How Coronavirus Poses New Risks to Latin America’s Sputtering Economies

BY OTAVIANO CANUTO | FEBRUARY 20, 2020

The outbreak in China has already affected economic sectors in Latin America. Is there more to come?

China’s economy has come to a sudden stop. Large parts of the country remain in shutdown mode after the end of the Lunar New Year holiday, with national passenger traffic declining by 85% on the Wednesday after the break compared to 2019.

Outside of China, the impact of the slowdown has already been felt, with companies like Apple and Land Rover warning of lower production, as parts for their products simply fail to arrive on time. For Latin America, which counts China as its largest trade partner overall, the risks are also piling up.

There are four main channels through which the shock to China’s economy may be felt in Latin America. Here’s a detailed look at what the coronavirus might mean for the region:

Exports

China’s reduced economic activity could have a significant effect on Latin American exports. Except for Mexico, China is a major destination for products from Latin America’s largest economies, and is the number one trade partner for Brazil, Chile and Peru.

Primary sector goods and commodities comprise the bulk of the region’s Chinese sales. China purchases a hefty portion of the copper and other industrial metals produced by Chile and Peru. It is also the main buyer of soft commodities and agricultural and forestry products from Argentina and Brazil (as well as Chile and Peru), and a major consumer of Colombian and Ecuadorian oil and Brazilian iron ore.

While in general there has been a time lag between growth events in China and their impact on Latin American economies, the sudden stop nature of the current shock has led to immediate cancellations of transactions using force majeure clauses.

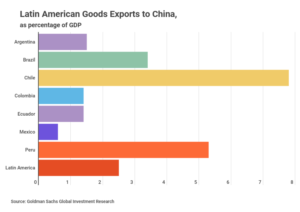

That said, there are limits to how the effect on exports will impact Latin American economies overall. According to Alberto Ramos of Goldman Sachs, although Latin American exposure to the Chinese market has risen significantly over the last two decades, exports to China as a share of GDP remain relatively modest for commodities exporters, at a regional average of 2.5%.

Imports

China’s shock may also transmit effects on the supply side, especially for Mexico and Brazil. The manufacturing sectors in both countries rely on parts and intermediate goods coming from Chinese suppliers. As global value chains have already been disrupted because of quarantines and mobility restrictions in and out of China, negative production effects are a real risk, as alternative sources cannot be tapped immediately. Both Samsung and Motorola have had to stop producing cellphones in Brazil due to the lack of parts purchased in China. Besides cellphone producers, car manufacturers, other electronics and appliances makers, and pharmaceutical companies could be forced to halt production.

Commodity prices

Commodity price shocks may also have a major impact on Latin American economies. China’s weight as a major consumer and importer of commodities worldwide makes it a key player in determining prices. Severe commodity price downfalls and a deterioration in terms of trade tend to have strong negative effects on income levels in Latin American commodity-dependent economies, though with significant differences among countries in the region.

Commodity prices declined substantially in the two weeks following the widespread acknowledgement of the coronavirus epidemic on Jan. 15, and recovered only partly as the situation was increasingly perceived to be under control at the beginning of February. Nonetheless, oil prices, as one example, have hovered at levels more than 15% below their Dec. 31 value.

Risk aversion

A fourth source of potential spillover in the region could come from heightened risk aversion on behalf of investors, and a worsening of global financial conditions overall. Investors fleeing risk means an increased search for safe assets — usually in developed economies — that can trigger liquidity droughts and strong exchange rate depreciations in Latin America. This is a pessimistic projection, and would only become a meaningful hypothesis if coronavirus-related events in China persist and inflict deep damage on the country’s economic dynamics. So far, markets have not attributed high probability to such a scenario.

All in all, economic spillover from the coronavirus outbreak in China can be expected to have a negative but modest impact on regional income growth in a year in which economic performance was already expected to be mediocre. The IMF has projected GDP growth in the region to stay around 1.6%, from an already weak position; economic growth in Latin America overall has been below 2% since 2013. Even excluding Venezuela, the 2014-2019 average growth rate was 0.9% per year.

The question now is to what extent the potential impacts of the coronavirus outbreak might lead to a downward review.

China’s return to economic normalcy will depend on unknown variables, such as when the peak in contagion occurs and when the virus’ spread is contained. In the meantime, quarantines and restrictions on mobility have already led to negative shocks on both the demand and supply sides. Household consumption has slumped, and many production processes have come to a halt. President Xi Jinping, meanwhile, has exhorted people to avoid “an oversimplified approach involving blanket closures or suspensions of business.”

The current dip in economic activity in China is expected to be partially offset by pent-up demand once normalcy resumes (though this is less the case when it comes to services). Macroeconomic policy is also expected to continue to cushion the blow, with initiatives beyond recent interest rate cuts and liquidity injections, including infrastructure spending and consumption-boosting measures. But the timing of the ascent after this decline will depend on when the outbreak can be considered over. In the meantime, more halted production lines and lower commodity prices will pose real risks for Latin America.

As summarized by John Lonski, Moody’s Chief Economist, the “coronavirus may be a black swan like no other,” a rare and unexpected event, with heavy potential impacts that are fully understandable only after they have occurred.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Canuto is a senior fellow at the Policy Center for the New South, principal at the Center for Macroeconomics and Development and a non-resident fellow at the Brookings Institute. He is a former vice president and executive director at the World Bank. Contact: ocanuto@cmacrodev.com

This Post Has 3 Comments

A good summary!

J’aurais aimé que l’auteur se penche, après le volet économique ainsi analysé, sur le volet religieux et scientifique d’une telle situation.

Thank you https://www.cmacrodev.com for informing us!

The world is having a hard time with this pandemic.

However, there is hope, a guide that will be useful: http://bit.ly/coronavirus-survival-guide

Good health to all!

Comments are closed.