The U.S. recession could hurt the South, particularly in oil and apparel exports, and Latin America and the Caribbean. But South-South trade is partly picking up the slack. Middle-income countries are driving export diversification of low-income countries. Developing countries may be moving toward a new version of export-led growth.

The Global Financial Crisis (GFC) has led to the sharpest trade contraction ever and the deepest since the Great Depression of the 1930s. Between 2007Q4 and 2009Q2, world merchandise imports fell by a whopping 36 percent. Al- though trade levels began a modest recovery in the 2009Q3, they are still far below pre-crisis highs.

Rapidly industrializing countries, such as China in the 1990s and 2000s and the “Asian tigers” before it, have relied heavily on overseas import demand—especially in developed countries—to fuel growth. But in light of the current need for global macroeconomic rebalancing, and in particular a durable contraction of U.S. final consumption, concerns have emerged about reliance on exports for recovery and growth.

How dependent are developing countries’ exports on demand in developed countries? This note shows that much of the recent growth in developing countries’ exports was driven by demand in other developing countries. This means that developing countries may continue to rely on South- South trade to recover from the crisis. In fact, countries like China are leading the recovery through strong import demand. Over the medium term, the development of an “export-led growth v2.0,” in which South-South trade plays a more important role, will be essential. Policy makers can support this process by continuing to liberalize South-South trade, focusing in particular on non-tariff measures.

The U.S. Recession Could Hurt the South, Particularly in Oil and Apparel Exports, and Latin America and the Caribbean . . .

Dependence on the United States as a destination for developing country exports varies considerably across countries and sectors. This point is important in light of the global trade collapse, since it suggests that impacts may differ consider- ably from one country to the next.

On a regional basis, low-income countries in Latin America and South Asia are the most dependent on high-income countries’ import demand. Mexico (an upper-middle-income country) and Central America rely heavily on U.S. final demand. The United States also plays a relatively important role in Sub-Saharan Africa’s exports due to its close relationship with Nigeria on oil and to preferences through AGOA (the African Growth and Opportunity Act that significantly enhances U.S. market access for 39 Sub-Saharan African countries). The European Union (EU), by contrast, is a relatively more important market for developing Europe and Central Asia, and the Middle East and North Africa based on geographical and historical ties.

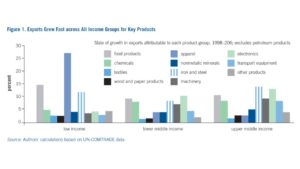

More generally, the United States and the EU-25 each absorbed about 20 percent of low-income countries’ export growth from 2000 to 2008. They absorbed 15 percent and 19 percent respectively of lower-middle-income countries’ export growth over the same period. It is important to keep these numbers in perspective, however. Of the 20 percent figure, nearly 10 percent comes from just one sector: petroleum products. Apparel accounts for an additional 4.3 per- cent, followed by other products (1.9 percent) and food (1.1 percent). Similar dynamics are present in the EU-25 data, with the exception of iron and steel imports (2.7 percent versus 0.4 percent in the United States). More generally, developing country export growth has been impressive, although with some sectoral differences according to income level (figure 1) (low-income, lower-middle income, and upper-middle income). All three income groups have seen strong growth in exports of food products, and iron and steel. The same is true for apparel in low-income countries, and for electronics in middle-income countries.

. . . But South-South Trade Is Partly Picking Up the Slack

Prior to the GFC, some proponents of the decoupling hypothesis argued that the risk of global contagion was relatively low due to different business cycles in the North and the major Southern economies. The idea was that a negative demand shock in the North could be ridden out thanks to demand in the South.

Recent experience has provided a reality check on these kinds of ideas. There is still great potential for demand shocks in the North to propagate globally via the trade channel. This is particularly true for a shock like the GFC, where output drops have been very strongly correlated across all major Northern markets.

