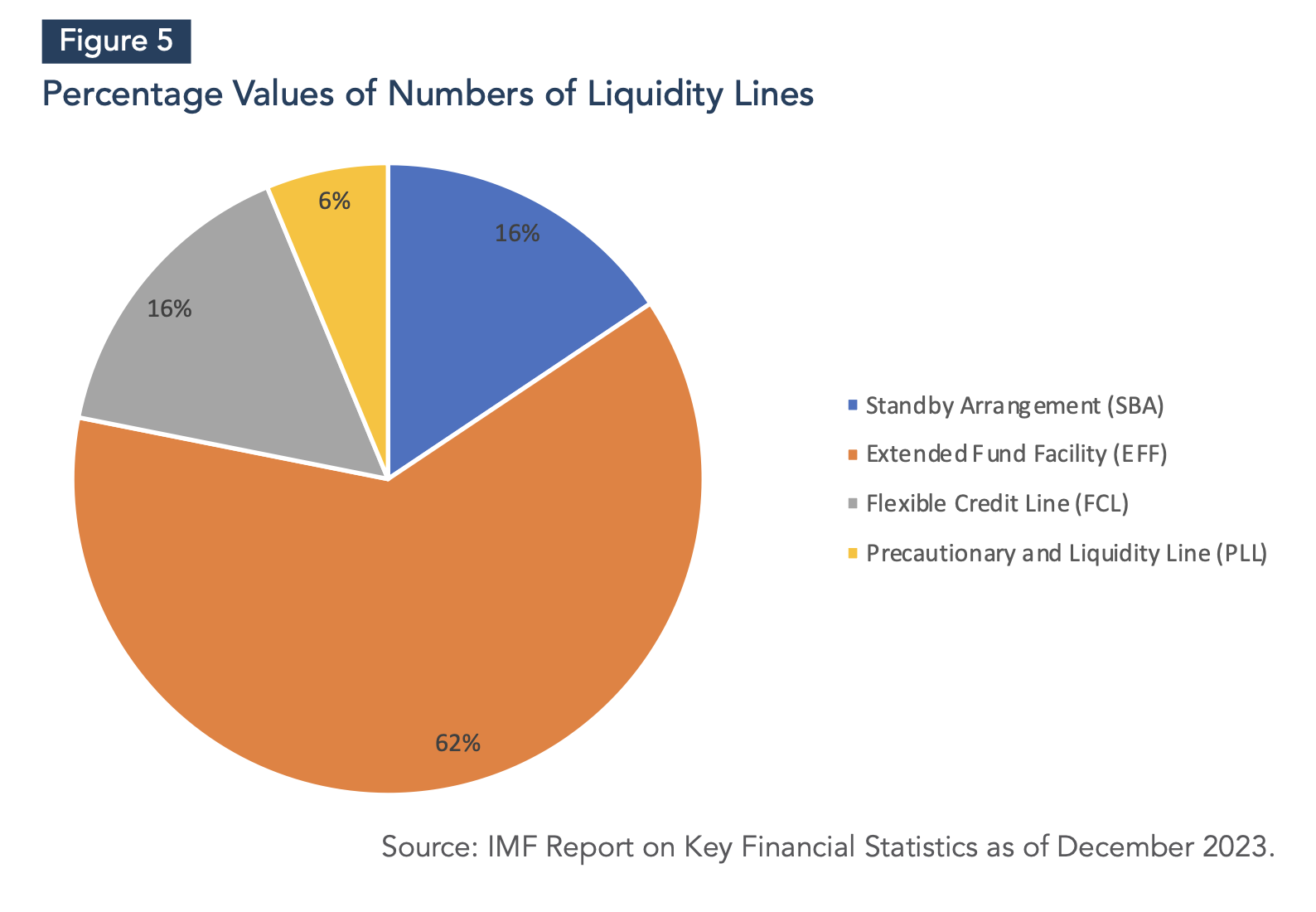

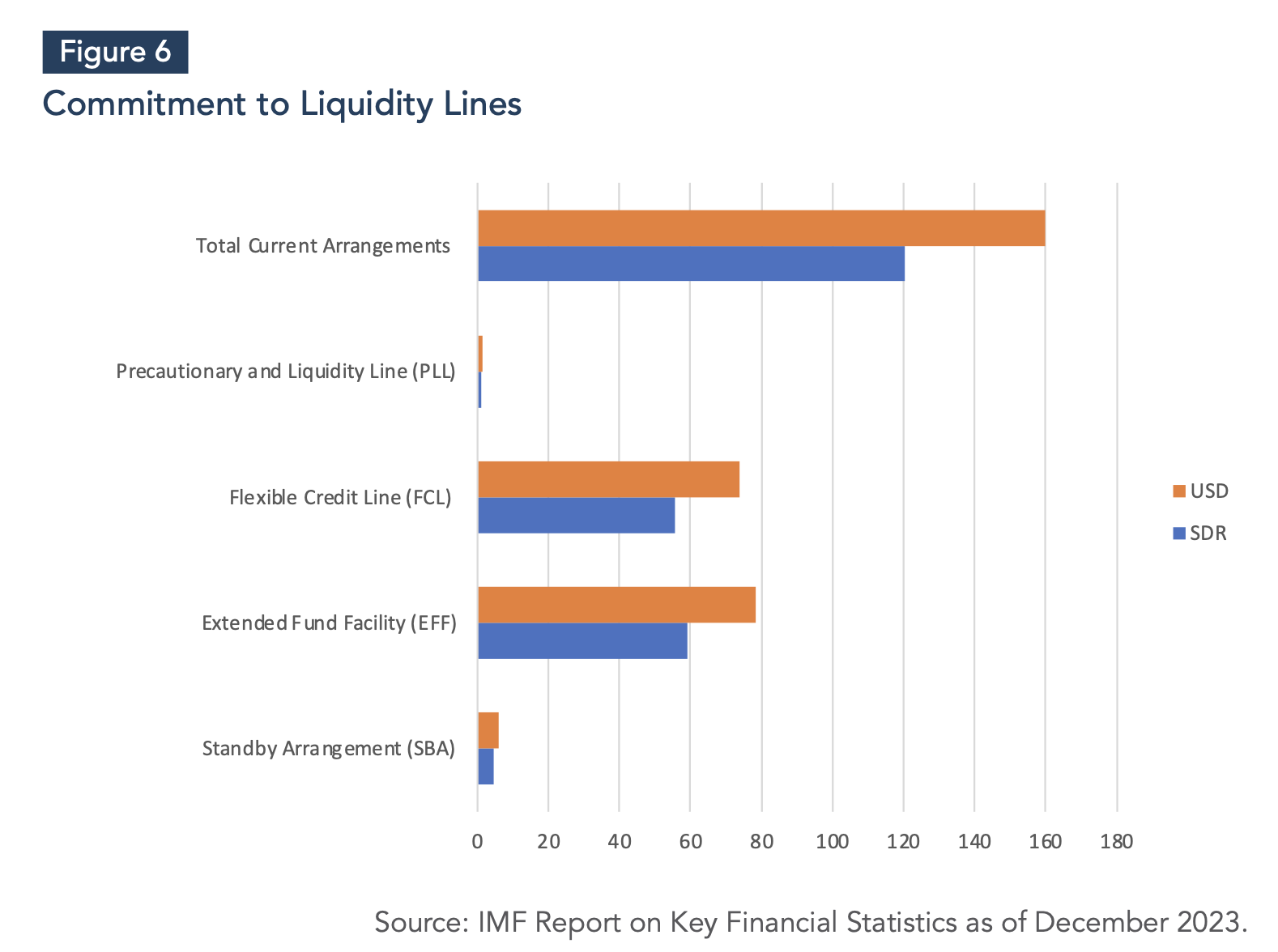

The IMF’s precautionary instruments—the FCL and the PLL—remain underutilized (Figures 5 and 6). At time of writing, only five countries—Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Peru, and most recently Morocco—have access to the FCL.

