Policy Center for the New South – Policy Paper PP – 17/22

Also: Seeking Alpha; TheStreet.com

1 Introduction

Inflation as a global phenomenon has triggered the simultaneous tightening of monetary and fiscal policies internationally. Consequently, global economic growth projections for 2022 and 2023 have been revised downward. As inflation rates will come down only gradually, given the price stickiness of their core components, the world faces a situation of ‘stagflation’—a combination of significant inflation and low or negative gross domestic product (GDP) growth.

In this briefing, we assess how this global stagflation episode might evolve: towards a soft landing, a sharp downturn, or a deep recession (borrowing those scenarios from a September 2022 World Bank report; see Guénette et al, 2022). As the evolution of the situation will depend on how fast inflation drops in response to economic deceleration, we frame our response in terms of assessing the shifts in major economies’ Phillips curves, which illustrate the relationship between inflation and unemployment.

Phillips curve shifts will also reflect the cross-border spillovers of country-specific policy choices. Furthermore, the sudden abrupt deterioration of financial conditions may cause additional Phillips curve movement.

Section 2 considers that a global recession—global GDP rising more slowly than the population, and thereby global per-capita GDP shrinking—is a strong possibility. The combination of economic slowdown and inflation will be different in different countries but will be a common feature.

Section 3 revisits the rationale behind Phillips Curve, i.e., the dilemma between inflation and unemployment faced by policymakers. We compare the underpinnings of the inflation/unemployment trade-off as they were in the 1970-1980s, during the ‘great moderation’, and now after the perfect storm provoked by the pandemic and the war in Ukraine. We suggest that ultimately the prognosis for the global economy will depend on the shapes of country-specific Phillips curves after recent drifts, while also being affected by the cross-country spillovers of local policy decisions.

To illustrate cross-country interactions, Section 4 summarizes recent challenges arising from the strong appreciation of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies, particularly those of other major economies. This may reinforce the contractionary pressures on the global economy. In emerging-market and developing countries (EMDEs), although exchange-rate depreciation has not been as intense as in non-U.S. advanced economies, vulnerabilities associated with dollar-denominated liabilities could intensify problems.

Finally, Section 5 sets out three scenarios for the global economy in 2022-2024. We sketch out what a soft landing, a sharp downturn or a deep recession might look like.

2 Global Monetary Policy Tightening Underway

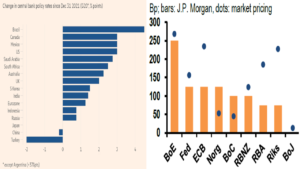

Recently, interest rate rises have been widespread in the global economy. The left side of Figure 1 depicts basic interest rate hikes since 2021, while its right side shows market estimates of rate hikes in advanced economies up to the second quarter of 2023.

Figure 1: Global Monetary Policy Tightening

Note: Bp – basis points. Sources: Wolf (2022) (left side) and J.P. Morgan Global Economics (right side).

On September 21, 2022, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) raised the target for the federal funds rate by 75 basis points, bringing it into the 3% to 3.25% range, in addition to signaling a noticeably higher level at the end of the current hiking cycle.

The Fed has maintained its ‘forward guidance’ that further rate hikes will be appropriate. It noted that while national spending and production have declined, the increase in employment has been robust. There is a clear presumption that risks of wage-price spirals will not disappear before the labor market tightness gives way to looseness and wage moderation.

Individual projections by the members of the Fed’s Open Market Committee (FOMC)[1], changed significantly compared to those issued in June 2022. The September median federal-funds interest rate projections pointed to a rate of 4.4% at the end of 2022, with only two remaining FOMC meetings. It appears that committee members expect a 75 basis-points increase in November, and another 50 basis-points increase in December, up from the previously expected 50 and 25 basis points, respectively.

Rates are expected to rise a little further in early 2023, with a projected peak of 4.6% according to the median of committee members’ opinions, remaining there until 2024. Fed chairman Jerome Powell said after the September meeting that rates will have to remain restrictive enough to keep the U.S. economy running below its potential for a while, something that would be necessary to reduce inflation.

This appeared in downward revisions to forecasts for real GDP growth: 0.2% year-on-year in Q4 2022, followed by 1.2% and 1.7% in 2023 and 2024, respectively. Growth over the next two years will be below the estimated potential level of 1.8%. The Fed has revised its inflation forecast upward through 2024, with inflation not reaching its target until 2025.

