Policy Center for the New South, Seeking Alpha, Affluent Society, Capital Finance International, and TheStreet.com

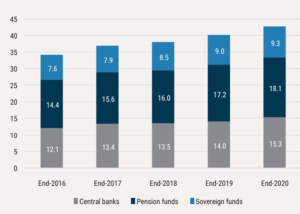

On July 21, the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum (OMFIF) published its eighth annual report on Global Public Investors (GPI). It included a survey the asset allocation plans of reserve managers of central banks, sovereign wealth funds, and public pension funds. Together, the 102 investors who responded to the survey manage $42.7 trillion in assets (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Total GPI assets by institution type, $tn

Source: OMFIF analysis (GPI 2021).

The survey highlighted notable changes in the composition of portfolios planned by global public investors. About 18% of respondents said they intend to reduce their holdings in euros over the next 12 to 24 months, while 20% said the same but with respect to the dollar.

Twenty years ago, the dollar represented 71% of reserve assets, whereas today it corresponds to 59%. The presence of the euro increased from 18% to 21% over the same period. Such changes have been smooth, progressive, and orderly over the past 20 years, noted Jean-Claude Trichet, former president of the European Central Bank, during the report’s launch.

One notable shift shown by the survey appears to be that the renminbi is set to become a more significant part of the global financial system as central banks add the Chinese currency to their reserve assets. About 30% of central banks plan to increase their allocations to renminbi in the next 12-24 months, compared with just 10% in last year’s report, while 70% said they intended to do it in the long term.

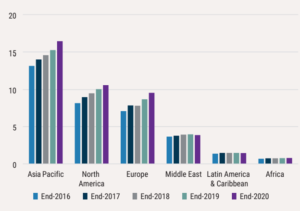

Central banks in all regions will be net buyers of Chinese bonds over the medium term. This is particularly the case in Africa, where nearly half of central banks plan to increase their reserves in renminbi. Asian assets in general are in high demand, with 40% of global public investors hoping to increase their exposure to the region (Figure 2).

Figure 2 – Total GPI assets by region, $tn, 2016-20

Source: OMFIF analysis (GPI 2021).

However, the starting point for the inclusion of the renminbi in the composition of reserve assets is still low, at only 2.5%, indicating that its inflection point as an international reserve currency remains somewhat distant.

In fact, in 2015, when the renminbi was incorporated into the currency basket that serves as the basis for Special Drawing Rights (SDR)—the accounting currency issued by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to be used among central banks—while China easily met the requirement of being among the world’s five largest exporters, its currency did not fully meet the requirement of being ‘freely usable’, for which it would need to be to be used widely for payments in international transactions and traded widely in major foreign exchange markets.

The expansion of commercial transactions, and increases in official reserves denominated in renminbi, the expansion of which was captured in the OMFIF report, have not yet been accompanied by an equivalent increase in transactions and in unofficial reserves with Chinese bonds. Also in the week the OMFIF report was published, the Institute of International Finance (IIF) published a separate report on the presence of the renminbi in international reserves, observed from purchases of Chinese bonds by non-residents, official or private.

According to the IIF, although Chinese government bond purchase flows have increased since last year, central banks accounted for a third of the total flow in 2020 and more than half in the first quarter of this year.

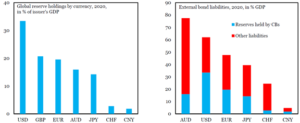

Total Chinese bonds held by foreigners are still small by the standards of emerging and developed economies. Despite the recent increases, Chinese external bond liabilities remain small relative to China’s GDP and its share of global trade (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Despite the recent increase in flows, foreign bond holdings are small in China.

Note: USD = U.S. dollar; GBP = pound sterling; EUR = euro; AUD = Australian dollar; JPY = Japanese yen; CHF = Swiss franc; CNY = Chinese renminbi.

Source: Lanau, S.; Ma, G.; and Feng, P. (2021). Economic Views – Reserve Holdings in Renminbi, Institute of International Finance, July 20.

Less than 3% of international payments are made in renminbi. Global reserves in renminbi are modest as a percentage of China’s GDP and relative to its international trade, especially when compared to well-established reserve currency issuers.

As Trichet said on the launch of the OMFIF report:

“The problem remains that the renminbi is not yet fully convertible. When the renminbi becomes fully convertible, I expect a big jump ahead. This is the view of Chinese friends, including the former governor of the central bank, Zhou Xiaochuan, who called for complete liberalization of the renminbi. That time will come. And when it comes, you will see the full realization [of what the OMFIF survey suggests].”

Given the size of China and the limited role of foreigners in local markets, it is safe to say that foreign acquisition of bonds and foreign reserves in renminbi could grow. However, it is best to avoid working with big, fast-rise scenarios. The U.S.-China relationship could remain tense and complex, possibly dampening the appetite of risk-averse reserve managers for renminbi bonds.

That said, the contribution of reserve accumulation to China’s bond flows could be large, even under conservative scenarios. If global reserves in renminbi increase from 1.8% to 3% of China’s GDP over the next decade, annual flows to the local bond market would consistently exceed $400 billion. If purchases by private investors remain stable, total foreign holdings in government bonds could reach 5% of GDP, not far from the median of emerging markets: 5.6% of GDP.

Commercial transactions and reserves of central banks and other global public investors could strengthen the position of the renminbi as an alternative to the dollar, euro, yen and pound sterling. But the qualitative leap towards the internationalization of the Chinese currency as a full reserve currency will only happen when confidence in its convertibility is sufficient to convince unofficial (private) investors to hold much more of their reserves in renminbi.

Otaviano Canuto, based in Washington, D.C, is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, a nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution, a professorial lecturer of international affairs at the Elliott School of International Affairs – George Washington University, and principal at Center for Macroeconomics and Development. He is a former vice-president and a former executive director at the World Bank, a former executive director at the International Monetary Fund and a former vice-president at the Inter-American Development Bank. He is also a former deputy minister for international affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance and a former professor of economics at University of São Paulo and University of Campinas, Brazil.

This Post Has 2 Comments

This article makes a simpler point than Prasad:

Prasad makes the point that you need critical mass plus reliable courts, etc.

Otaviano starts with, can you exchange It for other currencies? And that relates to the original, core mission of the IMF, which was to support stable exchange rates.

And, take that one step further: The need for stable exchange rates was to ensure inter-operability between different countries industries and resources. There were, before the war, British imperial trade preferences, there was an E European trade zone, and there was a Greater East Asia coprosperity sphere (Japan). Trade and stable exchange rates were meant to knit countries together, and to increase productivity by producing things where they could be produced most efficiently.

So, what if both Canuto and Prasad are wrong that China needs interoperability. If China is eventually willing to do business only with people willing to trade in renminbi, it’s possible that the world will have to live with two different systems. There will be global inefficiencies, but there are anyway because of externalities like climate change. The net effects of such existential externalities are far worse than the ineffiency of having two separate trade regimes in the world – a “western” one with dollars and euros and yen, and a “Chinese” one. Of course there will always be some porosity which mitigates the cost of separation, but it may turn out that neither convertibility nor legal institutions are necessary to China and its friends. They will play in their sandbox and we will play in ours.

I agree with your points, Matthew. Thanks for your comment

Comments are closed.