The IMF’s precautionary instruments—the FCL and the PLL—remain underutilized (Figures 5 and 6). At time of writing, only five countries—Colombia, Mexico, Chile, Peru, and most recently Morocco—have access to the FCL.

Morocco has benefited from a PLL line since 2012 and was the only country to draw on it and use it to fund its liquidity needs during the pandemic in April 2020. Subsequently, Morocco started negotiations with the IMF and concluded an agreement giving it access to the FCL. The first PLL helped Morocco stabilize its domestic T-Bills and foreign-exchange markets, at a time when interest rates were trending upward and the Moroccan currency was under devaluation pressure.

There are currently two PLLs (Jamaica and North Macedonia). This represents a significant increase from two FCLs and one PLL before the pandemic. There is no cap on the funds available under the FCL, while under PLL, member states can access up to 500% of their quota.

The IMF has proposed the following changes under the review of the FCL, SLL and PLL:

The IMF has proposed the following changes under the review of the FCL, SLL and PLL:

– a) An SLL-FCL reform package that allows for combined (FCL and SLL) access of up to 400% of quota without the articulation of exit expectations;

– b) SLL-FCL concurrent use—the concurrent use of FCL and SLL should be permitted. The procedures to make arrangements more easily usable and flexible should be streamlined; for example, the number of board meetings needed for the review of FCL/PLL with Article 1V should be reduced.

The 2011 review of the FCL and PCL found a decline in sovereign spreads, following the announcement of new FCL arrangement (IMF, 2023). The 2014 review of the FCL showed that announcements of a new precautionary arrangement resulted in higher capital inflows and lower sovereign spreads.

The demand for precautionary arrangements will increase as global shocks become multifaceted and global liquidity less easily available. The 2023 review of the FCL showed that announcements of FCL or PLL lead to declines in sovereign spreads. The analysis found that there was a large drop in sovereign spreads for FCL users, ranging from 17 to 24 basis points, in the first seven trading days following the announcements (IMF, 2023).

The analysis found that FCL and PLL arrangements also helped mitigate external financial pressures during the COVID-19 pandemic. After controlling for country-specific effects, time effects, and global and domestic drivers of sovereign spreads, countries with FCL or PLL arrangements during the pandemic experienced smaller increases in spreads, relative to other emerging market economies. Sovereign spreads were about 7% lower in countries with an FCL or PLL arrangement, compared to other EMEs, confirming the important role of precautionary arrangements in cushioning external financing pressures.

Precautionary arrangements can also be cheaper than holding reserves when used on a precautionary basis. They play a complementary role to other layers of the GFSN by offering swift availability of financing when a shock hits. The October 2023 review also called for reforms to the FCL and SLL, allowing the two instruments to better complement each other.

Birdsall et al (2017) provided evidence that the PLL and FCL are among the least costly and most advantageous instruments for liquidity support to countries, and that the economic impact following agreements on an FCL or PLL has been positive in all cases. At the time of their research, their analysis provided evidence that there were at least 18 additional IMF members that would qualify for an FCL, and several more would be eligible for PLL. Since the IMF’s determination criteria for a member state’s eligibility is ambiguous, it serves as a disincentive for new applications. There is also ambiguity about the share of resources the IMF is willing to dedicate to precautionary lending.

Since there is no ex-post conditionality attached to FCL, and very limited conditionality attached to PLL, the two credit lines represent a departure from the IMF’s traditional lending practices. Any major shareholders that may resist to such facilitation should be convinced of its benefits.