The Fed also revised its forecast for the unemployment rate, predicting it will rise from 3.7% now to 4.4% by the end of 2023. Historically, a rise in the unemployment rate of this magnitude over a year has always been followed by a recession.

In July 2022, we called into question whether two consecutive quarterly negative GDP numbers were enough to state that the U.S. economy was already in recession (Canuto, 2022a). In addition to a discrepancy between negative GDP and positive gross domestic income (GDI) numbers in the second quarter, the performance of the labor market did not point to strong deceleration already in course, even if the job market responds to the real economy side with a time lag. The slowdown in the labor market is undoubtedly part of the objectives currently pursued by the monetary authorities and reflects the priority given to lowering inflation.

There is a general rise in interest rates, as seen in Figure 1 (though with some exceptions: China, Japan, Turkey). In the week of the Fed’s September meeting, the central banks of Switzerland, Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Hong Kong (China), the United Kingdom, Indonesia, the Philippines, and South Africa hiked rates, as the European Central Bank and the Bank of Canada had done in the previous week. In Brazil, there was no increase, not least because a strong cycle of interest rate hikes has already occurred since last year.

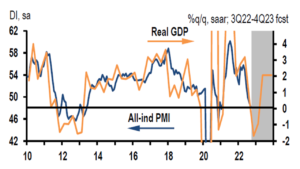

In July 2022, the European Central Bank (ECB) hiked interest rates for the first time in 11 years. On September 8, it agreed the highest increase to date, by 75 basis points. After being at zero or in negative territory for more than a decade, the European Union now has a rate of 0.75%. Despite the clear signs of a slowdown in economic activity, the ECB’s interest rate should continue to rise. In the euro area, industrial production dropped significantly in July 2022 (Figure 2), as a result of the energy price shock, while headline inflation projected for September was already close to 10% per year.

Figure 2: Euro-Area All-Industry PMI and Real GDP

Source: J.P. Morgan Global Economics

The phenomenon of higher inflation is global in scope, prompting central banks around the world to push their restrictive buttons. With some exceptions, as in the case of China, Russia, Japan, and Turkey (Figure 1, left side).

There is an intrinsic challenge to the globalized economy. Each central bank looks to its own country, deciding monetary policies according to what it thinks is necessary regarding the local dilemma between unemployment and inflation. But in such an interdependent economy, the repercussions of any major country’s decisions go far beyond its borders and back. The probability of feedback from restrictive monetary policies is greater when they are all responding to a common inflationary problem.

For various reasons, China’s economic growth has been slowing this year (Canuto, 2022b). The Eurozone also appears to be sliding towards an economic contraction, as noted above. The combination of higher energy prices, U.S. dollar appreciation relative to the euro, China’s growth deceleration, and risks of a second eurozone debt crisis as interest rates and risk premium on Italian bonds go up, leads one to strongly expect recession in Europe. Taking additionally into account the slowdown in the United States, a “global recession” is likely to occur, that is, a fall in global GDP per capita.

A September report by the World Bank – Guénette et al (2022) – noted how, despite the global slowdown in growth underway, inflation in many countries has risen to the highest levels in decades. Consequently, the global economy is experiencing a period of international synchronicity in the tightening of monetary and fiscal policies, like the one that preceded the global recession of 1982, while global economic growth decelerates.

A key variable in this regard will be the evolution of the inflation rate, requiring – or not – intensifying the tightening. With inflation hovering around the multi-decade highs in Europe and the US and activity weakening, the course for monetary policy faces a challenge. Monetary policy commands strong credibility and inflation expectations remain stable in Europe and the US, but one concern is that high inflation itself raises the risk for second-round effects on wages. Second round effects on wage levels have been observed in the recent past but not sustained increases in wage and price inflation.

It remains to be seen to what extent, in the coming months, price feedbacks and the inflationary spiral in the largest economies will yield to fiscal and monetary tightening without requiring even stronger doses. In any case, the downward revision of global growth projections in 2022 and 2023 has already been remarkable.

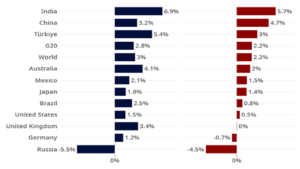

The September 2022 OECD Economic Outlook revised downward its projections of GDP growth in 2022 and 2023 (Figure 3). Global growth is projected to remain subdued in the second half of 2022, before slowing further in 2023 to an annual rate of just 2.2%. Compared to the OECD forecasts from December 2021, before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, global GDP is now projected to be at least $2.8 trillion lower in 2023.