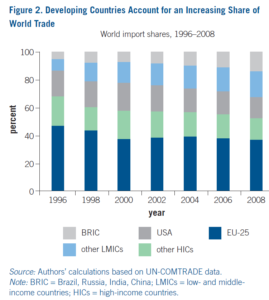

This picture is gradually changing. Northern markets, particularly the EU-25, are still important, but low- and middle- income countries are increasingly a source of import demand (figure 2). The BRIC countries (Brazil, Russia, India, and China) import share nearly doubled, from 9 percent to 17 percent, over the 1996–2008 period. Other low- and middle-income countries increased their share from 8 percent to 19 percent over the same time frame. In relative terms, the importance of the high-income countries as a direct source of import demand is decreasing, from a total share of 88 per- cent in 1996 to 69 percent in 2008. This dynamic remains true even though the numbers partly reflect derived demand from the North channeled through international production networks.

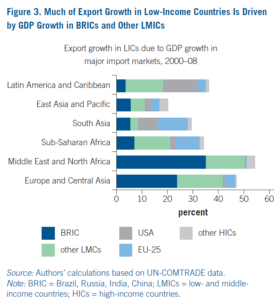

Rapid GDP growth is behind a significant proportion of the growing import demand in low- and middle-income countries, and particularly in the BRICs. A gravity model–based decomposition of trade growth shows that higher growth rates in low- and middle-income countries explain 51 percent of export growth in low-income Middle East and North Africa, 42 percent of export growth in low-income Europe and Central Asia, and 21 percent of export growth in low-income Sub-Saharan Africa (figure 3). All of these effects exceed the combined contribution of GDP growth in the United States and EU.

As GDP fell simultaneously in the North and the South during the GFC, the overall effect on final import demand could have been huge. However, this effect was greatly mitigated—and international trade supported—by effective stimulus packages in the major Southern economies. China has led the way on this front. China’s imports doubled be- tween January and September 2009, whereas the United States’ increased by less than one third (figure 4). The return to relatively rapid growth in Brazil, China, and India is clearly an encouraging development for the trading system, and could exert a significant stabilizing influence on the international

economy.

Middle-Income Countries Are Driving Export Diversification of Low-Income Countries

The GFC and trade collapse also need to be understood from a supply-side perspective. The world export share of low- and middle-income countries has been increasing more or less in line with their import share. For low-income countries, the bulk of this growth has been concentrated in a small number of labor- or resource-intensive sectors: petroleum products, food, and iron and steel. Together, these three sectors account for 76 percent of low-income countries’ export growth be- tween 1998 and 2006.

Developing countries’ exports have become more diversified over time, driven in part by changing South-South trade patterns. The export diversification index based on the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) of concentration shows an improvement of around 10 percent for low-income countries between 1997 and 2007. In absolute terms, this change is equivalent to exports moving from being spread evenly across four products to seven products. There is a tension between specialization—which is beneficial from a resource allocation perspective—and diversification that can have development and stability benefits. The optimal trade-off between the two is an important question for policy makers and researchers, but the evidence suggests that specialization does not dominate until countries are well into the high-income group.

China’s import pattern prior to the crisis reflects the way in which diversification is partly being driven by South-South trade: its share of capital equipment and consumption goods imports from the low- and middle-income countries nearly tripled between 2000 and 2008. An example of what is happening on a micro level is that low-income countries are increasingly filling the apparel niche previously occupied by middle-income countries; they are shifting away from raw textiles like cotton, towards simple manufactured clothing. Higher middle-income country demand for petroleum, iron, and steel is also helping low-income countries diversify away

from their traditional reliance on food exports to Northern markets (figure 5).

Thus, not only are low-income countries succeeding in exporting natural resources, but they are also moving into labor-intensive

manufacturing. One striking feature of the recent evolution of developing country exports is that the United States does not appear to be a central actor. Rather, income growth in middle-income countries appears to be a driving factor behind changes in the international pattern of specialization. If internally generated productivity advances are largely responsible for these income gains and a “growth trend decoupling” by LMICs is at play (Canuto 2009), concerns about weak consumption growth in the United States and other developed countries undermining the viability of export led development may be exaggerated.