The Evolution of Foreign Currency Credit

The global financial safety net must keep up with the evolution of financial intermediation (Carstens, 2021). The rise in U.S. dollar-denominated international debt securities was a strong trend in the last decade. It reflected an increasing role played by non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs) and market-based finance, while U.S. dollar-denominated cross-border bank loans shrank as a share of global GDP (Canuto, 2023c).

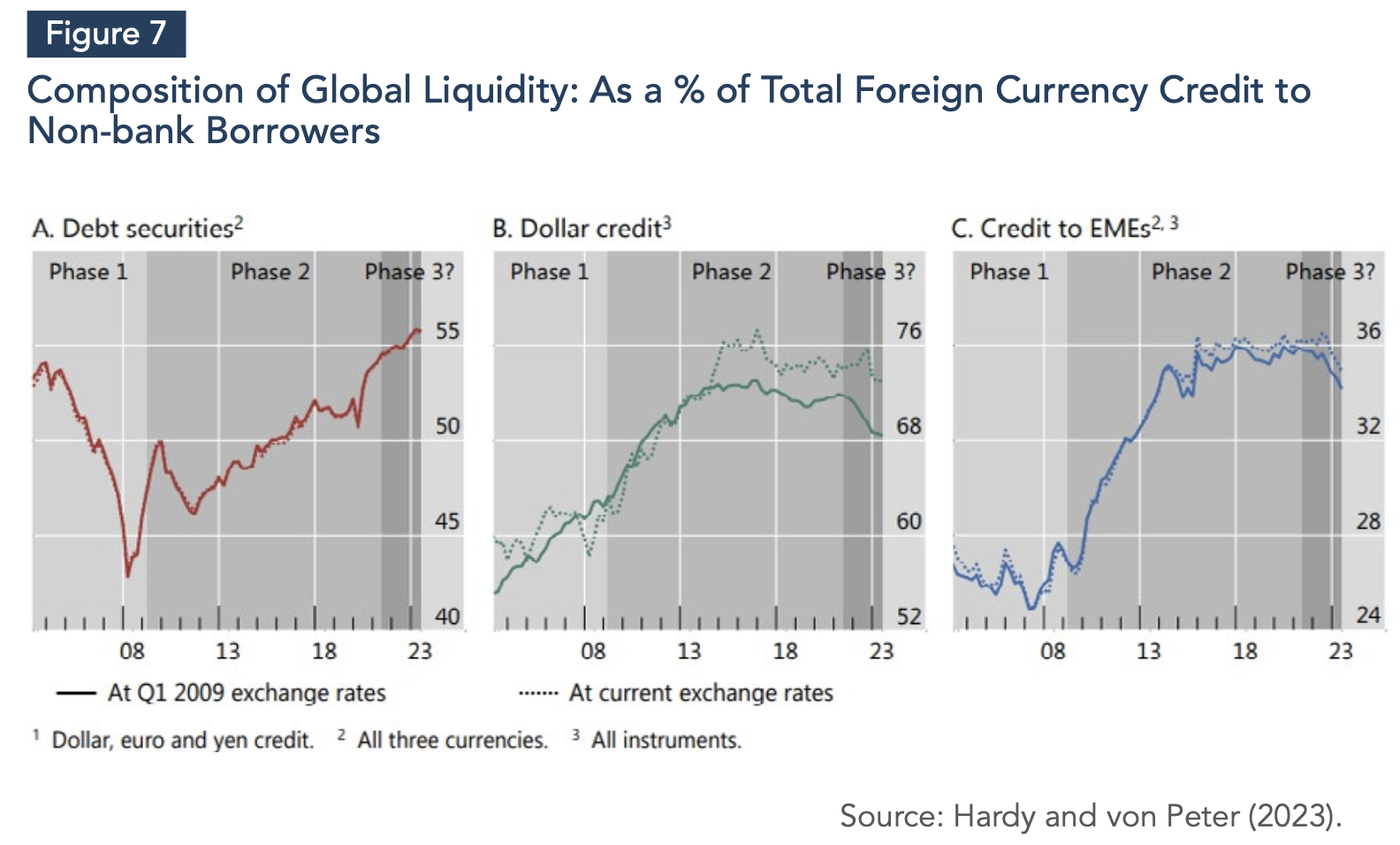

Indeed, global liquidity—the ease of financing in international financial markets—has a key aspect, which is foreign currency credit (FCC), a variable that has undergone distinct phases in recent history (Hardy and von Peters, 2023). The first phase (2003-09) was recorded by Bank for International Settlements global liquidity indicators featuring soaring bank credit, which comprised cross-border credit and credit in foreign currency. This international credit evaporated quickly as the GFC hit, exposing financial vulnerabilities in both advanced and emerging market economies.

Starting in the early 2000s and leading up to the GFC, the first phase of global liquidity saw a large expansion in FCC. The combined stock of foreign-currency credit in dollars, euros, and yen doubled from $5 trillion in Q1 2003 to $10 trillion in Q1 2008 (Figure 7). As a share of world GDP, it rose from 13% to a peak of 17%. This dramatic growth was driven by the rapid expansion in the international activities of banks. A permissive macro-financial and policy environment led to this boom in global liquidity.

The second phase (2009-21) saw a shift towards bond markets and more dollar credits. This phase began in the aftermath of the GFC, and featured a shift to bond-market credit due to tighter regulation of banks. Dollar credit expanded the most, in particular to borrowers in emerging market economies.