Figure 3: Real GDP Growth Projections for 2022 and 2023 (Selected countries, year-over-year, %)

Source: OECD (2022).

3 Whither the Phillips Curve?

The Phillips curve represents the inverse relationship between inflation rates and the unemployment rate and/or the degree to which a country’s potential GDP is effectively being produced. Inflationary pressures increase as unemployment declines and/or the heating up of economic activity starts to conflict with its capacity, and vice versa. The curve is named after the British economist A.W. Phillips, whose 1958 paper examined unemployment and wage growth in the United Kingdom between 1861 and 1957.

The relevance of the Phillips curve for macroeconomic analysis and monetary policy decisions is immediate, as interest rate decisions by central banks depend on the level of aggregate demand and, therefore, on the extent to which potential GDP will be under- or over-utilized. The Phillips curve expresses the ‘inflation-unemployment dilemma’.

In principle, at each moment in time, there would be a level or range of interest rates at which demand pressures would not be excessive or would be insufficient in relation to potential GDP, not by chance called the ‘neutral’ interest rate, since inflation levels and unemployment would tend to remain stable. Consistently, there is the idea that there is a certain rate of unemployment at which inflation remains stable – the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU).

The relationship between unemployment and inflation expressed in the Phillips curve does not necessarily remain stable. In addition to possible supply-side shocks altering the relationship, there are also endogenous changes when the economy spends some time operating far above – or below – the neutral level.

In situations of overheating and rising inflation, the expectations of economic agents in relation to this can lead them to react in ways that end up establishing vicious circles of inflationary feedback. What’s more, once that happens, expectations and behavioral feedback will only be reversed if the economy spends some time below its potential, during which the inertia of inflation will keep it going for some time.

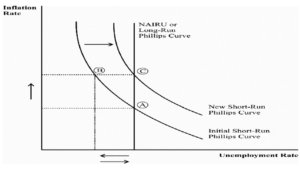

This is illustrated by the shift of the initial short-run Phillips curve toward a new short-run Phillips curve (Figure 4), after some time spent at point B, rather than point A. Stability can then only be reached with the unemployment rate moving back to NAIRU (point C in Figure 4). Any return to point A will likely demand a period of unemployment rates above NAIRU, coupled with an unwinding of inflation expectations and of wage-price spirals.

Figure 4: The Phillips Curve

Source: Dritsaki and Dritsaki (2013).

The so-called ‘stagflation’ (significant inflation, high unemployment, and zero or low economic growth) observed in the 1970s and 1980s in the United States corresponded to being in a zone to the right of point C in Figure 4. The Phillips curve had shifted upwards, and inflation only declined after a period of high unemployment.

Conversely, the following decades saw the period of ‘great moderation’, the name given to the period of low macroeconomic volatility experienced in the United States from the mid-1980s until the 2007-2008 financial crisis. The Phillips curve had shifted down.

After the ‘great recession’ that followed the global financial crisis, the shift seemed to have been confirmed. The U.S. economy took a while to recover but ended up going through a long and steady expansion for more than a decade, at rates below historical averages, but corresponding to a time record without recessions. Unemployment remained low, with a rate lower than the lowest points of the previous 50 years, dropping to 3.5%.

Meanwhile, inflation remained below the Federal Reserve’s 2% target, averaging 1.7% throughout the expansion. The looseness of monetary policy—including quantitative easing, or the Fed buying government bonds and mortgages—did not affect inflation (Canuto, 2022d).

Two main factors explain this ‘flattening’ of the Phillips curve. The first was the anchoring of inflation expectations at low levels. The second was the possibilities opened by the globalized economy: instead of upward pressures on the domestic prices of products that might be in short supply, imports could act as absorbers of demand. In the absence of generalized overheating, globalization could function as a buffer against inflation in individual countries.

Then came the rise in inflation with the supply shocks accompanying the pandemic, the invasion of Ukraine, and the “perfect storm” (Canuto, 2022c). From being considered a temporary phenomenon, accelerated inflation came to be recognized as something that is not automatically reversible.