Moving toward Export-Led Growth v2.0

China, the Asian tigers, and even post-war Japan pursued broadly similar approaches to export-led growth. Outward orientation was key, even though the precise degree of openness versus protection remains subject to debate. As the global economy stabilizes post-GFC, concerns have remained about limits to the extent to which other developing countries can pursue the same export-led growth strategies as before. One such concern questions the ability of the United States—where the GFC started—to remain a major import

market for developing countries. But as this Note has argued, there remains plenty of scope for leveraging international integration

as an engine of growth. Over the coming years, a new type of export-led growth strategy is likely to emerge.

What will the new export-led growth look like? It will surely pay greater attention to South-South trade than in the past. This rebalancing is only natural in light of the BRICs’ rise, and their increasingly important role as a source of import demand. It also reflects the likely macroeconomic re-balancing in the United States. However, this shift in demand patterns by no means signals a “sudden stop” to export-led growth. It has been taking place gradually over at least the last decade, and will probably intensify in coming years.1

Policy makers can facilitate South-South export-led growth. Protection rates in the South are generally high compared with those in the North. For instance, low-income countries face an overall level of protection of nearly 15 percent when they export to upper-middle-income countries, compared with 9 percent for high-income markets. South-South preferential tariff schemes—if fully implemented— would only be one part of the solution. Non-tariff measures account for nearly two thirds of the protection rate faced by low-income exporters to upper-middle-income markets. So from an export-led growth perspective, liberalizing non-tariff

measures should probably be a higher priority than extending tariff preferences.

Note

1. More reliance on South-South trade tends also to bring implications for the composition of foreign demand for developing countries. See Kaplinsky and Farooki (2010).

About the Authors

Otaviano Canuto is the Vice President and Head of the Poverty Reduction and Economic Management (PREM) Network, Mona Haddad is Sector Manager of the Trade Department (PREM), and Gordon Hanson is Director of Center on Pacific Economies in the School of International Relations and Pacific Studies at the University of California, San Diego.

References

Anderson, James E., and Eric van Wincoop. 2004. “Trade Costs.” Journal of Economic Literature 42 (3): 691–751.

Canuto, O. 2009. “Decoupling, Reverse Coupling and All That Jazz.” http://blogs.worldbank.org/growth, 09/01/2009. World Bank, Washing- ton, DC.

Feenstra, Robert C. 2004. Advanced International Trade. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Feenstra, Robert C., and Gordon H. Hanson. 2003. “Global Production and Inequality: A Survey of Trade and Wages.” In Handbook of International Trade, ed. E. Kwan Choi and James Harrigan, 146–185. Blackwell.

Hausmann, Ricardo, Jason Hwang, and Dani Rodrik. 2007. “What You Ex- port Matters.” Journal of Economic Growth 12 (1): 1–25.

Imbs, Jean, and Romain Wacziarg. 2003. “Stages of Diversification.” Ameri- can Economic Review 93 (1): 63–86.

Kaplinsky, R., and M. Farooki. 2010. “What Are the Implications for Global Value Chains when the Market Shifts from the North to the South?” Policy Research Working Paper 5205, World Bank, Washington, DC.

Leamer, Edward E. 1984. Sources of Comparative Advantage. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Rodrik, Dani. 2006. “What’s So Special about China’s Exports?” China & World Economy 14 (5): 1–19.

———. 2009. “Growth after the Crisis.” Mimeo, Harvard University.

Rose, Andrew K., and Mark M. Spiegel. 2009. “Cross-Country Causes and Consequences of the 2008 Crisis: International Linkages and American Exposure.” Working Paper No. 15358, NBER, Cambridge, MA.

First appeared as Economic Premise n.3, March 2010