The defining feature of the second phase of global liquidity was the shift towards bond markets. The share of foreign-currency credit in the form of bonds rose from a trough of 43% in Q1 2008, to 55% by end-Q2 2021 (Figure 7-A). The dollar, already the dominant currency, saw a further rise in its share in global credit markets (Figure 7-B). Credit to emerging market borrowers took center stage, with their share in FCC rising from 26% in Q2 2009 to 36% by end-2015 (Figure 7-C).

Hardy and von Peter (2023) suggested a third phase of that evolution in global liquidity may be underway. FCC has begun to contract in aggregate. This credit as a share of global GDP fell from 20% at the end-Q2 2021 to 17% at end-Q2 2023.

Hardy and von Peter (2023) suggested a third phase of that evolution in global liquidity may be underway. FCC has begun to contract in aggregate. This credit as a share of global GDP fell from 20% at the end-Q2 2021 to 17% at end-Q2 2023.

The growth of credit from bond markets slowed to a standstill from mid-2021 onward, but its share kept rising because bank lending declined. While the drop in dollar lending by emerging-market banks was particularly sharp, banks of various nationalities drove the decline in lending.

Dollar-denominated credit witnessed a steeper contraction, matching the tighter stance of U.S. monetary policy compared with that of the euro area and Japan. In Q3 2021, the year- on-year growth in dollar credit was 6%, falling to minus 4% at the end of 2022. However, euro credit growth slowed, and yen growth accelerated over the same period. Evaluated at constant exchange rates, the dollar shares of foreign currency credit declined from 72% in mid-2021 to 68% by mid-2023.

Credit to emerging market borrowers declined even more steeply than overall credit. At the end of Q2 2023, euro credit to emerging market borrowers shrank by 2% year-on-year, even as euro credit continued to expand. By mid-2023, dollar credit—the predominant foreign funding currency for most emerging market economies—shrank by 5% year-on- year.

Geopolitical uncertainty and geoeconomic fragmentation could further tighten credit conditions (Canuto, 2023b, 2023d). Financial vulnerabilities built up during the second phase, particularly for the EMDEs that are heavily dependent on foreign currency debt, could be exposed by a sustained tightening of credit conditions.