This is not least because it also reflects the size of fiscal and monetary stimulus in advanced economies, with the sharp channeling of demand for goods—in place of services—creating bottlenecks in supply chains and conflicting with supply capacities. In addition, the workforce has contracted, reducing possible employment levels.

The Phillips curve has shifted. As Gita Gopinath, the IMF’s first deputy managing director, outlined in a presentation at the Federal Reserve’s August 2022 Jackson Hole Economic Symposium, less than a quarter of a percentage point of the rise in inflation can be attributed to unemployment falling below the ‘natural’ rate estimate, or NAIRU (Gopinah, 2022). In any case, there is now a simultaneous development internationally in the tightening of monetary and fiscal policies, making a global recession likely, as we have discussed.

And now? Where will the Phillips curve go? Will the relationship return to how it was before the pandemic?

According to the Institute of International Finance (Brooks et al, 2022), the effect of the pandemic as a source of shocks on supply chains seems to have ended, given the stage of normalization of delivery times and the reduction of its upward pressure on inflation. On the supply side, however, there are still the impacts of the war in Ukraine on global inflation, especially in Europe.

Furthermore, the post-pandemic job supply will remain difficult to predict for some time. There is also the risk that “relative deglobalization” of value chains undermines the balancing of supply and demand via foreign trade, rather than domestic prices (Canuto, 2022e; Canuto et al, 2022).

And on the aggregate demand side? Will the long-term low interest rates that prevailed in the recent past return, or will the ‘perfect storm’ bring structural changes?

Gopinath suggested that while demographics, income inequality, and a preference for safe assets will continue to keep rates low, higher debt post-pandemic and inflationary shocks accompanying the energy transition (Canuto, 2021c) will work in the opposite direction. In turn, it is difficult to predict where labor supply and productivity will go.

The Philips curve will keep moving. Meanwhile, it is also necessary to verify whether the monetary adjustment programs underway will be effective in keeping inflationary targets as anchors for expectations. This may make the difference in terms of which growth deceleration scenario prevails.

4 U.S. Dollar Appreciation May Be Contractionary

The recent strong appreciation of the U.S. dollar relative to other currencies, particularly of other major economies, may reinforce the contractionary pressure on the global economy. In emerging market and developing countries (EMDEs), although exchange-rate depreciation has not been as intense as for non-U.S. advanced economies, vulnerabilities associated with dollar-denominated liabilities may lead to intensified problems.

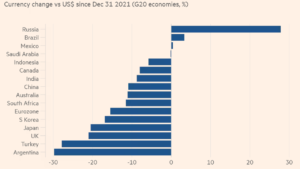

Take the U.S. Dollar Index (DXY), a measure of the value of the dollar against six other world currencies[2]. On September 28, the DXY was at its highest level since May 2002. Compared to the beginning of 2022, the dollar was up 18% against the euro, and 26% against both the Japanese yen and British pound. Figure 5 shows how 20 G20 currencies have so far in 2022 evolved relative to the U.S. dollar.

Figure 5: G20 Currencies Relative to the U.S. Dollar in 2022

Source: Wolf (2022).

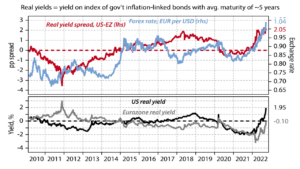

A key additional driver of the U.S. dollar appreciation has been the higher yield in real terms of U.S. assets relative to others. Figure 6 shows the differential in real yields between the U.S. and the euro area, as measured by yields on five-year inflation-indexed government bonds, pairing it with the euro-dollar depreciation. It reflects the more rapid interest rate moves in the U.S., followed by market expectations about the Fed’s anti-inflation drive, compared to others.

Figure 6: U.S. and Euro Area: Real Yields and Exchange Rates

Source: Denyer, W. (2022). The Key Drivers for Currencies, Gavekal Research, September 28 (www.gavekal.com).

According to W. Denyer, a similar picture may be built more broadly for the comparison of risk-adjusted rates of return for other fixed-income assets. Given the heights already attained by the dollar, further bouts of dollar appreciation might happen only if the other central banks continue to lag in setting interest rates and/or the pace of adjustment by the Fed accelerates even further. There are also always, of course, one-off events, such as an intense depreciation of the British pound caused by a proposal for unfunded tax cuts, that in early October was partly reversed.