Country Case Illustrations From Mexico and Morocco

For Mexico, FCL serves as an important buffer. On November 15, 2023, a successor two-year arrangement for Mexico under the FCL was approved. Mexico was the first IMF member to sign an FCL when it was introduced in 2009. Even though so far FCL has been treated as precautionary, it has provided Mexico with a substantial buffer. FCL does not involve any post-approval conditionality, implying that the country can request disbursement anytime once the credit line is approved.

FCL, together with international reserves and swap lines with the U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve, has helped to anchor market confidence in Mexico’s macroeconomic policies. The first line of defense for Mexico includes floating exchange rates and reserves that have served it well. FCL provides an additional external buffer against risks and has contributed to stronger market confidence.

One cannot predict when liquidity shortages happen, but when they do, global capital pipelines freeze up, creating a short-term liquidity problem. Mexico has access to international capital markets with a sovereign rating from Moody’s at Baa2 in 2022, S&P at BBB in 2022, and Fitch at BBB- in 2023, meaning it retains investment grade status, according to all three agencies.

In 2022, gross international reserves stood at $202 billion, which exceeds any standard metric of reserve sufficiency. At the end of 2021, the U.S. Federal Reserve’s temporary COVID-19-related swap lines expired. But Mexico retains the swap line of $3 billion with the Federal Reserve that is associated with the North American Framework Agreement, and a $9 billion swap line with the U.S. Treasury. Mexico also has access to SDR 8.5 billions, as of 2023.

For Morocco, meanwhile, although the country has proved resilient in the last decade in the face of cumulative shocks, and has succeeded in maintaining macroeconomic stability, the global economic and geopolitical landscape can alter swiftly and stress even further the domestic economic situation. There is a growing prominence of ‘geo-economics’ and the accompanying role of hard and soft infrastructure. Much of the infrastructure development over the past years has been directed at reinforcing Morocco’s strong orientation towards Europe and European markets. There has also been an increasing thrust in the country to diversify its set of partners and expand it further. Particularly in focus have been sub- Saharan Africa, the Gulf Countries, and the United States.

Morocco is caught in a dependent economic partnership with Europe making it vulnerable to economic shocks in Europe. It could be affected by economic fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine through lower external demand (especially from the euro area). It is also subject to significant downside risks, including geopolitical risks and volatile global financial conditions and commodity prices, particularly energy prices.

The EU neighborhood policy envisions a strong commitment to provision of assistance to North Africa, but also individualized approaches towards Egypt, Tunisia, and Morocco, including through free trade with southern Mediterranean partners and large-scale investment in regional infrastructure projects.

Morocco’s current account deficit in 2023 corresponded to 1.6% of GDP, according to central bank estimates, and is currently projected to deteriorate to 3.1% of GDP by 2027.

The trade deficit also increased to 16.5% of GDP in 2022. FDI inflows have helped fund the external financing needs. Morocco’s international reserves in U.S. dollars have declined, reflecting the depreciation of the euro against the dollar (60% of Morocco’s reserves are in euros).

It remains important to preserve foreign-exchange reserves so that they can provide a buffer against uncertainty and Morocco’s pegged exchange-rate regime with horizontal bands (+/- 5%). Even though there has been an increase in lending from bilateral and multilateral lenders, the authorities need to diversify their financing sources and access international financial markets. Morocco accessed the international financial market in March 2023, one of the few countries in Middle East and North Africa to do it in the current turbulent context.

Bank Al-Maghrib (BAM) should also move forward to the final stages of transition to an inflation-targeting framework, and allow the dirham to float freely, which would strengthen Morocco’s resilience against future shocks. Morocco’s central bank envisions achieving this reform by 2027, according to its 2024-2027 strategic plan.

In line with the recommendations made by the IMF in its latest Financial Sector Assessment Program (FSAP) of Morocco, progress has been made by increasing supervisory capacity and improving BAM’s stress testing and macroprudential policy framework with technical assistance provided by the IMF. The oversight of Moroccan banks expanding into Africa has intensified, in close collaboration with supervisory agencies in host countries. From February 2020 to the end of 2020, there was a need to directly support firms under financing constraints, and to respond to growing demand for liquidity in the banking system (both in domestic and foreign currency), as well as a call for an expansion of the liquidity provision to the banking sector. This can be achieved through more refinancing operations by BAM.

The PLL arrangement provided useful insurance against external shocks while bolstering investor confidence. PLL is treated as precautionary and is only drawn on in the event of unforeseen exogenous shocks. Since 2012, Morocco had four successive PLL arrangements. In 2012, a two-year PLL arrangement amounting to SDR 4.12 billion was approved. This was followed by successive two-year PLL arrangements: one with access to SDR 3.2351 billion approved in 2015, and another with access to SDR 2.504 billion, approved in 2016. In 2018, a fourth two-year PLL arrangement was approved, amounting to SDR 2.15 billion. During the COVID-19 pandemic, in April 2020, Moroccan authorities purchased all available resources under the PLL arrangement (which is around 3% of GDP), in order to maintain official reserves. The authorities made an early repurchase of SDR 650 million after the country issued U.S. dollar-denominated bonds. As a result, SDR 1.4998 billion remains outstanding as of January 2024.

In April 2023, the IMF approved a two-year arrangement for Morocco under the FCL designed for crisis prevention, worth about $5.0 billion, equivalent to SDR 3.7262 billion. Morocco’s strong institutional policy frameworks justified the transition to an FCL arrangement, and this has taken place. The FCL will help in accelerating the implementation of the structural reform agenda, enhance Morocco’s external buffers and provide the country with further insurance against risk.

Morocco’s sovereign rating was Ba1 in 2022 according to Moody’s, BB+ since 2021 according to S&P, and BB+ in 2023, according to Fitch—non-investment grade levels. However, in March 2023, Morocco was able to issue two dollar-denominated bonds, with five and ten-year maturities, each for $1.25 billion with favorable spreads, reflecting high demand from international investors. Morocco only has access to SDR 857.2 million.

However, the main point is that, like Mexico, Morocco’s lines of defense against shocks have been enhanced by the transition to an FCL.

The Bottom Line: The ‘Global’ Part of the GFSN Needs Boosting

There remain weaknesses in the global financial safety net for emerging markets and developing economies, particularly for those unable to accumulate large international reserves. These will remain subject to capital-flow and exchange-rate volatility, while the reliance on FCC will continue to be a source of vulnerability. There is therefore an overall need to strengthen the global financial safety net, by strengthening IMF liquidity provision and widening the financial safety net. Addressing capital-market volatility should also be pursued (UN, 2023).

To strengthen liquidity provision and widen the financial safety net, UN (2023) suggested several reforms, among which:

– Boost the function and purpose of SDRs by allocating them based on need, instead of quota multiples.

– Make IMF lending more flexible, with fewer conditionalities and access limits, and the removal of surcharges. Quotas and resource contributions should be delinked from lending. This will bolster the capacity to protect against future crises, supporting members with smaller financial buffers, who most need such buffers.

– Establish a multilateral currency-swap facility, providing liquidity at low cost.

A revamped global financial safety net should include additional resources for the IMF as well as reforms. The increase in the IMF’s quota-based resources agreed in 2023 has been a step in that direction, but as noted above, there is still some way to go to reestablish the IMF as the truly global layer of external financial protection.

The IMF’s governance structure must also enhance its legitimacy, improving its basic quota formula of constitution. Aligning the distribution of quotas with the current characteristics of the world economy is fundamental (Coulibaly and Prasad, 2023).