Some countries have tried direct interventions in exchange rates instead of—or as a complement to—lifting domestic interest rates. Japan has opted to sell U.S. Treasury bond reserves to try to counteract the yen’s exchange rate devaluation against the dollar. Switzerland also said to be considering selling foreign currency to support the Swiss franc, as well as raising interest rates between meetings of its central bank.

The period after the 2008-2009 global financial crisis saw ‘currency wars’, when countries accused each other of exporting their unemployment problems through significant reductions in domestic interest rates and currency devaluation. A ‘reverse currency war’ may now be emerging, as the appreciation of the U.S. dollar exports inflation to others. Clearly, in the absence of some sort of new Plaza Accord[3], individual country efforts to evade interest rate adjustments via direct interventions in exchange markets will have limited effect, if the underlying factors leading to capital flows are not altered.

In any case, besides hurting U.S. multinational companies’ profits from abroad, as well as emerging markets’ dollar-denominated foreign liabilities (Canuto, 2020), one way or another the U.S. dollar appreciation may lead to inflationary shocks in other countries and, thereby, even tighter monetary policies. Feedback loops of restrictive policies may be sparked by drastic and sudden U.S. dollar appreciation.

The scenario the global economy will follow will depend on local combinations of inflation stickiness, necessary monetary tightening, and financial vulnerability. Where Phillips curves have moved to will matter.

5 Three Different Near-Term Scenarios

Since the beginning of 2022, a rapid deterioration of growth prospects, coupled with rising inflation and tightening financing conditions, has ignited a debate about the possibility of a global recession—a contraction in global per-capita GDP (Canuto, 2022c).

Consensus forecasts for global growth in 2022 and 2023 have fallen significantly since the beginning of the year. Although these forecasts do not point yet to a global recession in 2022–2023, Guénette et al (2022) call attention to the experience of earlier recessions, highlighting at least two recent features that indicate a high likelihood of a global recession in the near future.

First, every global recession since 1970 was preceded by a significant weakening of global growth in the previous year, as has happened recently. Second, all previous global recessions coincided with sharp slowdowns or outright recessions in several major economies.

Despite the current slowdown in global growth, inflation has risen to multi-decade highs in many countries. To curb the risks from persistently high inflation, given the context of constrained fiscal space, many countries are withdrawing monetary and fiscal support. The global economy is in the middle of one of the most internationally synchronous episodes of monetary and fiscal policy tightening of the past five decades.

These policy actions are understood as necessary to contain inflationary pressures. But, as we have discussed, their mutually compounding effects could lead to greater impacts than intended, both in terms of tightening financial conditions and in accelerating the growth slowdown. While such tightening policy conditions were not seen at the time of the 1975 global recession, they were before the 1982 recession.

Guénette et al (2022) propose three scenarios for the global economy in 2022-2024 as possible near-term growth outcomes. The first baseline scenario follows closely recent consensus forecasts of growth and inflation, as well as market expectations for policy interest rates. One may call it a ‘soft-landing’ scenario.

In such a baseline scenario, global growth is forecast to slow from 2.9% in 2022 to 2.4% in 2023, rising to 3% in 2024. The slowdown in 2023 would lead to growth in per-capita terms approaching that of the downturn episodes of 1998 and 2012. Global trade growth would reflect a broad-based weakening of demand in 2023, before accelerating in 2024.

Growth in advanced economies would slow from 2022 to 2023, before recovering somewhat in 2024. In turn, growth in emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) would accelerate from 2022 to 2024, as global headwinds fade, and the post-pandemic recovery continues.

How about inflation? After peaking at 7.7% in 2022, global headline CPI inflation in the baseline scenario would remain high relative to the inflation target into 2023, at 4.6%. However, the projection for 2024, at 3.2%, is in line with a gradual approach to the target, which is about 2.5% at the global level in GDP-weighted terms (average 2% in the U.S.).

Inflation in EMDEs is projected to decline rapidly from 9.4% in 2022 to 4.5% in 2024, staying above its aggregate target of around 3.5%. The decline in core CPI inflation, which excludes the volatile energy component, would be more sluggish. Given this inflation outlook and the expected path of policy rates, short-term interest rates would remain negative, or near zero, in real terms throughout most of the projection horizon.

However, there is a possibility that the degree of monetary policy tightening currently expected may not be enough to restore low inflation quickly enough to quell inflation fears. The second scenario—sharp downturn—supposes an upward move in inflation expectations, which would lead to additional synchronous monetary policy tightening by major central banks.

Major central banks in advanced economies and EMDEs are then assumed to raise their benchmark policy rates by a cumulative 100 basis points above baseline assumptions over the rest of 2022 and the end of 2023, deciding to sustain this differential through 2024. In this scenario, the global economy would still escape a recession in 2023 but would go through a sharp downturn without restoring low inflation by the end of the next year. While headline inflation would continue its downward trajectory in 2024, it would do it at a slower pace. The decline in core inflation, on the other hand, would be broadly unchanged relative to the baseline scenario, as the upward pressure from higher inflation expectations would counterbalance the muted impact of widening output gaps.

According to model-based projections in Guénette et al (2022), the global economy would still escape a recession in this sharp-downturn scenario, despite undergoing a global downturn (in per-capita terms) on par with that in 2001, and worse than those in 1998 and 2012. Advanced economies overall would not see a contraction of output in 2023, with growth of 0.5%. However, the additional tightening of monetary policy would lead to so-called ‘technical recessions’, i.e., two consecutive quarters of negative quarter-over-quarter growth, in both the United States and the euro area in 2023. Recovery of activity in this scenario would take place in 2024. However, the projected GDP growth rate of 2.7% would be 0.3% below the baseline-scenario rate.

In the third scenario—global recession—the additional increases in policy rates would trigger a sharp re-pricing of risk in global financial markets, resulting in a global recession in 2023. As in some previous experiences, abrupt policy shifts in major economies might cause deep global financial stress, aggravating already heightened macroeconomic vulnerabilities.

Differently from the period of the great moderation, the focus on inflation reduction would constrain the ability of central banks to provide relief to stressed financial markets, beyond some eventual targeted credit easing to alleviate acute liquidity shortages in key funding markets, as lenders of last resort. Fiscal policy is also expected to face similar constraints, preventing governments from implementing large-scale support measures—particularly after the higher public debt left as a legacy of the pandemic (Canuto, 2021a).

The headwinds from the globally synchronous policy tightening would be compounded by a sharp deterioration of global financial conditions. Global GDP growth would decline by 1.9% in 2023 and 1% in 2024, compared to the figures of the baseline scenario. Those numbers are comparable to the 1982 recession, with growth slowing to 0.5%. Global GDP per capita would contract by 0.4%, in line with the 1991 recession, although milder than the 1982 episode when the population grew faster.

In any case, the evolution of global output under this scenario would be within historical experience of global recessions over the past five decades. Permanent output losses relative to pre-pandemic trends (Canuto, 2021b) would be greater if the ongoing global slowdown depicted in the soft-landing scenario turns into this third scenario.

Therefore, policymakers must take a narrow path. Monetary policy must be implemented at the intensity necessary to restore price stability, while fiscal policy must consider medium-term debt sustainability goals. Globally, policymakers need to stand ready to manage the potential spillovers from globally synchronous withdrawal of growth-supporting policies.

Ultimately, policymakers must cope with the dilemmas put before them as depicted in Phillips curves, whatever the configuration of parameters currently defining their shapes might be. Downward stickiness of inflation rates (demanding or not further monetary policy tightening) and the evolution of financial conditions (embedding various possible stress levels) will define which scenario the global economy will gravitate towards.

An important ‘known unknown’ is whether worsening financial conditions will trigger a financial shock by themselves, regardless of shapes of Phillips curves. According to reports from rating agencies and others, aggregate corporate and household measures of vulnerabilities currently do not show the levels of fragility seen in previous crisis moments. Many corporates have used the response of authorities to the pandemic via liquidity abundance and low long-term interest rates, as a window of opportunity to extend the duration at low cost of their liabilities.

However, there are those who point to areas of financial intermediation that have developed a high vulnerability to shocks – such as sudden disappearance of liquidity – in the recent past. Chapter 3 of the IMF’s October Global Financial Stability Report approaches how open-end funds, which offer daily redemptions while holding illiquid assets, have acquired a significant role in financial markets. They are vulnerable to investor runs and asset fire sales that can be triggered by sudden liquidity shocks, for instance (IMF, 2022).

As large banks ceased to act as market makers since the global financial crisis and the following voluntary and regulatory restrictions, being replaced by non-banking financial institutions that are obliged to liquefy assets upon demands from the funding side, sudden disappearance of liquidity has become more frequent and potentially more troublesome (Canuto, 2021d). Including in government bonds markets, as we saw in U.S. Treasuries in March 2020. Central banks are currently doing “quantitative tightening” and any U-turn on provision of liquidity to markets may signal a weakening of their drive against inflation.