Finally, the IMF should simplify the modalities for augmenting access under FCL, as a greater number of emerging economies with access to precautionary lending would make the system more stable. As stated by Brazil’s Minister of Finance, Fernando Haddad, at the International Monetary and Financial Committee meeting in October 2023, in Marrakech:

“Precautionary arrangements are key instruments to foster global prosperity and financial stability. (…) Precautionary facilities help align incentives towards good policies and reinforce solid institutions. The changes that were recently adopted by the IMF Executive Board constitute a very important step in the right direction, by making the use of these facilities more attractive, without lowering the qualification criteria, so as to not weaken the signal. In particular, the concurrent use of the FCL and the SLL and the non-presumption of exit from low-access FCL will help make these facilities an integral feature of a more effective global financial safety net, with a stronger focus on prevention rather than remediation.”

The global financial safety net needs to be reinforced, especially in terms of its capacity to support emerging market and developing economies.

REFERENCES

Birdsall, N.; Rojas-Suarez, L., and Diofasi, A. (2017). Expanding Global Liquidity Insurance through Precautionary Lending: What the IMF can do. CGD – Center for Global Development.

Canuto, O., and Cavallari M. (2017). The Mist of Central Bank Balance Sheets, Policy Brief PB-17/07, February.

Canuto, O. (2021). Helicopter Reserves to the Rescue, Policy Center for the New South, September 1.

Canuto, O. (2023a). Rising Use of Local Currencies in Cross-Border Payments, Policy Center for the New South, August 29.

Canuto, O. (2023b). Resilience and Realignment of Global Trade, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB – 44/23, November.

Canuto, O. (2023c). “Capital flows and emerging market economies since the global financial crisis”, In Gevorkyan, A.V. (ed.), Foreign Exchange Constraint and Developing Economies, Edward Elgar.

Canuto, O. (2023d). Growth Implications of a Fractured Trading System, Policy Center for the New South, September 21.

Carstens, A. (2021). Rethinking the global financial safety net, Speech at the Sixth High-Level Regional Financing Arrangements (RFA) Dialogue, October 12.

Coulibaly, B., and Prasad, E. (2021). Global liquidity insurance: a proposal to strengthen the financial safety net, The Banker, October 15.

IMF – International Monetary Fund (2023). Review of the Flexible Credit Line, The Short Term Liquidity Line and the Precautionary and Liquidity Line, and Proposals for Reform, October.

Hardy, B. and von Peter, G. (2023). Global liquidity: a new phase, BIS Quarterly Review, December.

Iancu, A.; Kim, S.; and Miksjuk, A. (2021). Global Financial Safety Net—A Lifeline for an Uncertain World, IMF Blog – Chart of the Week, November 30.Saraiva, B., and Canuto, O. (2009). Vulnerability, Exchange Rate and International Reserves: Whither Brazil? Roubini EconoMonitor, September 21.

Saraiva, B., and Canuto, O. (2009). Vulnerability, Exchange Rate and International Reserves: Whither Brazil? Roubini Economonitor.

Stanley, A. (2023). Global Financial Safety Net, IMF – Finance and Development, December.

UN – United Nations (2023). Our Common Agenda Policy Brief 6: Reforms to the International Financial Architecture, May.

Wang, X., and Canuto, O. (2023). The Dollar-Renminbi Tango: The Impacts of Argentina’s Potential Dollarization on its Relations with China, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB – 39/23, October

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a former vice president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund, and a former vice president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at the University of São Paulo and the University of Campinas, Brazil. Currently, he is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development.

Amshika Amar is an Associate Fellow, Centre for Social and Economic Progress. Previously, she has worked with the World Bank Group in various global practices.

This Post Has 5 Comments

Your insights are truly valuable.

you are in reality a good webmaster The website loading velocity is amazing It sort of feels that youre doing any distinctive trick Also The contents are masterwork you have done a fantastic job in this topic

Wow, wonderful blog format! How lengthy have you been blogging for?

you made blogging look easy. The full glance of your website is magnificent, let alone the

content! You can see similar: najlepszy sklep and here sklep

You are a good author. Great article. It was a real pleasure to read.

You are a good author. Great article. It was a real pleasure to read your article.

Comments are closed.