Housing markets are also reeling from the elevation of mortgage rates. The long era of very low interest rates has also generated substantial overvaluation of assets relative to earnings (Canuto, 2021e). Private equity and venture capital funds have intensively bloomed.

As interest rates have entered the on-going upward phase, negative surprises may come from various spots. They may aggravate the macroeconomic downturn. The Phillips curve would then tend to exhibit higher unemployment rates (under-utilization of capacity), even as inflation rates move down.

References

Bezek, I. (2022). What Is The Dollar Index?, Seeking Alpha, August 18.

Brooks, R.; Fortun, J.; and Pingle, J. (2022). Global Macro Views: The COVID Inflation Shock is Over, IIF – Institute of International Finance, September 22.

Canuto, O. (2020). Why a Weaker Dollar Might Be Good for Emerging Markets?, Policy Center for the New South, December 22.

Canuto, O. (2021a). The Post-Pandemic Great Reset, Seeking Alpha, December 20.

Canuto, O. (2021b). Permanent Output Losses from the Pandemic, Policy Center for the New South, October 21.

Canuto, O. (2021c). Decarbonization and “Greenflation”, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB-51/21, December.

Canuto, O. (2021d). The Metamorphosis of Finance and Capital Flows to Emerging Market Economies, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB-24/21, November.

Canuto, O. (2021e). U.S. Bubble-Led Macroeconomics, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB-29/21, August.

Canuto, O. (2022a). Is the U.S. Economy in Recession?, Policy Center for the New South, August 2.

Canuto, O. (2022b). Whither China’s Economic Growth, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB – 53/22, August.

Canuto, O. (2022c). Emerging economies, global inflation, and growth deceleration, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB – 30/22, April.

Canuto, O. (2022d). Quantitative Tightening and Capital Flows to Emerging Markets, Policy Center for the New South, Policy Brief PB – 42/22, June 24.

Canuto, O. (2022e). Slowbalization, Newbalization, Not Deglobalization, Policy Center for the New South, June 1.

Canuto, O.; Aziz, A.A.; and Arbouch, M. (2022). Pandemic, War, and Global Value Chains, Jean Monnet Atlantic Network 2, September.

Denyer, W. (2022). The Key Drivers for Currencies, Gavekal Research, September 28 (www.gavekal.com).

Dritsaki, C. and Dritsaki, M. (2013). Phillips Curve Inflation and Unemployment: An Empirical Research for Greece, International Journal of Computational Economics and Econometrics, Vol. 3, Nos. ½, p. 27-42.

Gopinah, G. (2022). How Will the Pandemic and War Shape Future Monetary Policy?, International Monetary Fund, August 26

Guénette, J.D.; Kose, M.A.; and Sugawara, N. (2022). Is a Global Recession Imminent?, World Bank, September 15.

IMF – International Monetary Fund (2022). Asset Price Fragility in Times of Stress: The Role of Open-End Investment Funds, ch. 3 of Global Financial Stability Report, October.

OECD (2022). Paying the Price of War, OECD Economic Outlook, Interim Report September 2022.

Wolf, M. (2022). Why the strength of the dollar matters, Financial Times, September 27.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professor affiliate at UM6P, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil

[1] Consisting of the seven members of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and four of the remaining eleven U.S. Reserve Bank presidents; see https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomc.htm.

[2] The index’s components are the euro (58% weight), the Japanese yen (14%), the British pound (12%), the Canadian dollar (9%), the Swedish krona (4%), and the Swiss franc (4%) (Bezek, 2022).

[3] Signed on September 22, 1985, at the Plaza Hotel in New York City, between France, West Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, to depreciate the U.S. dollar by intervening in currency markets.

This Post Has 3 Comments

The “non-inflation accelerating rate of unemployment” (NAIRU) in this draft

should be the “non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment” (NAIRU).

True! Fixed. Thanks

The Youths Reliance Development Organization (YRDO) is a small non profit organization group of people with a zeal to resuscitating our society. Focusing on the most vulnerable group, the “YOUTHS” , who are in dear need, especially to difficult moment. We ask for assistance to caution these group. Thank you.

Comments are closed.